September 1, 2010

I encourage "that clicking sound"

In a really good discussion of how technology has altered historical research David Turner writes

My only complaint, and I don't know if this is a complaint to be aimed at the camera manufacturers or the historians, is that I wish that there wasn't such a loud clicking sound when cameras take photos.

He's right that most digital camera users at the archives could eliminate that clicking sound. Digital compact cameras have the clicking sound merely to replicate the aural experience of a "real camera". Digital SLRs (and film SLRs, though how many people do archival photography with film?!) have to make that clicking sound. It's the sound of the shutter opening and closing to expose the sensor (or film) to light.

My most popular post on this blog has been Amateur Digitization for Historians, and I would now add one further variable to that discussion about digital compacts versus SLRs in the archives.

By way of background most archives don't allow flash (protecting the documents and protecting you from flash glare on glossy paper obscuring your images), and some archives don't allow copy stands, tripods and other stabilizing equipment. So a big concern in the archives is taking sharp photographs in low light holding your camera by hand.

Digital compacts typically use very high f-stop values which means your typical photo from a digital compact is sharper across the whole image with a wide depth of field. The foreground, center and background are all close to being in focus. But a high f-stop is not great in lower light (even room light), so many digital compact photos from archives without flash come out slightly blurry.

By contrast a digital SLR allows much lower f-stops than compacts. Now, with a lower f-stop your depth of field is reduced, but this doesn't matter as much in typical archival situations. Most parts of the paper are the same distance from the lens. SLRs also allow the user to set a very high ISO. This means you can compensate for the lack of light. Whereas a high ISO on film used to give you a very grainy image, digital SLRs give a much greater range of usable ISO values.

So, the short version of my advice is that if you can't use a stabilizing device, consider using an SLR for archival photography. You will lose many fewer photographs to being blurry than with a digital compact.

Another non-trivial advantage of the digital SLR is that it is much quicker. On a digital compact I find I can take about 400 photos an hour in the archives (mindlessly flipping from page to page). With a digital SLR I have taken over 1000 photos in an hour.

I think Turner's right that laptops, digital photography, and digitization of text are making fundamental changes to the practice of being an historian. My senior thesis advisor told me in the mid-1990s that how we do history hadn't changed much since Ranke or Beatrice and Sidney Webb (who wrote a great book about social and historical research). People looked at documents with their own eyes, and took notes. Then they analyzed and wrote about what they'd seen. Distance was a barrier to archival research. To be sure, the writing became quicker with the introduction of word processors in the 1980s, and computerized archival and library catalogs meant searching for sources was easier. But the process of primary historical research with old documents has been transformed in the last decade. Distance is less of a barrier to historical research, and the productivity of historians will increase tremendously as we take fuller advantage of the new technologies.

May 13, 2010

But now they can create a variable for overly_sensitive and dont_understand

This story is a doozy for academics (chronicle of higher ed version, sub required). Two business school professors sent a fake email to 6300 professors purporting to be from a prospective PhD student, with different versions of the email asking for an appointment now (today) or later (a week away). Different versions of the email also varied the apparent race and gender of the student.

Deception in the name of research. It's been done before and will be done again. A really important question is whether the impact on the deceived is outweighed by the scientific benefit of obtaining possibly better estimates of what people think and do. It's all very well for an historian to say "Involving colleagues, or any human beings, in a study without their knowledge and their prior consent is unethical," because historians rarely face this issue. Historians who use social science research so often delegate the dirty business of data collection to people long before us.

I happen to think that this kind of field experiment (it's not really survey research as some people think) is necessary. In the first instance there's the research done by sociologists and economists about racial and gender discrimination in housing and labor markets. You can't do this without deception, and there is to me a clear greater good in knowing the extent of discrimination in society.

But a more abstract and important question is how does measurement affect behavior? People say different things in surveys than they subconsciously reveal in laboratory experiments. But even in laboratory experiments people know they are being studied, and it's quite likely there's some kind of impact on their behavior in that setting. So field experiments where people don't know they're being studied, and might be [nearly] harmlessly manipulated are necessary to work out how people respond in different situations. Research involving deception has inherent risks, but that's a reason to monitor it closely and make sure the consequences for the deceived participants are low, not to never do it.

April 8, 2010

There was no golden age of original content

Interesting discussion at Crooked Timber about how much original reporting there is on the internet. Not much. Or maybe a lot. All depends what your prior expectations are, I suppose. There is certainly a lot of recycling of content, and probably there always was.

Now that we are lucky enough as historians to have access to lots of digitized text we can see the scale of this problem historical question more easily. A decade ago or more when I first got my hands dirty in original research, I used to think there might have been some golden age in the nineteenth century where newspapers and magazines had a high proportion of original content.

Why the nineteenth century? I suspect that publications with lots of original content are going to come in highly literate societies with printing presses, but despite that relatively limited communication to the outside world. Now, this does describe some significant parts of the world in the nineteenth century, Australia and New Zealand, parts of the American Midwest and West, and South America; the "regions of recent settlement" to quote an imprecise but known scholarly phrase.

But once you get cheaper transport, and then the telegraph, I suspect that the books and magazines of these regions are going to start reprinting material from elsewhere. And why not? The locals (recent in-migrants) wanted to know what was happening elsewhere, where they'd come from, where their friends and relatives had gone, and where they might move too. Indeed you have whole sections in nineteenth century newspapers labeled "News on the latest ship" or "News from the wires" (or something like that).

Not only that but the nineteenth century is full of books that are nothing but reprints of extracts from newspapers and magazines.

The other thing the digitization of magazines and newspapers has shown me is that it wasn't only news that was reprinted and not original (tho' it might have appeared original), it was, of course, also opinion pieces. The obvious successor to the political pamphlet was the newspaper column. Small town and city newspapers were particularly rife with this kind of reprinted stuff.

In short, reporters have long been rewriting someone else's copy and passing it off as new. I'd start with the hypothesis that this is an historical constant and not a decline in modern standards.

December 30, 2009

Technological fixes for terror

The response to the Northwest 253 attempted terrorist attack has been interesting. As after 9/11 and the Richard Reid shoe bombing attempts, one of the distinctively American response has been the reach for the technological response.

A common lament has been that if only there had been a body scanner or an explosive puffer, then Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab would not have gotten his flammable underpants onboard. Another lament, one I am more sympathetic to, is that if the data matching was better the existing screening system would have worked. After all, his name was in the big watchlist database, and then Abdulmutallab purchased a one way ticket with cash and showed up without any luggage. But again the lament is that technology will save us. Data matching is just another fallible technology. The fact that this suspect's names matched in some databases alerts us to one aspect of this case that could have been handled better with technology. But the next terrorist might have different names in different databases and elude easy matching. Americans seem to like technological fixes to their problems. In New Zealand the more common response to problems is that the government should do something, pass a law or establish an agency.

The response has also been interesting in that the technology and organization of suspicion that is encapsulated in screening airline passengers is pretty widely accepted by Americans. But the same logic that makes it OK to screen airline passengers also makes it OK to stop drivers to check for drugs or alcohol, install red light or speed cameras, or impose restrictions on gun use. But few of these interventions which would also save lives are politically acceptable in the United States.

December 21, 2009

A tutorial (discussion section) attendance policy that worked (for me)

Tutorials (discussion sections, but referred to as tutorials throughout because it's shorter) are an important part of university education. Done well, students come away knowing and understanding a topic. Also, students make friends in this form of class. This is a non-trivial benefit. Done badly, they are excruciating in their silence and stupidity, and make a Catholic mass seem short. I refer here to discussions in the humanities and social sciences rather than focused problem-set oriented classes in sciences. The format is often that students have read some documents, perhaps a whole book (at graduate level), or some articles or chapters at undergraduate level. Questions about the readings are posed, and discussion is meant to ensue. But that discussion doesn't always happen in practice.

Done well the students get a great deal of benefit from preparing for the tutorial, and then add to that with their peers' contributions and different perspectives. A large part of the success of a good tutorial comes from a critical mass of prepared students who show up. The question is how to motivate good preparation and high attendance, while also respecting that university students are young adults who can make their own good or bad choices about whether to show up or not.

There are many models for how to motivate preparation and attendance. But I was not satisfied with policies I'd used previously. For example, many of my colleagues in New Zealand have a policy of requiring attendance at 8/11 tutorials during a semester. Missing more than 3 tutorials means that students have not met "mandatory course requirements," and are not permitted to complete the class. It's not uncommon in American colleges for 5-20% of the class grade to be for "participation and attendance."

What I tried this year in my second year (sophomore) social history class was the following policy for motivating preparation and attendance. It worked well.

- There were 10 tutorial sessions in the (12 week) semester, and a final week of student presentations in lecture and tutorial time.

- Five of the 10 tutorials (labeled "starred" tutorials) and the week of presentations had penalties for non-attendance

- Attendance was recorded at the starred tutorials by students submitting at least half a page of notes on the week's readings (1-3 journal articles or chapters, 30-60 pages of reading)

- Non-attendance was penalized with the following deductions from the final mark

- 1st missed tutorial/presentation: 4%

- 2nd missed tutorial/presentation: 8%

- 3rd missed tutorial/presentation: 16%

- 4th missed tutorial/presentation: 32% (highly likely fail)

- 5th and subsequent missed tutorial/presentation: 64% (definite fail)

- Students were encouraged to be responsible about letting me know if they could not make a tutorial for a legitimate reason (sickness, other university event clashing), and that if they handed in their notes they would not have marks deducted.

It looks way more complicated than it really was. Since it was a policy that differed from the standard ones in our department (and cognate departments in the humanities and social sciences) there were some questions about it. But the students understood it without any problems.

With this policy, 27 of a class of 31 did not lose any marks. In other words, 90% of the class attended (or demonstrated their preparation if sick or otherwise legitimately absent) for all the tutorials they were responsible for coming to. One student lost 4% and another 8%. Two students failed after missing 4 tutorials.

So, the policy had a very beneficial impact on student attendance. Most students prepared for class by taking more notes than required, and class discussions went very well as a result.

The policy seemed to work well for the following inter-related reasons

- I eliminated the common "mandatory course requirement" of (x-3) out of x tutorials that just permits absences from 3 tutorials. These absences are often concentrated around the deadlines for other classes, and especially at the end of semester. Students are busy and they reasonably prioritize things that are graded, or are fun. Wishing they loved learning more, and exhorting them to do so, just leads to disappointment.

- The sharp break in the "mandatory course requirements" approach between the penalties for missing 3 and missing 4 tutorials is unfair, and not well designed to motivate consistent preparation and attendance.

- The severe level of the penalties for frequent absences got students' attention, as it meant failing

- The policy did not require me to grade participation per se. The burden on me in implementing the scheme was minimal (less than 5 minutes per class to scan the notes that were submitted and record who didn't submit notes).

- A realistically small level of notes submitted for attendance (half page) was meant to achieve two goals

- It was meant to be, and was, seen as a realistic amount for students to achieve.

- I also encouraged the students to try and be concise in their note-taking, developing the skills of summarizing an article in a few lines -- that sometimes less is better for them. It was much nicer being able to tell students that they had somewhat over-prepared and discuss how they could do less work (but more effective!) next time.

- I did not try to compel perfect attendance, but designated some tutorials as more important than others. 6 weeks in which attendance was rewarded seemed to strike the right balance between encouraging work on this class, and recognizing that there can't be something due every week. The "starred" tutorials were mostly in alternating weeks.

- In the alternate weeks I ran practical workshops to help students with their research for the class. These were sometimes structured (worksheets on various aspects of the research), and sometimes an open computer lab. Clearly, not every class would need computer labs. The general idea was to do a more practical session where the success of the session did not rely as much on student preparation or attendance.

- In practice (this being the winter of the swine flu) I was understanding of student absences, when notes were submitted. Students seemed to view the policy as reasonable. The policy did the work of motivating students to prepare. I did not have to exhort students to do the reading and prepare for class because there was an objective penalty for not doing it. This freed up my emotional energy for more important things in the class.

The policy seemed to have a positive effect on classroom relationships, as well as motivating preparation and attendance. The awful tutorials where people attend without having done the reading, and the discussion proceeds slowly until the instructor realizes students haven't done the reading. The instructor then gets cranky at the students for not preparing for the class, and the relationship between students and instructor suffers.

All in all this was a low-workload way of motivating student preparation and attendance, and it seemed to improve student outcomes. By making the penalties for not preparing and attending explicit I respected students' abilities to make their own decisions about their time. Attendance was not compulsory, but it was valued.

By penalizing non-attendance and preparation rather than grading participation and attendance I did not have to grade students' contributions to discussion. This meant the discussion atmosphere was relaxed, because students who attended had prepared, but knew they weren't being evaluated for what they said and did once in class.

The details of the policy would vary in other classes, but the key features I would replicate are

- Preparation and attendance at about half the tutorials was valued

- Other tutorials were less dependent on student preparation/attendance

- Attendance was measured by a reasonable amount of non-graded work that nearly every student was able to regularly exceed

- Penalties for non-preparation and attendance were small at first 'miss', but increasing.

Finally, I must gratefully acknowledge my colleague, Alexander Maxwell, who suggested aspects of this to me, but disagrees with some of my adaptations.

April 11, 2009

Easter absurdities

New Zealand's laws about opening stores on Easter are more than a little silly. As the New Zealand Herald summarizes it:

Currently the law bans all but a few retailers such as service stations, cafes and dairies from trading on Easter Sunday.Some tourist destinations in Queenstown and Taupo are also exempt.

Last year dozens of shops ignored the ban, many choosing to pay a $1000 fine in order to keep the doors open.

While New Zealand has no state religion, here we have a law that restricts trading on a religious holiday. I think it might be a legitimate state interest to restrict stores opening on days of genuine national significance like Waitangi Day and ANZAC Day, but Easter? Why should we compel people to recognize a religious holiday?

But the absurdity as always is in the exceptions. It's OK for supermarkets in tourist areas like Queenstown and Taupo to open, but not for supermarkets in "residential" areas to open. Quite what the animating principle behind this distinction is, I don't know. Public and religious holidays are important, but not when there's money to be made off tourists. Every principle has its price. Back in the olden days (1943 - 1977) when hardly any stores were open in New Zealand on the weekends similar absurdities sprung up. New Brighton near Christchurch and Paraparaumu near Wellington were defined—for the purposes of regulating store opening hours—to be outside Christchurch and Wellington because they were beach destinations. So, it was OK for shop assistants in those towns to work on the weekends but not elsewhere.

The Herald also reports that one proposed resolution to this situation is to take New Zealand back to another historical absurdity: the local referendum on store opening hours: "The most recent bill, drafted by Rotorua MP Todd McClay to be introduced to parliament's ballot, calls for a law change allowing local communities to decide whether shops would open."

This was the early twentieth century way of dealing with the problem in New Zealand. Every town, from the cities like Auckland and Wellington to the smallest town with just a few stores, had a referendum on whether stores would open on Wednesday afternoon or Saturday afternoon. The day stores were closed was known as the "half-holiday." The referendum had the appeal of being democratic, of letting the citizens and consumers determine when stores would open, but it had the classic problem of democracy: minority groups were compelled to accept the wishes of majorities. The store that wished to open on Wednesdays was instead made to open on Saturday, when the community might have benefited from having some open one day, and others open the other day.

The cost and internal contradictions of such a system were obvious by the 1930s, and the Labour government's response was instead to regulate in 1944 that virtually no stores be open on the weekend. When the National government liberalised the law somewhat in the 1950s it introduced a byzantine list of what was acceptable to sell on the weekend, necessities being OK and luxuries having to wait until 9am on Monday. A cottage industry in lockable covers to put over the "luxuries" (like magazines) during the weekend developed. The moral principle of restricting store hours had been whittled away. Why it was OK to sell milk but not magazines was not clear.

A similar absurdity is present with the Easter trading laws. Why it's OK to have smaller grocery stores open in every city, and the larger ones in some places but not in others, is not at all clear. The only clear principle is that everything closes by diktat or store owners get to make up their own minds. I suspect that many would choose to close, in the same way that few non-grocery/liquor/pharmacy stores in New Zealand take up their freedom to be open at 9.30pm at night.

January 15, 2009

History on the south side

Last semester I taught a social history course that centred round students doing primary research with the 1924 Houghteling survey of 477 Chicago families. One of the students did a very interesting essay that mapped the distance to work of two groups of employees. Using the file of addresses that he had compiled I then set out to see some of the houses, and whether they still remained. Most of these houses are on the south side of Chicago, where there has been a bit of urban change in the last 80 years.

Setting out with a map and camera I had a list of 40 houses. I did this historical research on foot. To this degree I was being faithful to the original investigators who certainly walked around the Chicago neighborhoods collecting the surveys. With 40 houses to cover I ran. If you are familiar with the south side of Chicago you will appreciate that a white guy running around with a piece of paper and a camera taking photos of people's houses might attract attention. However, I only had one person ask me what I was doing. He was bemused by the explanation that I was an historian. I guess that's what the Chicago Police Department now call undercover agents -- historians. Covering 21 miles (2:50 running, 4:00 total out there) I only got to 31 houses. About half of them were probably the original 1924 house. The results are summarized in the table below for those who are interested.

The diversity of the transformation was interesting. Some of the houses had been replaced by UIC. Others had been replaced by gentrification, particularly in the Bucktown area. Yet others, particularly near UIC and around 18th - 21th St were now largely Hispanic neighborhoods, perhaps today's unskilled immigrant laborers*

This was a particularly fulfilling intersection of running, research and teaching. With the addresses of all 477 families computerized I could envisage a student project to map the transformation of all of these houses. This would even be possible from New Zealand with Google's Street View. But such a project would hearken back to an earlier era of social science which studied neighborhoods as things in themselves. Modern social scientist might perhaps declaim that study of the neighborhood as superseded by a methodological focus on the individual and family in different contexts. So, there goes the neighborhood.

You can see a picture of the transformation here: www.evanroberts.net/chicago_houses

* I hasten to add that I am not implying Hispanics to be unskilled laborers, but am echoing the title of the original research.

| House is now | Total |

| Presumed to be 1924 house | 16 |

| Newer construction, sympathetic style | 2 |

| replaced by industrial buildings | 2 |

| apartment building | 1 |

| Church parking lot | 1 |

| Newer construction, since abandoned | 1 |

| Parking lot for Howard-Orloff Jaguar Volvo car dealer and on-ramp for I-90/94 | 1 |

| Presumed to be 1924 house, but front unit probably knocked down | 1 |

| Presumed to be 1924 house, but front unit probably knocked down? Original survey doesn't mention front units | 1 |

| Public housing units | 1 |

| replaced by commercial buildings | 1 |

| school(?) and park | 1 |

| UIC Environmental Safety Facility | 1 |

| UIC Parking lot for Eye & Ear Infirmary | 1 |

| (blank) | |

| Grand Total | 31 |

December 21, 2008

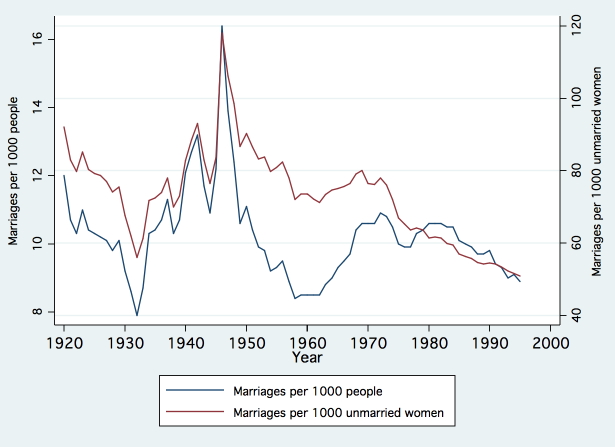

Marriage is not recession proof, let alone weddings

As the financial condition of the country worsens, the wedding industry, so long considered recession-proof, is seeing fairy-tale weddings stripped of their sprites, their sparkle and everything else that suggests splurge. (from the New York Times, "Recession? Time to Slash the Flower Budget"

This puzzled me. Last time we had a long and severe depression marriages plummeted, as you can see from the figure below. Perhaps the current recession will be different. We are starting from income levels significantly above those of 1929. The magnitude of people's reactions to the current recession will be different than in 1929, though the direction may be similar. There is now, as the same NYT article, suggests greater policy support for marriage with tax and health insurance arrangements prodding people into formalizing relationships that might otherwise just be people living together.

Source: Historical Statistics of the United States, Tables AE507-508.

August 19, 2008

But the hemp industry wasn't very large in South Carolina ...

A little historical humor. For what it's worth I gave this one the point it deserved.

December 21, 2007

Shooting rats, hitting people

How common was shooting at rats but hitting a person in early twentieth century America?

I pose this question because twice in the last couple of weeks I've come across small-town-newspaper stories from the early twentieth century Midwest that report on people shooting rats—trying to shoot rats might be a better description of activities—missing, and hitting a person. I haven't gone looking for these stories, I've just happened upon them while looking for stories about a [New Zealand] Maori entertainer in small-town America in the 1910s and 1920s. Maybe I got lucky, and I happened upon the couple of rare instances of "man shoots at rat, hits person" stories that ever appeared. But I suspect not. A cursory search on Newspaper Archive brings up more similar stories. Do a similar Google News search today and you don't get anything.

To my modern eyes these stories appear tragicomic, and a little absurd. But historians can't merely laugh at the past, they have to explain it. Why did people get hit by stray bullets aimed at rats? A plausible explanation would include the following elements

- There really were more rats around the city in the late 19th and early 20th century. Cities were dirtier.

- People were more inclined to shoot rats rather than trap them. Other articles about the sorry perpetrators of these shootings mentioned that hordes of rats undeterred by traps drove people to shoot them.

- When there's no-one around to contradict your claim, what a convenient excuse for an accidental shooting!

- What a great story for the newspaper! I suspect the tragicomic appeal of the story was not lost on the editors of small town papers competing for readers.

Merry Christmas, and don't get shot by the rat catcher!

August 23, 2007

The AHA's muddled approach to classifying research

The American Historical Association (AHA) has a confused way of classifying its members' research interests. That confusion causes members some consternation when the AHA then proposes to eliminate certain categories.

The root of the confusion is that the AHA's taxonomy attempts to fit several dimensions of historical research into a one-dimensional list. The AHA claims that since members "can select up to three categories that interest them," a category that lacks support from at least five members must "lack a significant constituency" in the membership. Last year the AHA tried to eliminate "psychohistory," this year they propose to potentially eliminate various periods of Japanese history, New Zealand history, Sudanese history, and British Columbia because fewer than five members listed these categories as a research interest. In response I've gone and changed my membership profile to now include New Zealand history, perhaps to save it from the chopping block.

Apparently, some of the reasoning behind eliminating categories is to save space on the printed form that members fill out to indicate their research interests. In the age of the Internet it scarcely seems necessary to have printing technology dictate intellectual decisions about classifying the areas of historical research. A favorite rhetorical trick of historians is to say "What if your students said that?" Well, what if your students used similar logic? This is the AHA saying that it is revising intellectual distinctions because it ran out of notepaper. What if your students said that?

The AHA is at pains to point out that categories can be added back into the taxonomy of research interests, if enough members request it. This is hardly the way to organize a classification system. To be meaningful a classification system should be stable over time, not subject to the whims of membership votes. If a category is significant as a field of study it should be left in the taxonomy, so that if and when it re-emerges with more support that change can be accurately tracked.

The biggest confusion in the AHA's research taxonomy is its approach to combining geographical, chronological and topical classificiations into one dimension. A basic principle of classification is that you should not combine separate aspects into one. Take my own research, for example. A compact description of what I do is economic and business history of New Zealand and the United States between [about] 1860 and 1960. I think I have a relatively coherent research agenda, but the AHA's muddled research taxonomy doesn't allow me to adequately describe it in the three categories I'm allowed to choose.

How the AHA comes up with its categories I don't know. Under United States history you're allowed to choose various time periods, including in the modern era "1877-1920," and "since 1920." Every time I see this it mystifies me. I understand that 1877 is significant as the end of Reconstruction, but that surely privileges a particular master narrative of American history over any alternatives. And "since 1920"? You can make any sort of argument you like for the significance of 1920, but 1930 is pretty significant too, as well as 1932, and 1912, and well, you get the idea ...

The AHA should revise its research taxonomy entirely. It should allow members to separately

- Select several countries they are interested in. If countries have important sub-national divisions, either historic or contemporary, they can be selected too. At present the AHA's categories for Canadian research are a mystery as well. You can select British Columbia or Québec as separate subjects, but Ontario must fall under the generic "Prairie Provinces." I know only a little about Canadian history (it's glorious!) but Ontario is a little different than Manitoba, principally on account of the city of Toronto and its environs.

- Select the time period they are interested in. This could be specified as a starting year and ending year. It would then be trivial for analysis to combine similar years into categories and centuries for tabulation. More interesting information on the overlap in research time would result from this approach rather than the rigidly specified "1877-1920" approach taken at the moment.

- Select several topical approaches they are interested in. The present list of topics is an alphabetically ordered soup of themes and methods. Comparative, economic and psychohistory are arguably methods, mixed in with themes or topics like labor, immigration, and the mysterious "General Studies". The latter is about three times more popular than New Zealand history, for what it's worth.

The AHA might reasonably respond that this would lead to an explosion of information. It is not clear whether the AHA's membership taxonomy is meant to be a survey of the core topics its members are prioritizing in their research right now, or a broad survey of the wider field members set their research in. The way it's set up at present you have to choose between different levels of specification. For example, say you're a Canadian historian and you're presently working on a topic in British Columbia. Which do you choose? The obvious answer would be both, with the choice being presented as the hierarchy of precision that it is. The current system forces a trade-off between narrow and broad visions of research without indicating what the system is designed to elicit.

The geographic and chronological categories reflect this confusion. Take those U.S. history time periods again. Why the 43 years between 1877 and 1920 deserve their own category while the modern era (87 years and counting) and the colonial period (about 200 years) are implicitly all of the same is not clear. Within these eras, few people are likely to be doing research on the whole period specified by the AHA. It can't possibly be a fair representation of what people are doing. If your research spans several of these artificial eras, what are you meant to do? My dissertation dealt with the period from 1850 to 1940. I could use all three of my apparently generous allocation of category choices to describe only my time period. If you do American Indian history your chronological divisions are Pre-contact, Colonial, 19th century, and 20th century. Perhaps there's a long 19th century concept in here that covers the 1776-1800 period, but that's not stated. And why does American Indian history work in neat centuries while the rest of American history pivots on wars and presidential elections?

Similar absurdities in chronological specificity are apparently present in the Asian history section. In the Chinese history section if you study Taiwan you're explicitly constrained to doing it after 1949, but if you study Hong Kong and Macao there's no time period. I can sort of divine the reasoning here, but it's not really clear. Moreover, "and"? What if you only studied one of Hong Kong or Macao?

The same error appears where "Australasia and Oceania" are specified as options. I appreciate the AHA specifying New Zealand as a separate option, but in case they don't know Australasia implies Australia and New Zealand. As it stands, it's the Australian historians who could complain they're not fairly represented. Moreover, while many historians of the Pacific islands (Oceania) have to consider Australasia, the converse is not true. Most Australian and New Zealand historians work in blissful ignorance of the Pacific islands, the islands being merely convenient transit points on the way to San Francisco or Vancouver by boat or telegraph. You could also be an historian of Oceania's interaction with the United States or other Pacific Rim countries without studying Australasia much, if at all. Lumping Oceania in with Australia and New Zealand misrepresents that field too.

In short, the taxonomy is a mess. It would be better to start over than keep building on the existing foundations.

August 16, 2007

A short history of hill repeats

Arthur Lydiard is indelibly associated with the history of long distance running in New Zealand. It's a history of great achievements in the 1960s, lack of official recognition in the 1970s, and growing appreciation for Lydiard's achievements in the last two decades. It has been interesting for me to watch a talented guy in Arizona work through Lydiard's schedules, including hill repeats, faithful to the schedules Lydiard drew up in Auckland and beyond.

Arthur Lydiard is indelibly associated with the history of long distance running in New Zealand. It's a history of great achievements in the 1960s, lack of official recognition in the 1970s, and growing appreciation for Lydiard's achievements in the last two decades. It has been interesting for me to watch a talented guy in Arizona work through Lydiard's schedules, including hill repeats, faithful to the schedules Lydiard drew up in Auckland and beyond.

Although Lydiard is associated with New Zealand, within the country he is associated with Auckland running. Hill repeats are a good example of the association with Auckland. Around the country, the influence of Lydiard on New Zealand running is clear, though "the schedules" have been modified by succeeding generations of coaches who have been dissatisfied with the periodization or other aspects. I could not claim that no one in Wellington does hill repeats, or that no one ever has, but I will claim that there's a strong tradition in Wellington running that disregards hill repeats for the long or hard run "over the hills".

Lydiard's hill repeats are not a general theory of the best way to train, but a specific adaptation to the local environment. Compared to Wellington, Auckland has lower, fewer, and flatter hills. You really have to work hard to avoid the hills in Wellington, and you can design a relatively long run with regular steep climbs and steps that gives you all the benefits of the hill repeats with none of the structure. You come to a hill, you run up it hard. You come to a set of 200-500 steps. You run up them. As my high school coach used to say, "you can shuffle uphill, but if you shuffle up steps you'll break your legs." If you think hills are good for your leg strength, steps are even better. Taking them one at a time teaches quick movement, while bounding up two or more at a time builds power in your push off. If you have a flat stretch you might stride out a bit, but save something for the hills to come. You could plausibly do 20 miles or more in this fashion in Wellington. This is much less possible in Auckland. The hill repeats were the way to get in lots of hills in that environment.

The Wellingtonian attitude to hills is in no way a disdain for the idea that hills are really good for you. The disdain is for the idea that you need a formal structure to running on hills. When you live in a place where 300m of vertical gain in an hour's recovery run is normal you really don't to run hill repeats.

July 1, 2007

Do they?

This is a fortune, but in reality I think that's an open question ...

June 14, 2007

A short jaunt past history

This entry represents the confluence of two of my favorite things: running on trails and history. Meeker Island lock and dam was the first set of locks constructed on the upper Mississippi river in 1907. If you are strolling or running along the east bank of the river just where Minneapolis meets Saint Paul it has always been possible to go down some steps (in Minneapolis) or down a rutted little trail (in Saint Paul) to the riverbank and see the remnants of the dam. When the river level is low you can see a lot of what was there, if not the island itself which is submerged by the now much deeper channel of the river.

The lock and dam lasted just five years, and was then submerged by the raising of the river achieved with the construction of the much larger dam at the Ford Parkway.

Now with the centenary of the Meeker Island dam upon us, the Saint Paul city council has spruced up the area a little, added some tables and benches, and made the path alongside the river more runnable (or walkable). The best way to see this on a run is to run down the wagon road on the Saint Paul side, along the river, and then up some iron steps (beside a storm water outlet) into Minneapolis to emerge about 100 meters from where you went down the wagon road.

Lake St bridge

Minneapolis' beach on the Mississippi

Links

Wikipedia

National Parks Service book on the history of the Mississippi in the Twin Cities

June 8, 2007

My work here is done

This entry got delayed and delayed because I had so many different ideas in my head about how to write it. That feels a bit like a metaphor for the whole dissertation ... I also hesitated over the title [of this entry]. Strictly speaking my work here is only very nearly done, as I have a few trivial footnotes to revise, forms to submit, and Graduate School bureaucracy to wait for, before the degree is conferred. That's a metaphor for life and history itself. Few things have clear endings.

All that is prelude to saying that last Friday I successfully defended my dissertation. The title is "Her real sphere? Married women's labor force participation in the United States, 1860-1940". If you really want to know more ... you can easily contact me.

It's a good feeling to be done. The best metaphor for what the defense was like, was that it was like a moderately long race. The defense lasted about 1 hour and 40 minutes, and once I'd settled into the ebb and flow of the discussion it was good. I was tired afterwards—like you would be after racing for that long—but I didn't feel totally wiped out by it. All the advice I've gotten suggests that I should put the dissertation topic aside for a few months before returning to any research on it. In that way, defending your dissertation is like a marathon. You've got to forget about it before you return to it. Except that few people try and defend a dissertation in all fifty states. (I've heard of people with two PhDs, or a PhD and a MD. Not common, but not unheard of. My grandfather told me, erroneously I just now learn, that Albert Schweitzer had four doctoral degrees. The always reliable internet tells me that Schweitzer was merely accomplished in theology, music, philosophy, and medicine. His doctorate and M.D. appear to be his only academic qualifications.)

It will be easy to take a break from studying millions of dead men's wives, because on 1 July I take up my new job as a Lecturer (equivalent to Assistant Professor in the North American academic system) in New Zealand and United States history at Victoria University of Wellington. This will not be news to some readers of this blog who I know in "real life," and will be news to others.

Hopefully time will allow me to maintain some blogging. That, after all, is the advantage of the magic internet. It's everywhere, even in New Zealand ... But who knows? In the last six months as I finished the dissertation it should have been obvious to regular readers that my intellectual energies were elsewhere. This blog has always been a eclectic mix of the personal, professional and political ... and I hope to keep it that way. The proportions of that mix are not fixed over time.

Academic readers may be curious to know whether the blog had any effect on my job search. If you go by the measure that I got the job, obviously not. I made no effort to highlight or hide the blog while I was applying for jobs. It's always been a useful discipline for me to imagine that people might read this while googling about my job application. If they exclude me on the basis of what I've written here, so be it. The blog is a good predictor of the kind of conservation you might have with me at morning or afternoon tea.

And on that note, time for an early morning cup of coffee ...

May 29, 2007

Military history and other subfields

Memorial Day brought with it the opportunity for some people to lament the apparent passing of military history from the nation's universities. I'm sympathetic to the argument that military history is an important field, possibly somewhat neglected, but I don't believe there's any great conspiracy to chase military history out of history. Academia just doesn't work like that.

Change the nouns in those articles, and you have a template for complaining about the decline of "X history," and "Y economics," and "Z sociology." Military historians are hardly the only people to feel themselves on the outs. Indeed, please show me the sub-field anywhere that feels it is making out at the expense of all the others. Few academics feel that way. It's hardly motivating to feel you've conquered the academic world, and answered all the questions. Every academic needs to feel a little insecurity about the value of what they're studying. It keeps you on your toes. In the lab, archives, or library it's easy to convince yourself that what you're doing is self-evidently important. It isn't.

The rise and fall of topical interests in academia is chaotic rather than conspiratorial. People are rewarded for doing new and different scholarship. Inevitably that leads to golden ages followed by declines. Or, if you like, periods of excess in one direction, followed by corrections. Booms and busts. The military historians have a lot on their side for a resurgence. War has been a significant part of human history by any measure. It has changed the borders of nations, killed people, uprooted millions of men and women from their normal jobs and put them in the service of their country, brought down political leaders, and led to the rise of others. Significantly, war is often quite well documented, leaving much material for the later historian. People will return to military history because there really is something there to study, and precisely because there are fewer people doing it now.

Looking at faculty lists is a terrible single indicator of what anybody is studying now. The faculty at elite institutions represent what was happening in history at best a few years ago when the most recent hire selected a dissertation topic, and on average perhaps 15-20 years ago (a reasonable guess at median time since PhD graduation for all faculty in elite departments). Faculty webpages do not list what people are becoming interested in -- they represent conservative, historical information on what someone has done. Dissertations, conference papers and articles are a better leading indicator of what's going to be significant soon, though harder to compile and evaluate. 15-20 years ago history was in the middle of the "cultural turn." I'm glad that historians have learned that "language matters," but some of the excess along the way was not to my intellectual tastes. The new enthusiasm in history for transnational history shows its origins in cultural history. Basically, some transnational history is about how the same "texts" were read in different ways in different places. But once you start asking that question, you end up asking about how the places, people and events differed to give those different readings. You're not quite through the looking glass, but you're getting back to bigger questions than the intense analysis of obscure texts can support.

If transnational history can't open the door for a revival of military history, I'm not sure what will. It won't be the same military history that we had in the past, but nothing is ever the same the second time around. It might even be better after decades of intellectual marination. Take, for example, the economic history of institutions or business history. I cite these examples because I (sort of) know them. Back in the day (that would be the first half of the twentieth century) economic history was nearly entirely contiguous with the history of state institutions and policies, and the history of businesses, often the history of specific firms. With new ways to analyze old data, economic history in the second half of the twentieth century was (and I generalize broadly) concerned with questions that could be answered with microdata, and the macroeconomic question of what drives economic growth. But now lo and behold, there's renewed interest in business history and state policies and institutions. It looks quite different than it did 50 years ago.

A revived military history will not be about battles we already know about. It's been done. No one gets rewarded for literally reinventing the wheel. They get rewarded for finding new uses for old wheels, and marketing old wheels as new. Things change in 50 years. You can't go back, but you can take it with you.

May 25, 2007

Advertising you don't see today

I found this advertisement in a 1937 issue of Fortune magazine. It's revealing, to say the least. Fortune was regarded as a relatively "progressive" business magazine, and before World War II had a staff of excellent journalists and photographers.

Among the interesting aspects of the advertisement is the black man working as a servant. The vast majority of black domestic service workers in the 1930s were women. Butlers—which this man appears to be—were not as common in the United States as in Britain. It's doubly interesting that this advertisement portrays having a black butler as part of a desirable lifestyle.

April 13, 2007

Watch your denominators!

Interracial marriage is apparently on the rise—they're surging according to the New York Times, which makes me wonder how soon if ever it will be until the word "surge" gains an unfortunate connotation from the success or otherwise of the "surge" in Iraq, but I digress—.

My one quibble, and multiple questions, about this new trend relate to the near complete absence (at least in the article) of any context for some of the numbers. We learn, for example, that in 1970 there were 65,000 inter-racial marriages and 422,000 in 2005. That's all very well, but how many marriages were there in total? A quick trip over to the National Center for Health Statistics (who actually keep the data) shows there were 2,230,000 marriages in 2005. That's a pretty impressive flow of inter-racial marriages into the stock of marriages, on the order of about 1 in 4. Certainly it captures the trend better than the 7% of existing marriages being inter-racial.

Perhaps this is all covered in the book, but rates of inter-marriage are in part artifacts of the proportion of the population that are different races. Say you have 90% of the population white and 10% black (this is a reasonable approximation of the American population from 1870 to 1990), even if you assume marriage is totally random with respect to race, you're not going to get a very high rate of inter-racial marriage. Change the way you enumerate race in 2000 and you'll get a rapid increase in the number of non-white people, and a significantly greater chance that white people will end up married to non-white people (simply because white people are 75% of the population, a random inter-racial marriage will more often be a white person married to a non-white person than two different non-white races).

In other words, some of the increase in inter-racial marriage is probably algebraic rather than attitudinal.

March 26, 2007

March 14, 2007

A desecration on the landscape

I think this blurb was meant to read "The Industrial Revolution has sometimes been regarded as a catastrophe ..." Otherwise, that's one very influential and damaging book.

(from the latest Oxford University Press catalog)

March 1, 2007

Anthony Trollope on Wellington

Plus c'est la meme chose, plus ça change. Trollope wrote in 1874.

February 21, 2007

But would you want your daughter to marry then?

Recently the New York Times ran a story about how "51% of women are now living without a spouse," and copped some criticism for including 15 year olds in that total of women. Some of the criticism revolved round the mathematical confusion between ≥ and >. Around such weighty matters does our public discourse revolve! Is the inequality strict or not?

But the better—more amusing—part of the debate was witnessing the outrage that 15 year olds were counted as women. It may shock modern morals to know that back in the late nineteenth century girls could marry as young as twelve, and sometimes earlier. The common law rule was that

If a child below the legal age should marry, the marriage is not necessarily invalid, provided he or she be above the age of seven years. If the parties continue to live together after both have attained legal age, the marriage is thus ratified, but either party may disaffirm it by ceasing to live with the other before that time arrives.

(From Leila Robinson, The Law of Husband and Wife, 1890 [PDF])

Above seven years old ... Good thing the New York Times didn't include eight year olds in its definition of women, or we would never have heard the end of it! The careful reader will note how apparently easy it was for nine year olds to escape their premature marriages, they "just" had to leave their spouse. Except that provisions in the common law for child marriage were not to allow play dates to turn into wedding ceremonies, but to unite families through marriage as a largely economic transaction. So, any children so united at an early age would likely have had little volition to leave their new spouse. It was this residual provision for the elite to marry their children young that survived into the nineteenth century. But with better means for families to combine their economic interests the rationale for child marriage was lost, yet the legal grounding for it survived. Few laws are passed with an expiration date. Provisions like this can hang around on the books for years without much use, only to be rediscovered as an "outrage" to modern sensibilities that must be corrected.

But the thing is, or was ... that by the late nineteenth century few early-to-mid-teenage "women" took advantage of their freedom to marry. In 1880 a scant 0.07% of 12 year old girls were married. Even at 15 just 1.4% were married, 4.2% at 16 and then 9.3% at 17, 14.5% at 18, and 25.6% at 19. 15 year olds were not rushing to the altar in the late nineteenth century, but 19 year olds were. In other words, the upward revision in the minimum age to legally marry has not been the cause of declining early-teenage marriage. For historical comparability it's completely appropriate to include 15 year olds with other women. But I wouldn't advise any girl to get married at that age. Unless he's really rich ...

February 12, 2007

Civilization?

Discuss.

From the Appleton Post Crescent (Appleton, Wisconsin), Tuesday 21 June 1921, p.4.

January 28, 2007

Death of a downtown department store

Filene's Basement flagship store in Boston is closing, if apparently only temporarily. Though it is now no longer part of the Filene's chain, it began as a way to sell discounted items from Edward Filene's department store. In the historiography of department stores, Filene's is significant because Susan Porter Benson used the store's archives (particularly its staff magazine) for her Counter Cultures book, where modern department store historiography really begins.

While I still believe the death of the department store has been exaggerated, this is sad news.

January 12, 2007

It didn't [really] happen there, either

Seymour Martin Lipset has died (see here and here for commentary and round-up), and hopefully taken to his grave the mis-specified question of why there is no socialist party in the United States.

I say that with a great deal of admiration for Lipset's career, research interests, and writing. His writing was provocative in the best way, his research comparing Canada and the United States illuminated our understanding of both those countries (and others), and proved the basis for a long career. As one long interested in at least dabbling in comparative history you have to admire and engage Lipset's work. You do have to wonder a little how someone can make a career out of the logical trap of seeing the United States as "exceptional," yet also open to understanding by comparison.

Lipset was scarcely responsible for originating the question, since Werner Sombart got in well before him with his 1906 book, Why is there no socialism in the United States? (Google books link in German only!) Yet there was socialism in the United States. Not as a governing party anywhere, not as a winning political movement (unless you count wins against other left-wingers, which socialists have more often specialized in achieving), but certainly as an animating idea in the heads of many laborers and intellectuals. Lipset re-specified this already badly specified question a little by asking why there wasn't really even a social democratic party in the United States.

The changing question gives some of its own answer: the supposedly socialist Labo[u]r parties of Australasia and Britain had become social democratic to actually gain and maintain governments. As a swag of recent literature shows the actual policy differences between social democratic governments in Canada and Australasia, and American Democratic administrations were smaller than the difference in rhetoric would imply. Moreover, it's quite clear that the parties saw themselves as representing the same elements and ideas in their respective polities. The Australasian Labour parties saw the Democratic party as their American counterpart. While population differences meant the relationship was asymmetric, Democrats who did look abroad for inspiration saw the Labo[u]r parties.

The substantive difference to be explained is how socialist and social democratic ideas were incorporated into national governments in different ways in different places. As Lipset noted, socialists did win office in the United States. At the local and state level. But national office was something else. To win and maintain office, the Labour parties had to abandon much of what made them truly socialist.

The largest difference in policy between the Democratic party and the Labour parties would appear to be over national government ownership of companies. Specifically, in Australasia and Britain socialism became watered down to the national government owning the "commanding heights" of the economy: airlines, banks, energy and much else besides. Yet even here, the socialism was thin, and the contrasts with the United States overdrawn. For example, the federal government owns substantial amounts of land, particularly in the western states, that have been leased cheaply to private farmers. Fannie Mae was and continues to be a massive intervention in the residential property market by the federal government.

The arguments social democratic parties made for nationalizing businesses veered away from socialism, and towards market failures (often monopoly) and ensuring social opportunity for individuals and families—arguments similar to those made for United States federal government interventions in the economy. It remains broadly true also that the federal government is somewhat less important in the United States than the national governments in Australasia and Canada. A true accounting of the success of social democratic ideas would have to trace them across the states and provinces as well. United States governments (state and federal) have, broadly speaking, relied more on regulation and subsidy than outright ownership of private business. Placing some sort of value on these regulatory interventions, subsidies and tax breaks, and evaluating the rhetoric surrounding them would probably show smaller differences in the success of socialism or social democracy than Lipset allows.

Lipset's point that the Democratic party has never been a true social democratic party is mostly well made. If (if!) the Democratic party had evolved in the North only, perhaps it might have become a social democratic party. But for a century after the Civil War it remained the political vehicle for segregationist southern whites. If anything is allowed to stand for a single explanation of why social democracy did not flourish in the United States, that would be it.

December 18, 2006

Tokyo Olympiad

Anyone with any interest in running history should rent and watch Tokyo Olympiad. Directed and produced by Kon Ichikawa this is the best moving footage of the Olympics I've seen from before the era of mass-televised coverage. The movie is in color, which instantly sets it apart from all the other Tokyo coverage I've seen (e.g; these YouTube links) If you are expecting, say, full coverage of the 10,000m you'll be disappointed. But they do have 3 minutes in full, clear color including the whole last lap and it is amazing to see how many lapped runners Mills, Gammoudi and Clarke had to pass as they swapped the lead in the last 400m. Other, shorter, races are covered in full.

The coverage is artistic, rather than functional, There could be coverage of more events in its 170 minutes. You might get frustrated at the women's 80m hurdles being replayed from multiple angles—from the front, focusing on their leg muscles etc—while the men's 1500m gets only the briefest finish shot. But that would be to miss Ichikawa's intentions of recording the human drama and artistry of the Olympics.

It is not entirely track and field, with gymnastics and swimming also being covered. But the "other sports" get surprisingly little coverage. Track and field, and especially Abebe Bikila's marathon, receive the most footage.

There is no plot to the coverage, so it's quite possible to watch it in snippets when you have the chance. I've been watching it while doing my daily stretches. It might make for good relief from boredom on the treadmill. However you watch it, if you instantly recognize some of these names—Hayes, Clarke, Gammoudi, Packer, Roelants, Odlozil, Tyus—you'll get more than a little enjoyment out of this film.

Links: New York Times review. Wikipedia

November 30, 2006

Even better than the microfilm scanner

A couple of weeks ago I waxed poetic about the beauties of the microfilm/fiche scanner. Now I've discovered something quicker and often higher quality: using your digital camera to take photos of the microfilm screen.

One of the disadvantages of the microfilm scanner compared to the digital camera is speed. My best estimate is that in an hour you can take 400 digital photos or 130 scanned microfilm images. That's a substantial difference.

To do this well you will need a tripod so that you can hold the camera steady. You can get a perfectly adequate tripod for these purposes for $30, perhaps less. Or you may already own one. Then it's simple. Line up the camera so that is horizontal and facing at the microfilm screen, put your camera on the setting you use for taking photos of documents, and snap away to your heart's content.

So far I have only done this at my own university's library. There some of the staff and other patrons have just looked at me a little quizically about the tripod bag I'm carrying. It has an uncanny resemblance to a bag you might carry a gun in. No telling what the policies of other archives are about bringing in tripods, so you wouldn't want to rely on this method for reproducing material off microfilm. But a time saving tip worth knowing about if you need to reproduce microfilm images.

As always with microfilm the quality of your image will depend on the quality of the original microfilming. This varies tremendously, but the great thing about digital images of microfilm is that you can use photo editing software to alter the black-white balance to improve legibility if there are serious problems with the original microfilm copy.

October 30, 2006

Shopping your ideas

Earlier this week the New Jersey Supreme Court ruled that there was no governmental purpose in denying same-sex couples the benefits of marriage, and that the state had six months to remedy this. Gay marriage, per se, did not have to be one of the remedies, civil unions would also do.

In passing I'll note that this ruling has attracted much less public attention than previous rulings in Massachusetts and Vermont, which might suggest that American politics is heading towards some kind of compromise on this.

While there has been less debate about the decision you don't have to look hard to find [mostly Republican and right-leaning] people criticizing the courts for making this decision. It's telling that the conservative response is to criticize the venue of the decision—the courts— and not (entirely) the decision itself. It's fair to say that until very recently conservative parties in Anglo-American democracies saw the courts as the bulwark of tradition and order against populist change.

It's striking that in America there is a populist right that sees the judiciary and the common law as anti-democratic and revolutionary. Historically conservatives saw the courts as a bulwark against populist democratic change. There are traces of this attitude in Australasia, Canada and Britain, but it's less pronounced because social movements have not used the courts to try and achieve social change quite as much. Perhaps that is for the better, since changes are achieved with democratic support, but I suspect that it reflects rationally different choices in political strategy contingent on legislative and judicial structure.

Now, I'm no lawyer, but one of the defining characteristics of Anglo-American government is that laws are made both by the legislative/executive branches (statue law), and by judges interpreting the law in cases (common law). In almost every setting groups seeking social change use both mechanisms to try and affect change. This is such an established, bipartisan part of our broad political heritage that current critiques of it by people opposed to gay marriage are, I suspect, largely disengenuous.

For the sake of argument, wandering away from the issue at hand, look at the movement for the 8 hour day. Unions campaigned for this at three levels

- Trying to achieve it through contracts with individual employers

- Multi-employer contract negotiations (particularly the Australian and New Zealand arbitration systems

- Legislative restrictions on working hours.

The 8 hour day was not achieved in any country in one go; it was achieved incrementally through success in different legal venues. Same with most other social changes one cares to look at.

Venue shopping by political and social movements is an inherent part of the Anglo-American political and legal structure. If some groups really do feel those rules of the "game" are unfair and should be changed, that's a problem, but I'm inclined to guess that for now they're being disengenuous and will happily shop their own ideas round whatever sympathetic legislature or court they feel will take them.

October 20, 2006

Tip o' the day

Microfilm scanners are a wonderful invention, and I'm so enamored with them that in writing this post I browsed the web to see what they cost. At least as much as the top of the line Apple Powerbook and maybe as much as a VW Passat to put it in terms of other desirable items. Of course, the relative prices may change. Not buying any of those things for myself any time soon ...

Anyway, here's my tip for your microfilm scanning. As best I can tell what the scanner does is similar to what an automatic focus camera does—sensing the relative amounts of white and black in the viewfinder and then capturing the image. Now if you've ever taken photos on an automatic camera you'll know they are easy to fool by composing a shot that is a mix of both dark and light areas. Same goes, it seems, for the microfilm scanners.

If you have significant amounts of the black film between the pages in your images, the digital image will not be as well exposed for the part of the image you want. Previously my preference when using the microfilm scanner was to have the black space on the side of the page, rather than cropped parts of another page. This works OK for pages that are quite dark anyway (whole pages of text). It works poorly when you are trying to capture an image of a page that has a lot of white space in it—tabular data, for example—because then the automatic exposure settings can't cope very well, and will wash out the detail you are interested in.

Bottom line advice is this: For the best exposure on microfilm scanners try capturing an image without any of the black film space between pages.

September 29, 2006

Articles or books?

This article in Perspectives is welcome news that leading historians may be giving more weight to articles than books. My view has long been that historians publish too many books and not enough articles, while economists have the opposite problem.

September 3, 2006

Miracle off 34th St

Papers around the country are leading, or at least leading their business sections, with the story of how Federated is changing venerable old stores like Marshall Fields, Kaufmann's, and Foley's into Macy's.

All of the stories, though locally written and not from the wire services, have the same basic structure. They note the historic (centuries old!) roots of the store, and then use the occasion of the change-over to Macys to quote "retail consultants" saying things like

department stores have become dinosaurs ... [t]he department store model is eroding. Business models don't last forever

and (these are different people)

The whole department store base is questionable today

and

the power of such plans to inject new life into traditional department stores will prove out only over time, just as the segment took many years to decline

Color me just a little sceptical of the near-uniform pessimism about the prospects for department stores from "retail consultants." Now, it's not as if every business takeover story is revealed to be far-sighted prescience, but if the prospects for department stores were that bad, why would Federated be doubing down its investment in the sector?

A little historical perspective on this goes a long way.

Been here before

This is also a newspaper story I've seen before. If the department store is dying it is taking a mighty long time. You can read similar predictions from 1930s retail consultants when Woolworths was growing rapidly. When did you last shop at an American Woolworths? Quite a while ago. That's right.

Department store consolidation began in the 1920s, in the sense of consolidated ownership. But operations, from the name of the store to purchasing, were not really co-ordinated across these groups until computerized point-of-sale systems became both common and reliable. So, there is something different to what is going on today with greater centralization of purchasing and management by Federated.

As to whether department stores will survive, it's a basic point, but easily forgotten by some business journalists that just because you aren't growing doesn't mean you can't be consistently profitable. Now, department stores have had trouble being consistently profitable, but it's still worth remembering down the road. Department stores might not be the newest thing on the block, but they can rake in a steady cash flow which is no small advantage in any business.

What do department stores do, anyway?

Nearly all of the press coverage pits department stores against Target and Walmart, because they're all large and sell a variety of goods. Well, so does Home Depot if you think about it like that.

Let's start on the demand side. The demand for stores which sell a wide variety of apparently, and often genuinely, unrelated products is fundamentally a demand to save time. That's why the "big box" retailers have grown rapidly recently--people can and do buy 96 rolls of toilet paper at a time because the fixed time involved in buying 12 is about the same. Same goes for department stores, whose early business model was all about encouraging the idea you could get everything you wanted there. This had a lot of appeal before World War II when work hours were significantly longer than they are now.

On the other side of the market, the shopping mall has eroded some of the advantages of the department store. It is possible to visit multiple stores, and get all the goods you might have previously purchased at one department store.

One of the advantages department stores had over competitors (and some still do) is that situated downtown they were at the hub of public and private transport networks in their city. Not so much anymore (though there are exceptions in Chicago and New York, at least) in the United States. The real story here is the slow decline of downtown shopping in the United States, a decline aided and abetted by politicians and private business over a long time. Perhaps, perhaps, if gas prices stay high and American cities develop public transport that people feel comfortable using for shopping this will reverse. Downtowns have not died everywhere, and still have enough physical and locational capital invested in them, that they may revive.

To put it more simply, one shouldn't confuse the decline of the downtown department store with the decline of the department store itself.

On the other side of the market, department stores are fundamentally about aggregating a range of functions that have some scale economies when combined over a diverse selection of products. The most obvious are real estate management, labor relations, financial control, and advertising. Consolidation of stores into larger chains merely continues that search for scale economies further up the management hierarchy.

The Federated/Macy's expansion has better prospects of succeeding than previous attempts, if for no other reason than the previously cited change in technology. Historically department stores did rely on the local intelligence of department managers and salespeople to determine what to buy and sell because accounting systems were paper-based and communicating information across a large number of people, or across the country, was relatively slow and expensive.

Federated claims that one of their changes will be to target discounts and sales to customers who have an account with them, and reward them for shopping with the store. While this was possible back-in-the-day, it's cheaper to do on a large scale now, and makes sense. What department stores offer is not exclusive, you can get it elsewhere, and "loyalty" schemes are a rational attempt to bind customers to particular stores.

The key, as it probably ever was, for department stores is the merchandising side. If they can compete with the specialty clothing and housewares stores on the merchandise side, and offer the benefits of saving time, and accumulating loyalty rewards across combined purchases, department stores will probably survive. There is still a place for the salespeople, however, and I don't say that just out of misguided affection from having studied them.

While it's true that Sears and Montgomery Wards started in mail order, and that some department stores did well at mail order (the internet shopping of 1913), department stores' competitive advantage right now is going to be in selling goods people like to try on, touch, and experiment with before buying. It's just more difficult to try on pants online, right? In the end what department stores will be selling, over and above the goods, is what they always claimed to be in the business of providing: good service. If your pants don't fit quite right, you can come back and get them exchanged by an actual human being who is paid to pretend to care in a more convincing way than the person on "live chat" at the internet store.

Department stores are not the hot new business innovation of tomorrow, but they'll be around in some form for decades to come.

August 3, 2006

East of Eden

It's easy to think of the situation in the Middle East as intractable, innate and insoluble—as if the current crisis, tensions, war, whatever you wish to call it, had been pre-destined since various improbable events like floods and burning bushes. But it's not. The specific conflict we're seeing now is entirely due to the founding and existence of Israel, which has itself only existed since 1948. Less than sixty years, which is an eternity going forward, but really not so long for historians looking backward. I mean this not to take sides on the question of Zionism or a Palestinian state, but rather that if Israel wasn't there we wouldn't have the current specific conflict. In the end that's a rather trivial statement. I think it fair to speculate, though it could never be shown, that even if Israel did not exist (if the Jewish state has been somewhere in Africa or North America) the Middle East would still not be filled with stable, democratic governments. Countries with borders shaped oddly by departing colonial powers and economies dependent on resource extraction tend that way.

Even going back fifty years you can see how dramatically things can turn. That much is clear from the Guardian's recent retrospective on the Suez crisis. In the current crisis, Israel and the United States are closely allied, with Britain at a small remove, and France seen by supporters of the Israeli government as a potentially duplicitous friend of autocratic regimes. But fifty years ago it was France, Britain and Israel that invaded Egypt while a Republican President in the United States urged caution, and worked to undermine the trio's plan for a military strike on Egypt. And then there's this fascinating backdrop to the whole disasterous caper into the canal: that before they invaded Egypt, Britain had plans for how to invade Israel if that proved necessary to fulfil treaty obligations with Arab states.