Why

Blame Smallpox?

The Death of the Inca Huayna Capac and the Demographic Destruction of

Tawantinsuyu (Ancient

Robert

McCaa, Aleta Nimlos, and Teodoro Hampe Martínez

For a pdf version of this paper click here

Será

hombre como de cuarenta años, de mediana estatura, moderno

y con unas pecas de viruelas en la cara…

—description of Inca Titu Cusi Yupanqui, 18 June1565[1]

Introduction

Smallpox is

widely blamed for the death of the Inca Huayna Capac and blamed as well for the

enormous demographic catastrophe which enveloped Ancient Peru (Tawantinsuyu). The historical canon now teaches that

smallpox ravaged this virgin soil population before 1530, that is, before

Francisco Pizarro and his band of adventurers established a base on the South

American continent.[2] Nevertheless the documentary evidence for the

existence of a smallpox epidemic in this region before 1558 is both thin and

contradictory. In contrast to

We advocate a

more skeptical approach to assessing the causes of both the Inca’s death and

the demographic destruction of Tawantinsuyu.

While the continued scrutiny of early colonial chronicles may yet

provide conclusive evidence, we urge historians to take greater account of a

wider-range of unconventional sources, such as linguistic evidence from early

Quechua dictionaries, lessons learned from the World Health Organization’s

global campaign to eradicate smallpox, physical descriptions of native peoples,

and the examination of mummies for signs of smallpox, or the lack thereof. As in the epigraph, early descriptions of

native peoples, which remark on the presence of pockmarks, may settle the

question regarding the first appearance of the dreaded disease in the

From our

re-examination of early chronicles (see table 1), linguistic evidence in three

early dictionaries (table 3), physical descriptions of pock marked native

peoples (or the lack thereof before 1558), we conclude that, as in the

Caribbean also in the Andean region, the preponderance of the evidence points

to a late introduction of smallpox—a quarter center after initial contact (in 1518

and 1558, respectively), after an enormous demographic devastation had already

occurred.[3] In

The Death of Huayna Capac

The Inca Huayna

Capac’s sudden death, at the peak of his wealth and power, is unique because no

other Inca ruler was reported to have died so mysteriously. The demise of

Huayna Capac is quite remarkable. Of all

the great Incas only his is told with such an abundance of details, although

the evidence is rather scanty and conflicting when compared with the death of

the Aztec ruler Cuitlahuatzin, whose death from smallpox is unquestionable.[5] As was customary for Inca rulers, Huayna

Capac’s body was embalmed on the spot with the heart and other internal organs

removed. The mummy was dressed in

precious mantles and adorned with feathers and gold, before being conducted on

a litter to

Francisco Pizarro and his troop first received

word of Huayna Capac’s death around October 1531 while encamped on the

The most

important early chroniclers writing on the decades of conquest agree that

Huayna Capac died suddenly of a mysterious illness, but there is remarkable

uncertainty regarding the cause or symptoms.

According to our count, smallpox is the explanation given by six of the

seventeen chroniclers who state one or more causes (see Table 1). Fever is favored by three, measles by two, severe

rash or inflammation of the skin by two, and one each writes of boils, “perlesía”,

“romadizo”, pain, or melancholy.

Clearly Huayna Capac’s death was considered important to most

chroniclers, but the exact cause or symptoms were puzzling. Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa, Martín

de Murúa and the Inca Garcilaso de la Vega constrain their descriptions of the

cause with phrases such as “cuentan que”,

“unos dicen … otros dicen”, and “aunque otros dicen”. Were chroniclers who used this sort of phrasing seeking

to caution the reader that the author was unable to judge and instead was

relying on hearsay?

Table 1 near here (20 early

chronicles)

Interpreting the chronicles

The

linguistic challenge faced by the chroniclers, all of whom were “cristianos” writing in Spanish was considerable, even though

native quipucamayocs, amautas, and relatives of the Incas were

claimed as informants. Illness and pestilence was well known in Ancient

Peru. Guaman Poma, for example, explains

that September was the month for getting rid of “pestilencias y enfermedades”,

“when all the houses and streets were flooded with water and cleaned throughout

the kingdom” (p. 255). The author’s

mother tongue was Quechua and his 1200 page manuscript incorporates an

extensive Quechua vocabulary, including several terms regarding illness (cf. p.

255, “oncuy”, “uncuy”, “oncoy”, etc.)/

The earliest testimony regarding the death of Huayna Capac is that of

the Inca Atahualpa himself, as related by Francisco de Xerez, who described

Huayna Capac as dying of “aquella enfermedad” (see Table 1). It is a pity that Xerez allowed this

ill-defined demonstrative pronoun to enter the record.

One of the most-trustworthy early chroniclers, Juan de Betanzos, was

married to a niece and adopted daughter of the Inca Huayna Capac.[9] Betanzos’ opus, which attributes the Inca’s

death to “una sarna y lepra”, was completed in 1552 but not published in its

entirety, including the chapter on Huayna Capac’s death, until 1987. Historians only recently gained the

opportunity to take into account the complete narrative. Given the early date of the chronicle, its

reliance on the Inca’s immediate family as informants, and the author’s

extraordinary zeal for knowledge of the Inca past, one might expect that his

testimony that the Inca died of “una sarna y lepra” might have called for a

re-assessment of the smallpox thesis.

Unfortunately this has not been the case. Cook argues that “sarna” could be mistaken

for smallpox, and that Betanzos’ text “parallels” that of the widely cited

Cieza de Leon (Cook 1998:76-7). To permit readers to examine the narrative

directly, we quote Betanzos’ text in extenso in Appendix B. The key phrase is reads (p. 200):

“...le dio una enfermedad la cual enfermedad le quitó el

juicio y entendimiento y dióle una sarna y lepra que le puso muy debilitado...”

Note that the chronicler uses here the indefinite article “una” with respect to

“sarna”. This connotes a nonspecific nature or vagueness of identity, as

opposed to the use of the very specific “la” in connection with the words sarna

and lepra. Is the author using

lepra as an adjective to describe the cutaneous eruptions of smallpox, measles,

typhus, verruga, or other disease involving eruptions of the skin? Or is he attempting to describe something

like sarna and lepra, a severe inflammation of the skin, but not smallpox,

measles or any other disease common to the vocabulary of a mid-16th

century Spanish writer? Covarrubias defines lepra as

“un género de sarna que cubre el cuerpo” and sarna as “una especie de

lepra”. He also writes that there are

many types of lepra that covers the skin with ugly scabs or scale.

It is significant that Lastres, in 1951 and

then again in 1954, stated that he was “inclined” to think smallpox was the

cause of Huayna Capac’s death.[10]

However, as we know, he was unable to consult Betanzos’s chronicle for it was

first published three decades later.

Chronicles by Pablos or Ortiguera came later as well. In the 1950s, Lastres’ research and writing

on the subject peaked. He discussed the

smallpox thesis in three different books.

Rarely cited, his last, our

favorite, was published in 1957. Here (La

Salud Pública y la Prevención de la Viruela en el Perú.

“Aunque hay algunos datos que

hacen presumir que la epidemia que diezmó los ejércitos del Emperador indio

Huayna Cápac fuera de viruela como lo hemos consignado en un trabajo anterior

(1) sin embargo, dadas las interrogantes que se ciernen sobre este episodio

epidemiológico, prefiere pasarlo por alto, y comenzar el estudio [de viruelas]

desde la época de la llegada de los españoles en 1532.

As table 2 shows, only Guerra, writing four

decades later, examined more accounts than Lastres, but even so the most

prolific writer on the subject did not consider three chronicles, two of which

propose alternative explanations:

Borregán (perlesía), Pablos (lepra incurable), or Ortiguera (viruelas).

Pedro Cieza

de León is the favorite source for modern historians who embrace the smallpox

hypothesis, but here too there is a new edition, from a manuscript in the

Vatican Library, discovered and transcribed in 1985 by editor Francesca

Cantú. The key phrase reads:

Pues, estando Guaynacapa en el

Quito con grandes conpañas de jentes que tenía y los demás señores de su

tierra… quentan que vino una gran pestilençia de viruelas tan contajiosa que

murieron más de dozientas mill ánimas en todas las comarcas, porque fue

general; y dándole a él el mal no fue parte todo lo dicho para librarlo de la

muerte, porquel gran Dios no era dello servido.[11]

No historian has made much of the fact that Cieza de León prefaces his

statement as to cause of death with the phrase “quentan que”. Indeed Cieza de León is not alone in hedging

his remarks, as noted above. A

comprehensive evaluation of the narratives on the cause of death of Huayna

Capac should take into account such cautionary expressions.

Some decades later, in his 1582 history of the

city of Cuenca and the province of Quito, Padre Hernando Pablos ―

condensing the popular versions in the very region where the final illness of

Huayna Capac broke out ― affirmed that there occurred a “pestilencia muy

grande en que murieron innumerable gente de un sarampión, que se abrían todos

de una lepra incurable, de la cual murió este señor Guaina Capac, al cual

salaron y llevaron al Cuzco a enterrar…” (Pablos, 1995: 271). What stands out

in the excerpt is the use of the indefinite article to describe lepra.

Note also that measles cannot be confused with “leprosy”, which clearly

at this time included a variety of ailments other than the flesh-eating

disease.

In the 1630 Memorial de las historias

Deconstructing

the auguries and portents as Christian myth represented in this and other

chronicles is beyond the scope of this paper, yet the frequency with which

native portents are cited by chroniclers is striking. As early as 1544, a text by Vaca de Castro

already has the Inca Huayna Capac foreseeing harsh times:

“Guaina Capac Inga en esta pacificacion y gobierno de Quito, entraron en la tierra los

primeros cristianos, primeros descubridores, con el marques don Francisco

Pizarro, que fueron los trece de la isla

del Gallo... Guaina Capac Inga, sabido de cómo habían entrado los

cristianos en la tierra y le dieron noticia déllos, luego dijo que había de

haber grande [sic] trabajo en la tierra y grandes novedades; y al tiempo que se

estaba muriendo de la pestilencia de las viruelas que fué el año siguiente...”[13]

Vaca de Castro

was also the first chronicler to state that smallpox was the cause of Huayna

Capac’s death. Later, Pedro Pizarro

recounted Huayna Capac’s vision of dwarfs, preceding the smallpox attack:

Pues estando en esta obra dio entre

ellos una enfermedad de viruelas, nunca entre ellos vista, la cual mató muchos

indios; y estando Guainacapa encerrado en sus ayunos que acostumbraban hacer,

que era estar solos en un aposento y no llegar a mujer, no comer sal ni ají en

lo que les guisaban, ni beber chicha (estaban de esta manera nueve días; otras

veces, tres), pues estando Guainacápac en este ayuno, dicen que le entraron

tres indios nunca vistos, muy pequeños como enanos, adonde él estaba, y le

dijeron: ‘Inga, venímoste a llamar’, y como él vido esta visión y esto que le

dijeron, dio voces a los suyos, y entrando que entraron, desaparecieron estos

tres ya dichos, que no les vió nadie salvo el Guaina Capa, y a los suyos dijo:

“¿Qué es de esos enanos que me vinieron a llamar?” Respondiéronle: “No los hemos visto.” Entonces dijo el Guaina Capa: “Morir tengo”,

y luego enfermó del mal de las viruelas.

Pues estando así muy enfermo, despacharon mensajeros a Pachacama… ¿qué

harían para la salud de Guainacapa?, y los hechiceros que hablaban con el

demonio, lo preguntaron a su ídolo, y el demonio habló en el ídolo y les dijo

que lo sacasen al sol y luego sanaría.

Pues haciéndolo ansí fué a la contra, que en poniéndole al sol murió

este Guainacapa… y había diez años que era muerto cuando entramos en esta

tierra…”[14]

Royal officials

such as Vaca de Castro and relatives of the initial band of conquistadores,

such as Pedro Pizarro, had ample reason to blame smallpox for the death of

Huayna Capac and the destruction of the native populations. Every Indian who died of smallpox was one

less death to be blamed on the conquistadores or government officials. Even native chroniclers, such as Juan de

Santa Cruz Pachacuti Salcamayhua, relied upon the trope of sorcerers and seers

to explain the Inca’s defeat:

…en donde estando caminando el ynga

da Rayos a los pies y de alli buelbe pª quito teniendo por mal aguero y qdo yba

hazia la mar con su campo se vido a media anoche vesiblemte çercado de millon

de millon de hombres y no sab<ia>en [ni supieron] quien fueron a esto <dizen

que> dixo que eran almas de los bibos q dios abia mostrado significando q

<a> abian de morir en la pestelençia tantos los quales almas dizen que

venian contra el ynga de que el ynga entiende q era su enemigo y assi toca

armas de aRebato y de alli buelbe a quito con su campo y haze fiesta de capac

raimi solemnisandole y assi a oras de comer llega vn mensajero de manta negro

el qual bessa al ynga con gran Reuerençia y le da vn putti o cajuela tapado y

con llabe y el ynga mda [al mismo ynº] que abra el qual dize que perdone

deziendo q el hazedor le mandaua el abrir a solo el ynga y visto por el ynga La

razon le abre la cajilla y de alli sale como maripossas o papelillos bolando o

esparçiendo hasta desaparesçer el qual abia sido pestelençia de sarampion y

assi dentro de dos dias muere el general mihic naca mayta con otros muchos

capitanes todos Las caras llenos de caracha y visto por el ynga mda hazer vna

cassa de piedra pª esconderse y despues se esconde en ella tapandose con la

misma piedra y alli muere y al cabo de ocho dias saca caçi medio podrido y los

embalssama y trae al cuzco En andas como si fuera bibo y bien bestido y armado

y en la mano con su ttopa yauri o suntor paucar y mete en el cuzco con gran

fiesta… Por la gente al Cuerpo muerto de guayna capac hazia Reueª y despues de

aber metido en la sepultura de sus passados pregona el llanto general por su

muerte q hasta entonçes no abia nueba de su muerte…”[15]

Chroniclers may also have blamed smallpox for the death of Huayna Capac

and the destruction of the native peoples, as a readily believable and wholly

excusable cause, one that would resonate with Christian readers. With

apparent frustration, Lastres observed in 1954 (p. 26):

Hay que convenir en que es

materialmente imposible hacer diagnósticos retrospectivos muy precisos, porque

los cronistas son gente empírica y dan descripciones muy arbitrarias. Además, que todos ellos escriben de oídas y

muchos repiten lo que dijeron los primeros narradores.

Would Lastres have been less “inclined” to

embrace the smallpox hypothesis if he had examined more of the evidence? Did his “inclination” take into account the

ominous “cuentan que” or “se dicen” preceding several ascriptions?

A symptomatic picture of the disease that caused the death of the Inca

Huayna Capac emerges. He

became ill in the region of Tomebamba, suffered from chills and fever and

became delirious. His skin broke out

with itchy eruptions that became swollen and pustular. They eventually produced scabs. His illness

progressed swiftly, and as it did, at some point, the Inca became unable to

move. Lastres

(1954: 21) points out that “éste tuvo un proceso febril precedido de

escalofríos y que lluego sobrevinieron síntomas de excitación psíquica,

delirio, coma y muerte...” What we cannot do with any certainty is to

ascribe a cause of death. Moreover, if

we are not to be entrapped by a creationist myth, we must consider the

possibility of a disease that may have gone extinct.

Discrepancies

among the sources should caution historians from facile spinning of

inconsistencies in the historical record or, indeed, of cherry-picking only

those sources that agree with the smallpox hypothesis (see Table 2). While no modern historian asserts flatly that

Huayna Capac died of smallpox—on the contrary, most state that their conclusion

is only an “inclination” (Lastres 1954) or “best guess” (Crosby 1972:52)—those

who emphasize the primacy of virgin soil epidemics proceed to write their story

as though the issue was incontrovertible.[16] Grand narratives, such as William McNeill’s Plagues

and Peoples and Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs and Steel, sweep over

the ambiguities.[17]

A

linguistic reassessment

Before 1558,

when both Spanish and Quechua speakers experienced an outbreak of smallpox in

common, translating from the Quechua to Spanish was particularly

uncertain. The smallpox epidemic of

1558-9 was a significant linguistic event because from that time Spanish and

Quechua speakers could discuss the disease based on mutual experience. In 1954,

the distinguished Peruvian medical historian, Juan B. Lastres, observed that

the first Quechua dictionary, published in 1560, the Lexicon of P.

Domingo de Santo Tomas, had no word for smallpox—and therefore, Lastres

concluded, smallpox had not existed in ancient Peru. Lastres observed that finally in 1608 Fray

Diego Gonzalez Holguín’s dictionary distinguished smallpox (huchuy muru uncoy)

from measles (hutun muru uncoy). Lastres

explained that in both dictionaries “muru” carried the meaning of round

spot (such as “muru cauallo” for spotted horse). Lastres concluded his linguistic

analysis, as follows:

En realidad

la voz ‘muru’, en los

diccionarios quechuas, se traduce como ‘mancha redondeada’; y el proceso

llamado en quechua “muru onccoy” sería, pues, ‘enfermedad de mancha’,

una erupción cutánea caracterizada por manchas redondas que radican en la piel

puede representar variados procesos, como viruela, sarampión, tifus

exantemático, la misma verruga, o aún procesos eczematosos.[18]

What Lastres

did not note was that by 1586 with the publication of Vocabulario y phrasis

(attributed to Antonio Ricardo) the phrase “muru uncoy” had already come

into use, to refer to smallpox.[19]

Table 3 near here (disease

terms in early Quechua dictionaries)

Lastres’s

linguistic findings and the fact that he did not consider the Vocabulario y

phrasis stimulate a broader survey of terms in all three of the earliest

Quechua dictionaries (Table 2): 1560

(Santo Tomas), 1586 (“Ricardo”[20]),

and 1608 (Gonzalez Holguín). Ours is the

first analysis of all three dictionaries with respect to smallpox. To provide comparative context we discuss as

well terms for other diseases, illnesses, and even destruction.

Domingo de

Santo Tomas has the distinction not only of composing the first Quechua-Spanish

dictionary, following two decades of pioneering linguistic fieldwork, but also

of capturing the Quechua language before significant linguistic mixing had

occurred. According

to Raul Porras Barrenechea, the editor of the modern edition of the Lexicon,

“En él hay todavía muy pocos aportes de origen español u occidental. No ha habido tiempo para el trasplante cultural sino de muy

pocas palabras” (1951:xviii). “Cavalloc”

(caballo) is identified as one of those words, as is “quillay” (hierro, from

the ancient word meaning literally “metal”).

It is significant that

A systematic

search of the Spanish yields Quechua words or phrases in all three dictionaries

for berruga, calenturas, cundir, curar, dolencia, enfermedad mortal, hambre,

lepra, muerto de hambre, peca de la cara, romadizo and sarna. It is striking, as noted by Lastres, that in

the earliest dictionary, which was based on almost two decades of study but

completed before the smallpox epidemic of 1558, no term existed for smallpox or

measles. These first appear in the Vocabulario

of 1586 and continue in Gonzalez Holguín’s work (1608), along with contagión,

infección, pestilencia, remedio, and “pegar” (as in fish-paste), describing the

means of transmitting smallpox and other contagious diseases.[21] In this last dictionary of the three, only

two new terms appear in this regard:

enfermedad de la mancha and mal

de viruelas o sarampion. Both carry

identical translations: muru oncoy.

If smallpox

caused such devastation in

To round out

this linguistic excursion, we must also consider terms that do not appear in

any of the dictionaries. From a list of

other illnesses, prepared before examining the dictionaries, the following

terms do not occur: dolores de costado, eczema, exantemático, erupción,

paludismo, peste, picado, plaga, tabardete, tifus, and tos. We have left for linguists the task of

searching out terms referring to disease in Quechua that might have more

metaphorical translations into the Spanish.

A thorough

analysis would compare the appearance of various types of terms with those for

disease (and would require the assistance of an expert Quechua linguist). Perhaps it is a matter that later dictionaries

were simply more complete. For purposes

of comparing the linguistic record on disease with that on destruction, Table 4

analyzes 16 terms on destruction and decay in the three earliest

Quechua-Spanish dictionaries. The list

is composed of words drawn from sixteenth-century narrative Spanish sources

cited by the historian Carlos Sempat Assadourian who argues that destruction,

not disease, was the principal cause of the demographic disaster.[22] The earliest dictionary does not translate

seven of these terms into the Quecha (alboroto*, despoblar pueblo*, destrozar

en guerra, empalar, matanza, melancolía, or osario*). Of these the three starred words are recorded

in the second dictionary. All appear in

the third. On the other hand, none of

these terms are as singularly destructive as smallpox is supposed to have been.

While arguments could be advanced to explain the absence from the first

dictionary of any of the half dozen terms commonly associated with smallpox, we

conclude that the absence of evidence is more likely due to the absence of the

phenomenon itself.

Table 4 near here (Destruction

terms in early quechua dictionaries)

Evidence of the absence of

smallpox from the lack of descriptions of pockmarks

Knowledge of

smallpox has increased greatly in recent decades, yet few historians seem

acquainted with new findings in the epidemiology of the disease.[23] The

most significant for the present case is, first, the use of pockmarks, in

modern times, to certify the extinction of natural smallpox, and, for historical

times, to date the occurrence of epidemics.

Second, but equally important, is new evidence regarding the rather low

communicability of the disease.

While

historians focus their attention on the death of Huayna Capac, silences in the

record of smallpox among the Andean population have gone ignored. In contrast, in the case of

In contrast,

in

It was reasoned that, if these surveys included all

children up to 15 years of age, there would be some who had had smallpox when

it was still endemic and would have pockmarks which the teams should

detect. This served as an internal

control in the survey, in that failure to detect any individuals with pockmarks

would call into question the work of the team concerned. When children with pockmarks were detected,

efforts were made to find out in which year they had contracted the disease

that had caused the scarring. Such

information was surprisingly easily obtained from most villagers. The age of the youngest pockmarked child also

provided objective evidence as to when smallpox had last occurred.

...

Failure to find pockmarks in any children born since

the occurrence of the last known case in the country provided important

evidence that transmission of variola major had been interrupted.[29]

The World Health Organization concluded (I:508) that

“it was possible through facial pockmark surveys to determine the recent past

history of smallpox.” Historians, too, have used evidence of scarring

to date epidemics. Elizabeth Fenn cites

numerous instances of references to pockmarked native peoples in the Pacific

Northwest and

If the World Health Organization accepted the absence

of pockmarks after a certain date as evidence for the eradication of smallpox

then, should not historians consider absence before a certain year as evidence

for the absence of the disease? Why do

no chroniclers of early

The relatively low

communicability of smallpox

It is easy to

understand why smallpox appeared rather late in

The sole

means of spreading smallpox was by direct contact with infected humans. While scabs contained large amounts of viral

matter and could be transported over long distances, this material was highly

fragile and was easily destroyed in the tropics by exposure to sunlight, high

temperatures or humidity.[35] During the incubation period (1-7 days), an

infected individual rarely displayed symptoms and the likelihood of

transmission was nil. Onset of the

disease was heralded by a sudden rise in body temperature to 38.5-40.5°C,

usually in 10-14 days. At that point the

individual became highly contagious for about 10 days. During the first days of fever and rash

higher frequencies of infection were observed following face-to-face contact.

Longer-range airborne infection “appears to have been very rare”, usually

assisted by mechanical ventilation, heating, or air conditioning systems. With the disease firmly established, in a day

or two a rash formed as virus particles infected epidermal cells and skin

lesions formed in a centrifugal pattern on the extremities of the body (face,

hands, and feet). In fatal cases of

normal variola major, death came between the tenth and sixteenth day. With haemorrhagic smallpox, an exceedingly

rare type about which comparatively much has been written, death typically was

precipitated from day six through twelve.

Corpses were heavily contaminated and posed a serious occupational hazard

for mortuary attendants. A second bout

of somewhat reduced fever struck survivors at the beginning of the third week,

and scabs began to separate about the same time. [36]

Smallpox was

much less contagious than influenza or malaria.

Close personal contact was required.

According to the WHO report, family members and close associates were at

greatest risk of contacting the disease (I:191):

the

overwhelming majority of secondary infections occurred in close family contacts

of overt cases of smallpox, especially in those who slept in the same room or

the same bed. Next in frequency were

those who lived in the same house; residents of other houses; residents of

other houses, even in the same compound (who would often have visited the house

of the patient), were much less likely to become infected.

Historians

typically exaggerate the speed of transmission as well. In the case of

Mesoamerican

sunflowers, tobacco, or the domestic turkey never reached

Huayna

Capac’s Mummy

As Huayna Capac’s

body was without corruption at the time immediately following his death,

certainly the telltale marks of smallpox would have been evident to the

observer, had they been present. Guaman

Poma’s artfully depicts the mummy as it is born on a litter from

Three other writers

refer to the mummy of Huayna Capac. The

Dominican friar Reginaldo de Lizárraga is silent regarding the outward

appearance of the mummified royal remains (see his discussion of the idolatry

practiced toward the Inca royal mummies as mentioned in his early seventeenth

century work, the Descripción y población

de las Indias, cf. Lizárraga, 1987: 175). If smallpox caused the death of

Huayna Capac, the pockmarks would show on his mummified tissues, as was the

case with Ramses V’s mummy in

In his Royal Commentaries

of the Incas, Garcilaso de la Vega describes seeing the mummy of Huayna

Capac, early in 1560, along with two other male mummies – certainly those of

Pachacutec (not Viracocha)[39]

and Tupac Inca Yupanqui – and two female mummies in the house of Polo de

Ondegardo. He also reports that as they were carried through the streets of

[...]

fui a la posada del licenciado Polo Ondegardo, natural de Salamanca, que era

corregidor de aquella ciudad, a besarle las manos y despedirme de él para mi

viaje. El cual, entre otros favores que me hizo, me dijo: “Pues que vais a España,

entrad en ese aposento; veréis algunos de los vuestros que he sacado a luz,

para que llevéis que contar por allá”.

En el aposento hallé cinco cuerpos de los reyes Incas, tres de varón y

dos de mujer. El uno de ellos decían los

indios que era este Inca Viracocha, mostraba bien su larga edad; tenía la

cabeza blanca como la nieve. El segundo

decían que era el gran Tupac Inca Yupanqui, que fué bisnieto de Viracocha

Inca. El tercero era Huayna Capac, hijo

de Tupac Inca Yupanqui y tatarnieto del Inca Viracocha. Los dos últimos no mostraban haber vivido

tanto; que aunque tenían canas, eran menos que las del Viracocha. [...] Los

cuerpos estaban tan enteros que no les faltaba cabello, ceja ni pestaña. Estaban con sus vestiduras como andaban en

vida. Los “llautos” en las cabezas, sin más ornamento ni insignia de las

reales. Estaban asentados, como suelen sentarse los indios y las indias; las

manos tenían cruzadas sobre el pecho; la derecha sobre la izquierda, los ojos

bajos, como que miraban al suelo (Garcilaso de la Vega, 1976, bk. 5, ch. 29).

Moreover, Garcilaso had the opportunity to

touch the hands of Huayna Capac’s mummy, “whose

fingers were like sticks”, but if he noticed the fingers as “picados de viruelas” he did not mention

it.[40] The far-reaching consequences that this

physical contact with this grand-uncle might have had on the young emigrant,

motivating him to compose afterwards in Spain a utopian view of Tawantinsuyu,

have been ably explored by psychoanalyst Max Hernández (1993: 92-93).

Huayna Capac’s mummy was by custom initially kept in his palace, the

Kasana, on the main

Some time later the mummy was transferred to his estates in

the Yucay valley so that the Spaniards would not find it. There it was kept

with much gold, silver and other riches and his “huauque”, a golden statue of

the king. It is known that early colonizers were actively searching for and

seizing many mummies both in the city of

Huayna Capac’s

mummy remained concealed by his panaqa until late 1559 when, according to

Sarmiento de Gamboa (1943, ch. 62: 151), it was found by the corregidor Polo de

Ondegardo in a house in

Documentary

evidence indicates that the rural

THE

SAN ANDRÉS HOSPITAL, LAST RESTING PLACE OF THE INCAS

Akin to the

customs of many traditional peoples, the men and women of the Inca civilization

worshiped the mummies of their ancestors, particularly of their rulers, in

whose honor ceremonies and sacrifices were organized. Towards 1560, and in

order to eradicate this so-called “idolatry”, the Viceroy Marquis of Cañete

ordered the mummified remains of three or four Incas and two Coyas – their

official wives – to be moved to the Hospital Real de San Andrés in Lima (see

the generic descriptions in Guillén Guillén, 1983; Hinojosa Cuba, 1999; Deza

and Barrera, 2001). These remains had been found in various places near

The San Andrés Hospital, the oldest in the viceroyalty of Peru and one

of the few remaining from the sixteenth century in the western hemisphere, was

founded in 1550 in order to provide health care to low-income, male inhabitants

of Spanish descent. The hospital’s original facilities included a church and

catacombs where hundreds of deceased patients were buried until early in the

nineteenth century. As an approximation to the number of skeletons still buried

in the complex, it is mentioned that in an 1876 reconstruction “it was seen,

between two thick walls, around 1,000 to 1,500 human remains” (Polo, 1877:

378).

Being an important part of the monumental circuit of downtown

The building was

eventually declared a historic landmark by the Instituto Nacional de Cultura,

on 28 December 1972 (Resolución Suprema no. 2900-72-ED). After an earthquake

caused severe structural damages to the building in October 1974, the religious

community of the Hijas de María Inmaculada abandoned this location and the

building was partially restored to accommodate a public school for girls, the

Colegio Nacional de Mujeres “Oscar Miró Quesada de la Guerra”.[43]

According to a

series of chronicles written in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the

worshipped remains of some former Inca sovereigns were placed in a patio at the

Hospital Real de San Andrés, the main hospital for the “república de españoles”

in

In the twentieth

century a formal attempt, promoted by the Sociedad de Beneficencia Pública de

Lima and conducted by the historian José de la Riva-Agüero, was made to rescue

the Inca royal mummies kept there, in the Barrios Altos neighbourhood of Lima.

Riva-Agüero and his collaborators suspended their investigation in August 1937,

under the conviction that their efforts would not be useful without the aid of

Spanish original manuscripts, i.e. depictions of the San Andrés Hospital, that

were kept in the Archivo General de Indias in Seville (see Riva-Agüero, 1966:

398-400, and Hampe Martínez, 2000b).

GEOPHYSICAL SURVEY AT THE SAN ANDRÉS HOSPITAL

In August 2001,

acting with the official permission of the Instituto Nacional de Cultura (Resolución Directoral Nacional N° 783-2001/INC), a group of archaeologists

performed a geophysical survey in the 5,500 square-meter area of the former

Hospital Real de San Andrés. This group of researchers was led by Professor

Brian S. Bauer of the Department of Anthropology, University of Chicago (a

well-known scholar and investigator of the Inca civilization in

Ground

penetrating radar (GPR), sometimes called ground probing radar, georadar,

subsurface radar or earth sounding radar, is a noninvasive electromagnetic

geophysical technique for subsurface exploration, characterization and

monitoring. It is widely used in locating lost utilities, environmental site

characterization and monitoring, agriculture, archaeological and forensic

investigation, groundwater, pavement and infrastructure characterization,

mining, ice sounding, and a host of other applications. It may be deployed from

the surface by hand or vehicle, in boreholes, between boreholes, from aircraft

and from satellites. It has the highest resolution of any geophysical method

for imaging the subsurface, with centimeter scale resolution sometimes

possible.[44]

GPR uses electromagnetic wave propagation and scattering to image,

locate and quantify changes in electrical and magnetic properties in the

ground. Depths of investigation (and resolution) are controlled by electrical

properties through conduction losses, dielectric relaxation in water,

electrochemical reactions at the mineralogical clay-water interface, scattering

losses, and (rarely) magnetic relaxation losses in iron bearing minerals. Depth

of investigation varies from less than a meter to over 5,400 meters, depending

upon material properties. Detectability of a subsurface feature depends upon

contrast in electrical and magnetic properties, and the geometric relationship

with the antenna. Quantitative interpretation through modeling can derive from

ground penetrating radar data with such information as depth, orientation, size

and shape of buried objects, density and water content of soils, and much more.

As a result of the survey, distributed in 52 grids, a map of the site

has been composed (see Appendix A) in which initially identified anomalies are

marked as dots. “Anomaly of note” refers to an anomaly at least a couple of

meters across and at more than a meter in estimated depth (assuming that a

travel time of 20 nanoseconds corresponds to about one meter in physical

depth). Screen captures of the filtered and processed data have been provided,

on eight illustrations, for the anomalies of particular interest. The Appendix

includes a table with numerical ratings for each grid on a scale of 1-5, with a

grade 1 anomaly having the most potential for further investigation.[45]

ANTHROPOLOGICAL AND PALEOPATHOLOGICAL

PROSPECTIVES

Previous bio-anthropological studies done on colonial

contexts in

While many studies have focused on the Andean anthropological record, a

remarkably scant number of them have done the same on early colonial

collections. The main reason for this is basically the lack of scientifically

excavated cemeteries or catacombs dating from the times of Spanish domination

(see Lombardi Almonacín, 1992: 2-4). On the other hand, chronicles and other

documentary sources support an increased morbidity and mortality among Native

Americans after 1492.

Despite

the uncertainty of retrieving the Inca royal mummies, previous successful

experiences studying pre-Columbian mummies permit the researchers at the

Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia in

Conclusion.

Although the current historiographical orthodoxy

attributes the death of the Inca Huayna Capac to smallpox, a more skeptical

examination of the evidence suggests that this hypothesis is unlikely. First, disagreement among the chroniclers is

more profound than many historians are wont to recognize. Second, two of the most important early

sources to report smallpox do not fully embrace the idea, and instead simply

recount a story (“cuentan que”). Third,

historians assume that smallpox was a highly contagious disease, but this too

is not the case. It is exceedingly

unlikely that smallpox could have traversed

Additional evidence, either the description of

pockmarked native peoples or mummies, including perhaps that of the Inca Huayna

Capac, signalling the presence of smallpox (or not), will be necessary to

resolve this conundrum. In the meantime,

to continue to blame smallpox for the death of Huayna Capac (and the

destruction of the native peoples of the Andean Region) without considering

alternative explanations in at least as great detail, seems to these authors an

unfortunate distortion of the historical record.

Then too there is an alternative explanation

for the destruction of Tawantinsuyu. One

of the most comprehensive and thoroughly researched is that by Carlos Sempat

Assadourian (1994). His thickly

documented analysis based on an impressively wide range of sources blames the

demographic disaster on three decades of near total war, excessive labor

demands, wholesale environmental destruction, widespread famine, and sheer

cruelty. Alien diseases are secondary

factors, dating from 1558 with the first smallpox epidemic, once the population

has already been halved.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES (to be

deleted and inserted as notes where cited)

PRIMARY SOURCES

ACOSTA, José de

(S.I.)

1977 Historia

natural y moral de las Indias [1590]. Edición facsimilar. Introducción,

apéndice y antología por Barbara G. Beddall. Valencia: Artes Gráficas Soler.

BETANZOS, Juan de

1987 Suma y narración de los incas [1551]. Edited by María del Carmen Martín Rubio. Madrid: Ediciones Atlas.

CALANCHA, Antonio de

la (O.S.A.)

1639 Corónica

moralizada del Orden de San Augustín en el Perú, con sucesos ejemplares en esta

monarquía, tomo I. Barcelona: Pedro Lacavallería.

COBO, Bernabé (S.I.)

1964a Fundación

de Lima [1639]. In Obras,

estudio preliminar y edición del P. Francisco Mateos, Madrid: Ediciones Atlas,

tomo II (Biblioteca de Autores Españoles, 92), p. 277-460.

1964b Historia

del Nuevo Mundo [1653]. In Obras,

estudio preliminar y edición del P. Francisco Mateos, Madrid: Ediciones Atlas,

tomos I y II (Biblioteca de Autores Españoles, 91-92).

GARCILASO de la

VEGA, Inca

1976 Comentarios

reales de los Incas [1609]. Prólogo, edición y cronología por Aurelio

Miró Quesada. Caracas: Biblioteca Ayacucho. 2 vols.

1977 Historia

general del Perú; segunda parte de los Comentarios reales [1617]. Lima:

Editorial Universo. 3 vols. (Colección Autores Peruanos, 13-15).

GUAMÁN POMA DE

AYALA, Felipe

1936 Nueva

corónica y buen gobierno [1615]. Edición facsimilar. Paris: Institut d’Ethnologie.

LIZÁRRAGA, Reginaldo de

1987 Descripción

del Perú, Tucumán, Río de la Plata y Chile. Edición de Ignacio

Ballesteros [1605]. Madrid: Historia 16 (Crónicas de América, 37).

ONDEGARDO, Polo

de

1916 Informaciones

acerca de la religión y gobierno de los Incas [1571]. Notas biográficas

y concordancias de los textos por Horacio H. Urteaga. Lima: Imp. y Lib.

Sanmarti (Colección de libros y documentos referentes a la historia del Perú,

3).

PABLOS, Hernando

1995 “Relación que enbio a mandar su Magestad

se hiziese desta ciudad de Cuenca y de toda su provincia” [1582]. In Relación de antigüedades de este reino

del Perú, ed. Carlos Araníbar. Lima: Fondo de

Cultura Económica.

SALINAS y CÓRDOVA, Buenaventura (O.F.M.)

1957 Memorial de las historias del Nuevo Mundo Piru [1630]. Edited by Luis E. Valcárcel.

Lima: Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos.

SANCHO de la HOZ, Pedro

1962 “Relación para Su Majestad” [1534]. In

Raúl Porras Barrenechea, Los cronistas

del Perú (1528-1650, Lima: Sanmarti.

SARMIENTO de GAMBOA,

Pedro

1943 Historia

de los Incas [1572]. Edición revisada por Ángel Rosenblat. Buenos

Aires: Emecé Editores (Col. Hórreo).

ZÁRATE, Agustín

de

1995 Historia

del descubrimiento y conquista del Perú [1555]. Edición, estudio

preliminar y notas de Franklin Pease G.Y. y Teodoro Hampe Martínez. Lima:

Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, Fondo Editorial (Clásicos peruanos).

SECONDARY LITERATURE

ALONSO SAGASETA,

Alicia

1989 “Las momias de los incas: su función y

realidad social”, in Revista Española

de Antropología Americana (Madrid), vol. 19, p. 109-135.

ALZAMORA CASTRO,

Víctor

1963 Mi

hospital. Historia, tradiciones y anécdotas del Hospital Dos de Mayo.

Lima: Talls. Gráfs. P. L. Villanueva.

ASSADOURIAN, Carlos Sempat

1994 “La gran vejación y destruición de la

tierra: las guerras de sucesión y de conquista en el derrumbe de la población

indígena del Perú” [1987]. In Transiciones

hacia el sistema colonial andino, Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos,

p. 19-62.

BALLESTEROS GAIBROIS, Manuel

1963 Descubrimiento y conquista del Perú.

2001 “The Impact of Disease,” in George

Raudzens (ed.), Technology, Disease

and Colonial Conquests, Sixteenth to Eighteenth Centuries: Essays Reappraising the Guns and Germs

Theories. Leiden: Brill; pp. 127-166.

CASTELLI GONZÁLEZ,

Amalia

1981 “La primera imagen del Hospital Real de San

Andrés, a través de la visita de 1563”, in Historia

y Cultura (Lima), vol. 13/14, p. 207-216.

CASTRILLÓN VIZCARRA,

Alfonso

1999 La

destrucción de Cartago (novela).

COOK, Noble David

1998 Born

to Die. Disease and

DEZA, Luis, and BARRERA, Juan

2001 “Historia y leyenda acerca de los incas enterrados en el

Hospital San Andrés de Lima”, in Revista

de Neuro-psiquiatría (Lima), tomo 64, p. 18-35.

FARRINGTON,

1995 “The mummy, estate and

GARCÍA CÁCERES, Uriel

2001 “Los

microbios como protagonistas de la historia”, in Copé (Lima), vol. XI, n° 29, p. 7-12.

GUILLÉN GUILLÉN,

Edmundo

1983 “El enigma de las momias incas”, in Boletín de Lima (Lima), nº 28, p.

29-42.

HAMPE MARTÍNEZ,

Teodoro

1982

“Las momias de los incas en

Lima”, in Revista del Museo Nacional (Lima),

vol. 46, p. 405-418.

2000a “Salvemos la última

morada de los incas”, in El Comercio,

Lima, 6 de febrero (Editorial).

2000b “Riva Agüero y las momias de los incas”, in El Comercio, Lima, 23 de febrero

(Editorial).

HERNÁNDEZ, Max

1993 Memoria

del bien perdido. Conflicto, identidad y nostalgia en el Inca Garcilaso de la

Vega. Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos & Biblioteca Peruana de

Psicoanálisis.

HINOJOSA CUBA,

Carlos

JARQUE, Fietta

1998 Yo me perdono (novela). Madrid: Grupo Santillana (Extra

Alfaguara).

LASTRES, Juan B.

1954 “Historia de la viruela en el Perú”, in Salud y Bienestar Social (Lima), vol. 3.

LOHMANN VILLENA,

Guillermo

1957 El

corregidor de indios en el Perú bajo los Austrias. Madrid: Ediciones

Cultura Hispánica.

LOMBARDI ALMONACÍN,

Guido

1992 Autopsia

de una momia de la cultura Nasca: estudio paleopatológico. Tesis para

optar el título de Médico-Cirujano. Lima: Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia,

Facultad de Medicina.

LOREDO, Rafael

1955 “Vaca de Castro y la momia de Huayna

Cápac”, in El Comercio, Lima,

7 de julio (edición de la mañana), p. 2 & 4.

MIRÓ QUESADA S.,

Aurelio.

1971 El

Inca Garcilaso y otros estudios garcilasistas. Madrid: Ediciones

Cultura Hispánica.

PATRÓN, Pablo

1894 “La enfermedad mortal

de Huayna Capac”, in La Crónica Médica, Lima, 15 de junio, p. 179-183.

POLO, José Toribio

1877 “Momias de los incas”, in Manuel de

Odriozola (comp.), Documentos

literarios del Perú, Lima: Imprenta del Estado, tomo X, p. 371-378.

Porras

Barrenechea, Raul.

1986 Los Cronistas del Perú (1528-1650) y

otros Ensayos. Lima.

RABÍ

CHARA, Miguel

1999 Del

Hospital de Santa Ana (1549 a 1924) al Hospital Nacional Arzobispo Loayza (1925

a 1999). 450 años de protección de la salud de las personas. Lima:

Gráfica Fina (Historia de la medicina peruana, 2).

RIVA-AGÜERO, José de

la

1937 “El Perú de 1549 a 1564” [1922]. In Por la Verdad, la Tradición y la Patria (opúsculos), Lima:

Imprenta Torres Aguirre, Lima, tomo I, p. 3-67.

1966 “Sobre las momias de los Incas” [1938]. In Estudios de historia peruana. Las

civilizaciones primitivas y el Imperio Incaico, ed. César Pacheco

Vélez, Lima: Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú (Obras completas, tomo

V), p. 393-400.

ROSTWOROWSKI de DIEZ

CANSECO, María

1953 Pachacutec Inca Yupanqui. Lima: Imprenta Torres

Aguirre.

ZAVALA, Silvio

1978 El

servicio personal de los indios en el Perú (extractos del siglo XVI),

tomo I. México, DF: El Colegio de México.

|

Table

1. 19 Early Primary Sources Describing the Death of the Inca Huayna Capac |

||||

|

Year |

Author |

Death of Inca Huayna

Capac |

||

|

Year |

Description (with page number) |

Origin |

||

|

1533 |

Francisco

de Xerez |

1524 |

115: Atahualpa,

attributes death to "aquella enfermedad" |

|

|

c.1539 |

The anonymous

soldier (Cristóbal de Mena) |

|

138: “y Guaynacapa

se fué en jornada a Popayán, y de vuelta que volvió murió en Quito." |

|

|

1543 |

Pedro Sancho de la

Hoz |

|

Describes

mummy; cause of death not mentioned. |

|

|

1544 |

*Cristóbal Vaca de

Castro |

|

22: "se

estaba muriendo de la pestilencia de las viruelas” |

|

|

1550 |

*Pedro de Cieza de

León |

1527 |

200: "cuentan

que vino una gran pestilencia de viruelas tan contajiosa que murieron más de

dozientas mill ánimas” |

|

|

1557 |

Juan

de Betanzos |

1526 |

201:

An illness that took away his reason and understanding and gave him “sarna y

lepra”. |

|

|

c.1565 |

Alonso

Borregan |

|

84: “una

enfermedad que le dio muy recia que debia de ser perlesía” |

|

|

1572 |

*Pedro

Pizarro |

1521 |

181: “enfermó del mal de las viruelas … y murió

este Guainacapa.” |

|

|

1572 |

Pedro

Sarmiento de Gamboa |

1524 |

165:

An illness of fevers, although others say of smallpox and measles; Ninan

Cuyoche [his son] died of the pestilence of smallpox. |

|

|

1582 |

Fr.

Hernando Pablos |

|

270: “una

pestilencia muy grande en que murieron innumerable gente de un sarampión que

se abrían todos de una lepra incurable, de la cual murió este señor

Guainacapac” |

|

|

1586 |

Fr. Miguel Cabello

de Balboa |

1525 |

459: “y paró en

unas mortales calenturas y sintiendose cercano de la muerte hizo su

testamento” |

Cuzco |

|

1586 |

*Toribio

de Ortiguera |

|

355: “y murió el

dicho Guaynacapa de enfermedad de viruelas antes que los españoles le

pudiesen ver” |

|

|

1590 |

Martín

de Murúa |

|

135: “unos dicen

que murió [en Quito] de calenturas, y

otros dicen que habiendo gran pestilencia de viruelas en un pueblo llamado

Pisco” |

Cuzco |

|

1605 |

Padre Reginaldo de

Lizarraga |

|

516: “epidemia de

romadizo y dolor de costado que consumio la mayor parte de los indios” |

|

|

1613 |

El Inca Gracilazo

de la Vega |

|

264: “dióle una

enfermedad de calenturas, aunque otros dicen que de virguelas y sarampión.” |

|

|

1613 |

Juan de Santa Cruz

Pachacuti Yanqui |

|

252: “abía sido

pestilencia de sarampión, el Ynga, después se esconde en ella tapándose con

la misma piedra y allí muere.” |

Cuzco |

|

1615 |

*Felipe Guaman

Poma de Ayala |

|

108: “Enbía dios

su castigo: Pistelencia de saranpión y

birguelas muy grandícimas, entienpo de Guayna Capac Ynga, se murió muy mucha

gente y el Ynga.” |

|

|

1630 |

Fray Buenaventura

de Salinas y Córdova |

|

59: “Fue tanta la

melancolía de Huayna Capac en Quito, considerando, que le auian dicho los

agoreros y el Sacerdote, que les mandó que alli lo pusiesen a morir” |

|

|

1630 |

Fr.

Giovanni Anello Oliva |

1523 |

83: “le dio una

grave dolencia que los Indios llaman Uanti, y en nuestro romance bubas que le

quittó la vida” |

|

|

1653 |

*Fr.

Bernabé Cobo |

|

160: “dijo el Inca

que se moriría, y luego le dió el mal de las viruelas. Estando muy enfermo se murió.” |

|

|

*

= author attributes death of Inca Huayna Capac solely to smallpox. |

||||

|

Sources: Anello Oliva, Fr.

Giovanni. 1895 Historia del reino y provincias del Perú. Lima. Anon. [“The

anonymous soldier”]. 1934. Relación del sitio del Cusco y principio de las

guerras civiles del Perú hasta la muerte de Diego de Almagro, 1534-1539.

Lima. Authorship ascribed to Cristóbal

de Mena (Porras Barrenechea, Cronistas del Perú, 558.) Betanzos, Juan de.

1987. Suma y narración de los Incas, ed. María del Carmen Martín

Rubio. Madrid. Borregan, Alonso.

1948 Crónica de la conquista del Perú. Sevilla Cabello de Balboa,

Fr. Miguel. 1951 Miscelánea Antártica. Lima, 1951. Cieza de León,

Pedro de. 1985 Crónica del Perú: Segunda parte. Lima. Cobo, Fr. Bernabé.

1892 Historia del Nuevo Mundo. Sevilla. Lizarraga,

Reginaldo. 1905 Descripción breve de toda la tierra del Perú, tucumán, Río

de la Plata y Chile para el Excmo. Sr. Conde de Lemos y Andrada, presidente

del consejo real de Indias. Madrid. Murúa, Martín de.

1987 Historia general del Perú. Lima. Ortiguera, Toribio

de. 1968 Jornada del río Marañón. Madrid. Pablos, Fr.

Hernando. 1965 Relación que enbio a mandar su Magestad se hiziese desta

ciudad de Cuenca y de toda su provincia. Madrid. Pachacuti Yamqui,

Juan de Santa Cruz. 1873 Relación de antiguedades del Perú. London. Pizarro, Pedro.

1978 Relación del descubrimiento de los reinos del Perú. Lima. Poma de Ayala,

Felipe Guaman. 1936 Nueva crónica y buen gobierno. Paris. Salinas y Córdova,

Fray Buenaventura de. 1957 Memorial de las historias del nuevo mundo Pirú.

Lima. Sancho de la Hoz,

Pedro. 1917 Relación para S.M. de lo sucedido en la conquista y

pacificación de estas provincias de la Nueva Castilla y la calidad de la

tierra. Lima. Sarmiento de

Gamboa, Pedro. 1906 Historia de los Incas. Berlin. Vaca de Castro,

Cristóbal. 1934 Discurso sobre la descendencia y gobierno de los Incas. Lima. Vega, El Inca

Garcilaso de la. 1985 Los Comentarios reales de los Incas. Lima. Xerez, Francisco.

1534 Verdadera relación de la conquista del Perú y Provincia del Cuzco.

Sevilla. |

||||

|

Table 2. Inferring

Cause of Death of the Inca Huayna Capac: |

|

||||||||||||

|

Author |

First |

Cause |

*Polo |

*Lastres |

*Dobyns |

Hemming |

*Wachtel |

* |

Assadourian |

*Cook |

Guerra |

*Alchon |

|

|

Xerez |

1534 |

Aquella enfermedad |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

|

|

Anon. |

1917 |

Murió |

X |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

|

|

Sancho |

1543 |

(describes mummy) |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

|

|

*Vaca de Castro |

1934 |

Viruelas |

X |

Yes |

. |

. |

. |

. |

Yes |

. |

. |

. |

|

|

*Cieza de León |

1554 |

Viruelas |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

|

Betanzos |

1987 |

Sarna

y lepra |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

Yes |

Yes |

. |

|

|

Borregan |

1948 |

Perlesía |

X |

Yes |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

|

|

*Pizarro |

1842 |

Viruelas |

Yes |

Yes |

. |

. |

. |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

. |

|

|

Sarmiento

de Gamboa |

1906 |

Fevers |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

. |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

|

Pablos |

1965 |

Una lepra

incurable |

X |

X |

X |

Yes |

. |

. |

. |

|

. |

. |

|

|

Cabello de Balboa |

1951 |

Unas mortales

calenturas |

X |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

. |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

|

*Ortiguera |

1968 |

Viruelas |

X |

X |

X |

|

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

|

|

Murúa |

1925 |

Calenturas o

viruelas |

X |

. |

. |

Yes |

. |

Yes |

Yes |

. |

Yes |

. |

|

|

Lizarraga y Ovando |

1905 |

Romadizo y dolor

de costado |

Yes |

. |

Yes |

Yes |

. |

Yes |

. |

. |

Yes |

. |

|

|

Vega |

1613 |

Calenturas |

Yes |

Yes |

. |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

. |

Yes |

Yes |

|

|

Pachacuti Yamqui |

1873 |

Sarampión |

. |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

. |

Yes |

. |

Yes |

Yes |

|

|

*Poma de Ayala |

1936 |

Saranpión y

birguelas |

X |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

|

Salinas y Córdova |

1630 |

Melancolía |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

|

|

Anello

Oliva |

1895 |

Bubas |

. |

Yes |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

Yes. |

. |

|

|

*Cobo |

1892 |

Viruelas |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

. |

Yes |

Yes |

|

|

Total sources

cited |

6 |

11 |

7 |

10 |

5 |

9 |

10 |

6 |

12 |

7 |

|||

|

Sources

cited that mention smallpox |

3 |

5 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

3 |

4 |

3 |

|||

|

* = death of Inca Huayna Capac attributed

to smallpox ”X” = Secondary account published before

first publication of primary source and thus evidence could not have been

taken into consideration. Note:

Works must cite primary source directly to be tallied “Yes”. |

|

||||||||||||

|

Sources: Primary:

See Table 1. Secondary: Alchon, Suzanne Austin 2003 A Pest in

the Land: Assadourian, C. S 1994 “La gran vejación y

destruición de la tierra: las guerras de sucesión y de conquista en el

derrumbe de la población indígena del Perú,” in Transiciones hacia el

sistema colonial andino. Cook, Noble David 1998 Born to Die:

Disease and Crosby, Alfred W. 1972 The Columbian

Exchange: Biological and Cultural

Consequences of 1492. Dobyns, Henry F. 1963 "An Outline of

Andean Epidemic History to 1720," Bulletin of the History of Medicine

17:493-515. Hemming, John 1970 The Conquest of the

Incas. London. Lastres, Juan B 1954 Historia de la viruela en

el Perú. Lima. Polo, Jose Toribio 1913 "Apuntes sobre las

epidemias del Perú." Revista Histórica 5:50-109 Wachtel, Nathan 1971 La vision des vaincus:

Les Indiens de Pérou devant la conquête espagnole, 1530-1570. Paris. |

|

||||||||||||

|

Table

3. 33 Quechua Terms Related to Illness

in Three Early Dictionaries |

|||

|

Spanish |

Santo Tomas (1560) |

“Ricardo” (1586) |

Gonzalez Holguín (1608) |

|

Berruga (o peca de la cara) |

Moro, ticti o rimpicota; hacer - Moroyani |

Ticti |

Ticti;

hacerse verruga - tictiyan |

|

Bubas |

. |

Huanti,

huantictam onconi |

Tener – Huantictam vnconi huanti vncoytam vncconi huanti hapihuan, o vncuhuan |

|

Calenturas |

Rupay huncuy; con frío chucchu |

Rupay

oncoy; con frío chucchu; lenta chaquirupay oncoy |

Rupay vncuy; tener - Rupaytam vnconi o rupay vncoytam vnconi; |

|

Contagion |

|

Pahuac

oncoy |

Contagiosa dolencia – Ppahuak vnccoy ranticuk vnccuy |

|

Cundir

mancha |

Cundir, crecer poco a poco como mancha - Mizmini, gui |

Miranvisuin |

Mapa mirarin o mirarccun mizmirccun mizmirin |

|

Curar |

Cura

de enfermo – hambinin |

Hampini |

Hampini |

|

Dañar |

Dañoso

– guacllic |

huacllichini |

huakllichini

o huchallicuni |

|

Dolencia |

Huncuy |

Oncoy

nanay |

Vnccuy

nanacuy nanay |

|

Enfermar de calentura y frio |

. |

chucchuni |

Chuchuni

chucchuhuanmichucchum hapihuan chucchuymanchayani |

|

Enfermar

de la calentura |

. |

Rupaytam

onconi, rupay oncoytam onconi |

Rupaytam

vncconi rupay onccoytam vncconi rupaymi vnccohuan o hapihuan rupayman

michayani |

|

Enfermedad

de mancha |

|

. |

Muru

onccoy |

|

Enfermedad

mortal |

Huncuy,

o quixiay |

Huañuy

oncoy |

Huañuy hatun vnccoy o sullumantu hatun nanay |

|

Fluxo de sangre |

. |

Vsputay yahuarapay |

Cencca yahuar hamupayay sutuy vnccoy o vsputay |

|

Hambre |

Yarecay |

Yarecay, yarcay. |

Yareccay |

|

Infección |

. |

Inficionar

= rantini |

Inficionar a otro pegando sus pecados o enfermedad = Huchantam vnccoynintam rantiycun pahuachin |

|

Lepra |

Caracha |

Caracha

llecte |

Lluttasca llekte o lluttascca ccaracha |

|

Mal |

Manaalli |

Mana

alli |

Mana

allin |

|

Mal de viruelas o sarampion |

|

|

Muru vncoy |

|

Maltrato

|

. |

-ar

– quezachani |

Huchapac

mirachicuymichay |

|

Mancha

redondeada |

Muru |

Cundir

la mancha – visuin |

Manchar mas o cundir la mancha = Mapam mmizmirin mirarccun |

|

Mortandad |

. |

Huañuypacha |

|

|

Muerte |

Guñuy |

Huañuy |

Huañuy |

|

Muerto de hambre |

Micuimanta Guañusca |

Micuymantan

huañuni o huañusca |

Yarecaymanta

o micuymanta huañuni muchucuni huanacuni yarecaypa aparisccamcani huañuy

huañuytam yarecani yarecayapatihuan |

|

Peca

de la cara |

Moro |

Mirca |

Mirca |

|

Pegar

(enfermedad) |

. |

. |

Vnccoytam

rantiycupuni |

|

Perlesía |

. |

Chiriayoncoy |

Chirirayay vnccoy o çuçunca çuçunca vnccoy |

|

Pestilencia |

. |

Pahuac

oncoy |

P. mal pegajoso = ppahuak vncoy o rantiy rantiy, o ranticuk vnccoy |

|

Prevención |

|

Prevenirse – camaricuni, camarayani |

|

|

Remedio |

. |

-ar

allichant, yanapani |

Yachacupucuk; -ar allichapuni o yacha cuchipuni |

|

Romadizo |

Chulli |

Chulli |

Chulli |

|

Sarampion |

. |

Muru

oncoy |

Hatun

muru vncuy |

|

Sarna |

Çulpo; sarna tener – çulpuyani . gui.o |

Caracha |

Caracha; llecte caracha |

|

Viruelas |

. |

Muru oncoy |

Huchuy muru vncuy |

|

Table 4. Terms of Destruction and Decay in Early Quechua-Spanish

Dictionaries |

|||

|

Spanish |

Santo Tomas (1560) |

Ricardo (1586) |

Gonzalez Holguín (1608) |

|

Alboroto |

. |

Tacuricuy |

Tacuricuy |

|

Castigar |

Mochochini, gui |

Muchuchij |

Muchuchini mirani |

|

Codiciar |

Monapayani, gui |

Munani; codiciador munac,

munapayac |

Munarini munapayani

ñocapcanman ñini munapucuni |

|

Combate |

Aucanacuy |

-ir atinacuni |

-ir Atipanacuni auca nacuni |

|

Crueldades |

Ancha piñac; cruel cosa sin misercordia manacoyapayac |

Cruel = haucha |

Cruel = haucha |

|

Desbaratar |

D. Batalla – chicrichini.gui o atini gui |

Atini llasani; huacllichini |

D. en guerra - Huacllicachini |

|

Despoblado pueblo |

. |

Purumasca llacta |

Purumllacta o purumyascca llacta, culluk o kulluchisccallacta |

|

Despoblar, -ado |

Purumachini.gui, o purum |

Purum (yermo) |

Llactactanpurum yachini kulluchini cculluchircuni |

|

Destrozar en guerra |

. |

. |

Champircayani huancurcayani |

|

Empalar |

|

. |

Kazpiman çattini o Kazpicta

çattiycupuni |

|

Esclavo |

Pinas |

E. habido de guerra = Piñas |

E. habido de guerra = Piñas; E. comprado Rantiscaruna; E. hazer o captiuar – Piñaschani |

|

Fatiga |

Fatigar – llaquini, gui |

Llaquicuy puticuy |

Machitayay; Fatigar el cuerpo con trabajos – Huañuyta llamkachini o ñaccarichini |

|

Matanza |

. |

. |

Matar a muchos = huañu chircarini |

|

Melancolía |

|

. |

M. enfermedad Pputirayay huaccanayay vnccoy |

|

Osario |

|

Tullu taucasca colosca |

Tullu tauccascca ccotosca |

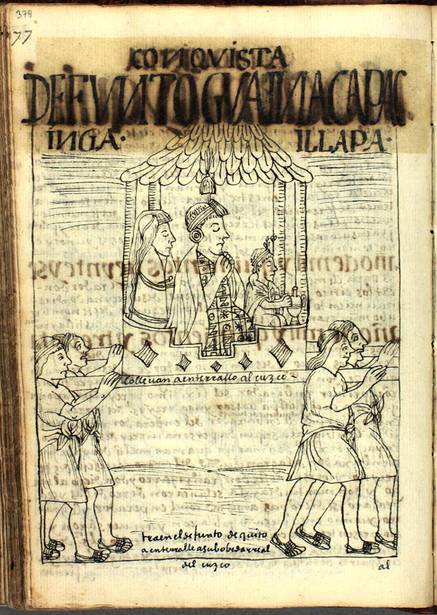

Figure 1. “379. The body of

Huayna Capac Inka,

being carried from

Note the absence of pockmarks on

the face of Huayna Capac’s mummy. The

beautifully crafted, realistic illustrations in this pictorial history of Early

Peru frequently depict tears and welts on the faces of individuals (for our

favorites, see pp. 219, 310, 453, 659, 879, 882, 888, 939, and 955), but Huayna

Capac’s face is wholly clear of marks of any kind.

Source:

Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, El primer Nueva corónica y buen

gobierno, http://www.kb.dk/elib/mss/poma/index-en.htm, p. 379.

Appendix

A. Results from Ground penetrating radar (GPR)

of the former Hospital Real de San Andres

Grid 12: Mark problems prevent effective 3D modeling and slicing in Radan, but

examination of the profiles reveals that the anomaly identified on the map is

in fact quite large (approximately 3 x 4m in area) but also relatively faint.

The top of the anomaly appears to be a subsurface stratum at approximately 50

ns in depth. A faint “X” signature – an indicator of reverberation – on several

of the profiles indicates that the pulses were bouncing between two geological

or architectural contacts. However, given the relative thinness of the anomaly

itself (approximately 10 ns) and the faintness of the “X” reverberation

signature, it is not thinkable this is a subsurface cavity on the order of what

our project is looking for. See illustration no. 1.

Grid 14: There is a large anomaly in the center of the grid

extending from about 20 to 35 ns in depth.

However, the photo indicates that this area was retiled at some

point. On the surface, two clear lines

of different tile correspond to sewer covers noted during data collection. These likely sewer pipes are shown below in a

2-ns-thick plan view at 10.5 ns depth and north at the top. Also note the center area of torn-up tile.

Then at 25 ns depth, the larger center anomaly is visible. Even if it is more

than just noise from the disturbed patio tile, the center anomaly may not be

associated with the more shallow diagonal sewer pipes. However, in sum, it

appears that this patio has seen extensive work in relatively recent times

(i.e., the twentieth century). See illustrations no. 2 and no. 3.

Grid 46: There is a large (3 x 3 m), roughly triangular zone of high reflection

at the north side of the grid. There are

two possible confounding factors, however; first, surface and near-surface

slices also show reflections in the same area, so the deeper one could be an

echo of this. Also, in profile the

anomaly is solid-looking in plan but in profile is made up mostly of “X”

signatures that could be oscillations between strata or walls. See illustration

no. 4 (48 ns depth, 1 ns thick, north at the bottom).

Grid 49: Extremely noisy profiles. The most promising anomaly noted is probably

the curved rock or brick surface (vault?) that was visible during collection.

It seems to reach approximately 2.5-3 m beneath the surface, although of course

the travel time assumptions for such an estimate are extremely shaky. See

illustration no. 5.

Grid 52: There is a large downward-curving surface with its apex at

approximately 75 ns or 3 m depth. In some profiles, wide “X” signatures are

visible beneath the curve, centered around 100 ns. This depth is near the limit of this unit’s

capabilities; the strength of the X reflection despite the weakness of the

signal may indicate an open space (crypt?) beneath the curved surface. In the

profile shown at illustration no. 6, the apparent column or shaft of high

reflection is an artifact of ringing near the surface. However, even this

ringing is perhaps a good sign, as it occurs precisely beneath the engraved

marble slab noted during data collection. Small but very well-defined “X”s

beneath the slab (not visible on the illustration) indicate that it probably

covers an open shaft.

The main body of the “crypt” measures approximately 15 x 8 x 1.5 m. Its

apparent truncation at the east end of the chapel could be due to the change in

floor material from mosaic to large tiles. The apparent greater depth of the

“crypt” feature on the western end is due in part to the column of oscillating

reflections from the marble slab’s underside. However, even given this caveat,

it is clear that there is a very large feature beneath the chapel floor,

beginning at a depth (75 ns) considerably below 50 ns, the level at which a

plane of high reflection (possibly bedrock) occurs in many other grids. See

illustrations no. 7 and no. 8.

QUALITATIVE

TABLE FROM THE GPR SURVEY

|

Grid |

Rating |

Grid |

Rating |

Grid |

Rating |

|

1 |

1 |

21 |

5 |

41 |

5 |

|

2 |

5 |

22 |

4 |

42 |

5 |

|

3 |

4 |

23 |

5 |

43 |

5 |

|

4 |

4 |

24 |

4 |

44 |

4 |

|

5 |

5 |

25 |

5 |

45 |

5 |

|

6 |

5 |

26 |

5 |

46 |

2 |

|

7 |

5 |

27 |

5 |

47 |

5 |

|

8 |

5 |

28 |

5 |

48 |

4 |

|

9 |

5 |

29 |

5 |

49 |

2 |

|

10 |

5 |

30 |

5 |

50 |

5 |

|

11 |

5 |

31 |

5 |

51 |

3 |

|

12 |

3 |

32 |

5 |

52 |

1 |

|

13 |

4 |

33 |

5 |

|

|

|

14 |

3 |

34 |

4 |

|

|

|

15 |

5 |

35 |

5 |

|

|

|

16 |

5 |

36 |

4 |

|

|

|

17 |

5 |

37 |

5 |

|

|

|

18 |

5 |

38 |

5 |

|

|

|

19 |

5 |

39 |

5 |

|

|

|

20 |

4 |

40 |

5 |

|

|

Appendix

B. The Death of the Inca Huayna Capac

according to Juan de Betanzos, Suma y

narración de los Incas, ed. María del Carmen Martín

Rubio (Madrid: Ediciones Atlas, 1987), 200-201.

estúvose en la ciudad del Quito

holgándose y recreándose bien ansi como se holgaban en la

ciudad del Cuzco seis años en fin de los cuales que en el Quito estuvo le dio

una enfermedad la cual enfermedad le quitó el juicio y entendimiento y dióle

una sarna y lepra que le puso muy debilitado y viéndole los señores tan al cabo

entraron a él pareciéndoles que estaba un poco en su juicio y pidiéronle que nombrase

señor pues estaba tal al cabo de sus días a los cuales dijo que nombraba por

señor a su hijo Ninancuyochi el cual había un mes que había nacido y estaba en

los Cañares y viendo los señores que aquel tan niño nombraba vieron vieron

[sic] que no estaba en su juicio natural y dejárosle y saliéronse y enviaron

luego por el niño Ninancuyochi que había nombrado por señor y otro día tornaron

a entrar a él y preguntárosle de nuevo que a quién dejaba y nombraba por señor

y respondióles que nombraba por señor a Atagualpa su hijo no acordándose que el

día antes había nombrado al niño ya nombrado y luego los señores fueron al

aposento do Atagualpa estaba al cual dijeron que era señor y reverenciárosle

como a tal el cual dijo que él no lo quería ser aunque su padre le hubiese

nombrado y otro día tornaron los señores a Guayna Capac y viendo que Atagualpa

no quería serlo y sin le decir cosa del otro día pasado y pidiéronle que

nombrase señor y díjoles que lo fuese Guascar su hijo… después de haber

nombrado al Guascar en la manera ya dicha por señor dende a cuatro días expiró

y luego que acabó de expirar volvieron los mensajeros que habían ido por el

niño que había nombrado por señor Guayna Capac el cual habían hallado muerto

que aquel día que llegaron había muerto de la misma enfermedad de Lepra como su

Padre y dende a poco que llegaron estos mensajeros llegaron otros mensajeros

que enviaban los caciques de Tumbez a Guayna Capac por los cuales mensajeros le

hacían saber como habían llegado al puerto de Tumbez unas gentes blancas…

Guayna Capac el cual como falleciese los señores que con él estaban le hicieron

abrir y toda su carne sacar aderezándole porque no se dañase sin le quebrar

hueso ninguno le aderezaron y curaron al sol y al aire y después de seco y

curado vistiéronle de ropas preciadas y pusiéronle en unas andas ricas y bien

aderezadas de pluma y oro y estando ya el cuerpo ansi enviárosle al Cuzco con

el cual cuerpo fueron todos los demás señores que allí estaban …

Lastres, 1957:

De todas maneras es necesario decir

que en el quechua o runa simi,

existe la voz muru; y la combinada muru onccoy o enfermedad de mancha, que

puede identificar la viruela, como otros procesos exantemáticos. Los cronistas Pedro Pizarro, Miguel Cabello

Balboa, Antonio de Herrera, Garcilaso Inca, Borregán, Santa Cruz Pachacuti

Yamqui, Sarmiento de Gamboa, Cieza de León, Huamán Poma de Ayala, Anello Oliva,

y los médicos Paredes, Olano, Tello y Arcos, se han ocupado extensamente de

este delicado problema de paleo-patología, abogando por diversos

diagnósticos. Los más opinan por la

viruela, algunos por el tifus exantemático, y otros por el paludismo o la