|

The |

|

Evan Roberts, Steven Ruggles, Lisa Y Dillon, |

![]()

|

Full Text (6072 words) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Copyright HELDREF

PUBLICATIONS Spring 2003

The North Atlantic

Population Project (NAPP) brings together late-nineteenth-century

complete-count census microdata from This article provides

a brief history of the project, a discussion of the main issues involved in

creating the database, and an overview of methodological and research

opportunities the completed database will provide scholars. Occupational classification

is the most complex and time-consuming aspect of the project and has received

much of our attention so far. The major issues in classifying occupations in

the NAPP database are discussed in a companion article by Roberts et al. (pp.

89-96 in Part Two of this issue). Background The NAPP will

incorporate complete, machine-readable versions of late-nineteenth-century

population censuses of The NAPP is made

possible by the availability of complete machine-readable transcriptions of

nineteenth-century census enumerators' manuscripts. The Church of Jesus

Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS), in collaboration with local genealogical

societies, laboriously transcribed and entered into databases the 1881

censuses for In In 2000, participants

from each country met in Collaborators The NAPP is a

collaborative project composed of research teams from each of the five

countries included in the database. These five countries are fortunate to

have extraordinarily rich collections of surviving individual-level census

data, as shown in table 1. The

The NAPP database will

include the seven censuses marked as "N" in table 1: it will

combine the three LDS-transcribed censuses of Great Britain, Canada, and the

United States with two censuses each from Iceland and Norway.6 National

research teams have prepared-or are in the process of preparing-these data

for public use. The NAPP collaborators have pieced together funding for data

preparation from numerous sponsors to support the painstaking tasks of data

cleaning and coding. This project does not fund these basic data preparation

activities; rather, it is intended to coordinate those activities to produce

a harmonized database. The NAPP involves researchers

from the Universities of Montreal and Ottawa in Canada, the University of

Essex in Great Britain, Statistics Iceland, the Universities of Bergen and

Tromso in Norway, and the University of Minnesota in the United States. Each

of the research teams brings extensive experience with large-scale

nineteenth-century census data; most of the participants are key researchers

on projects to create microdata samples and complete-count data sets listed

in table 1.7 Coordinating work in five countries on two continents is

challenging. We communicate extensively through Web-based tools, e-mail,

telephone, and annual meetings of all collaborators. The first two

meetings-held in Minneapolis in November 2001 and in Grundarfjor[eth]ur,

Iceland, in October 2002-focused on developing common coding schemes for

occupations and other key variables. It can also be difficult to reach

agreement when a large group is concerned, but the collaboration is guided by

the philosophy that decisions should be reached by consensus and if that is

not possible, then a majority decision is required. Harmonizing the NAPP

Database Harmonization of these

North Atlantic censuses is eased because of a high degree of comparability in

the original enumeration processes across countries. This comparability was

due primarily to the formal as well as informal collaboration of North

American and European statisticians and to the development of international

standards in forums such as the International Statistical Congress and the

International Statistical Institute. For example, Joseph Kennedy, the United

States census superintendent, became a national statistical expert in part

through his interactions with European statisticians (Anderson 1988, 46, 60).

Enumeration practices in the United States as well as across the Atlantic

informed the design of the nineteenth-century Canadian censuses (Curtis 1994,

2000; Worton 1998).

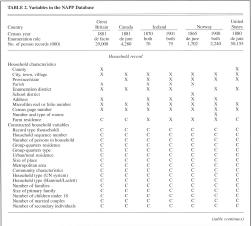

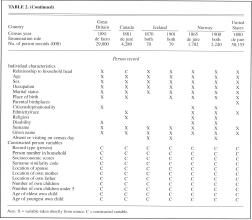

Table 2 describes the

data files to be included in the North Atlantic database. With respect to

their structure, organization, and available information, the seven censuses

are remarkably comparable. Each census enumerated individuals, and in each

case, those individuals are grouped into households, which were defined in

similar terms in each country. All countries defined a household as "a

group of people sharing a common place of residence." There is a core

set of variables common to virtually all data sets, including relationship of

each individual to the household head, age, sex, marital status, occupation,

and birthplace. Geographical precision for place of residence varies across

countries, but it is possible to identify all places with populations over

5,000 for each country. Across the five countries, we identify approximately

25,000 communities. These common core variables will allow us to construct a

variety of new variables describing community and neighborhood

characteristics, household composition, socioeconomic status, and family

interrelationships.

Most of the censuses

were taken on a de jure basis, under which individuals who were temporarily

absent from home-such as migrant workers and travelers-were to be enumerated

at their usual place of residence. The exception is the British census, taken

under a de facto rule, which specified that no one who was present on census

night at a particular address could be left out of the tally and that no

person absent from home could be written in. From 1870 onward, persons in

Norway and Iceland were to be enumerated both at their usual place of

residence and at the place they stayed on census day, and enumerators

identified both temporary visitors and absent household members. These

variations in enumeration rules pose only minor compatibility problems, but

investigators of some household composition and migration issues will have to

be aware of them. There are two main

tasks necessary to create the harmonized NAPP database. First, we must

develop common classification systems for occupation, birthplace, family

relationship, and group-quarters type that balance the goals of international

comparability, retention of detail, and ease of use. Second, we must build a

consistent set of constructed variables describing household composition,

family interrelationships, urban and metropolitan residence, and other

geographic characteristics. The most challenging

task is the development of harmonized coding systems to allow comparison

across countries. At present, much of the data arc in the form of alphabetic

character strings, representing the transcription from the original source

material. These strings are too unwieldy for statistical analysis; to make

the data usable, we must develop numeric codes for each variable. For

variables such as age, sex, marital status, and religion, this process is

straight-forward, because the variation in values for these variables across

countries is not great. Other variables are more complicated; for example, we

estimate that there are unique strings for 2 million occupations, 1 million

birthplaces, and 30,000 family relationships. To translate from

character strings into numeric codes, we must construct data dictionaries

that assign a numeric code to each alphabetic variation that occurs in the

data. This work is difficult enough in the context of a single country; for a

project of this scale, it requires a team of expert coders working in close

cooperation, sharing coding decisions continuously. We have created a set of

merged dictionaries of unprecedented scale that include the alphabetic

strings from 90 million persons in all five countries. This is uncharted

territory. Until recently, constructing such a dictionary would have

necessitated assembling experts with appropriate language skills and

historical knowledge about each country in a single location, a prohibitively

expensive task. Using Internet technology, however, we are able to distribute

the task, thus working on the dictionaries in multiple countries

simultaneously. For a description of this coding process for occupation, the

most complicated variable, see the Roberts et al. companion article (pp.

89-96 in Part Two of this issue). When feasible, the

coding is compatible with the IPUMS-USA and IPUMS-International coding

systems. We also follow the same IPUMS principle of retaining detail while

providing harmonized codes suitable for comparative research. Composite

coding systems allow us to provide information available across all censuses

in a least-common-denominator code and information unique to one country (or

set of countries) in a subsequent "detail" code. We also preserve

country-specific variables with information or coding systems unique to a

particular country; these include, for example, religion (only available in

Canada and Norway) and occupations coded to the 1881 British classification

scheme. This sensitivity to the particular conventions of each country's data

is important for maintaining productive collaboration and will maximize the

usefulness of the finished database. In addition, researchers will be able to

download the raw data and analyze, replicate, or alter the coding systems

applied by the NAPP team. We will create a

number of constructed variables to facilitate the analysis of household

composition, family interrelationships, and own-child fertility. These

household- and person-level variables are detailed in table 2. Among the most

important of these are pointer variables that indicate the location within

each household of each individual's own spouse, mother, and father, as well

as number of own children.8 These pointer variables allow researchers to

attach the characteristics of immediate kin (spouse's birthplace, father's

occupation, children's characteristics, etc.) without the need to resort to

programming (Ruggles 1995). We will add the variables required for basic

own-child fertility analysis: number of own children present, number under 5

years of age, age of eldest child, and age of youngest child. We also plan to

construct a set of variables to describe the composition of families and

households, replicating the most commonly used historical and contemporary

classification systems, as well as household characteristics such as the

number of persons, families, children, married couples, and servants in each

household. Finally, we will create technical variables to aid in data

management and analysis, such as record type, serial number, and

group-quarters residence. Documenting and

Disseminating the NAPP Database In addition to data preparation, the project

involves documenting the comparability of census enumeration instructions,

procedures, and definitions across the five countries, creating

machine-understandable metadata compliant with the Data Documentation

Initiative (DDI) metadata standard, and developing efficient Web-based

software to optimize and simplify access to the entire database. The creation of

integrated documentation is central to the project, and the development of

these materials will be a collaborative enterprise. We are working on

comprehensive documentation for each of the censuses in the database,

including facsimiles of census forms and enumerator instructions. When the

original documentation is in another language, we plan to translate the most

essential material into English. When foreign-language material is extensive,

however, we will provide the full text in the original language with a brief

English-language translation. The documentation system will also describe all

procedures undertaken to generate the harmonized database, including the

actual computer code, data dictionaries, and a textual description of the

data manipulation process. All documentation will be compliant with the DDI

metadata standard (see Block and Thomas, pp. 97-101 in Part Two of this

issue). Few users will be

interested in analyzing the entire data set of 90 million cases. Therefore,

we will disseminate the database through a data extraction system that

integrates access to metadata and microdata and allows users to carry out

substantial manipulation of the data. The data access system for the North

Atlantic database will be based on a similar system currently under

development as part of the IPUMS-International project (see Ruggles et al., pp.

60-65 in Part Two of this issue). Web sites in Great Britain, Canada, Norway,

and the United States will mirror the NAPP data access system and provide

unrestricted access for academic researchers. Applications for

Complete-Count Data The availability of information

on entire populations will open important new avenues of research. The

following discussion describes some new methodological approaches that will

be possible with complete-count data. Study of small

dispersed population subgroups. Many small population subgroups-defined by

race, ethnicity, occupation, or even age-can be studied only with very high

density data sets. For example, the availability of complete-count data will

allow the study of the indigenous populations of Canada, Norway, and the

United States. The 1881 Canadian census microdata include over 60,000

aboriginal persons; these cases would include sufficient indigenous women of

childbearing age to allow in-depth fertility analysis. Similarly, existing

sample data are inadequate to study immigrant groups in detail. A substantial

proportion of the Icelandic population emigrated to Canada and the United

States, but there are insufficient Icelandic cases in any of the existing

samples to allow quantitative analysis. This is also true for the Irish

population in England. The number of Norwegians in North America is larger,

but there are still not enough for detailed analysis using a sample database.

The new database will also allow, for the first time, comparative study of

particular age groups such as centenarians. It will also have adequate cases

to compare specific occupations (e.g., sailors, fishermen, and sons of

farmers) across all five nations. Community studies. The

community study has been one of the most fruitful analytical approaches in

both history and sociology. Most sample data lack sufficient cases to enable

researchers to examine particular localities. Because the new database

includes the entire population, it will allow scholars to extract customized

data sets focusing on particular communities. The international dimension of

the database will allow investigators to undertake comparative community

studies. For example, researchers could compare patterns in a Minnesota

Norwegian community with the sending community in Norway. Investigators could

also examine cross-border Canadian-U.S. or English-Scottish communities, to

compare economic and social patterns in neighboring areas distinguished only

by political and institutional structures. There is a large demand for local

historical statistical data, and the North Atlantic database will immediately

become an essential tool for community historians of all sorts. Detailed

personal identifiers for individuals-including full name, age, sex,

occupation, marital status, and birthplace-create the potential for

researchers to link NAPP data with other contemporaneous sources of basic

demographic information, such as ship lists, school and college attendance

records, friendly society (benefit-society) membership lists, as well as

birth, death, marriage, and emigration registers. Even historians who make

little use of quantitative analysis will be able to quickly and painlessly

locate their study subjects in the manuscript census. Longitudinal analysis.

Perhaps the greatest limitation of the existing samples is that they are

cross-sectional snapshots and do not allow one to trace individuals across

time. This problem will be alleviated by the new database. As shown in table

1, for each country there are machine-readable samples or complete-count data

sets for multiple years. Thus, it will be possible to create a series of

linked samples; in the case of Canada, for example, individuals in the 1871,

1891, and 1901 census samples can be linked with the complete-count 1881

census. Thus, researchers will be able to construct three linked Canadian

samples, covering 1871-1881, 1881-1891, and 1881-1901. In Norway, Iceland,

and Great Britain-where there are multiple complete censuses-there is

potential to link individuals across more than a single pair of census years.

Researchers will even be able to link some individuals across countries; for

example, from Norway in 1865 to Canada in 1881 and back to Norway in 1900. Linked census data

hold the promise of finally resolving some of the longest-running debates in

nineteenth-century social history. Past studies of social and geographic

mobility were not entirely conclusive because of their exclusion of migrants

and their small sample size. Scholars will be able to gauge the extent of

social and geographic mobility, analyze the interrelationship of geographic

and economic movement, and assess trends and differentials in social mobility

far more reliably than heretofore (Thorvaldsen 1995). In addition, the linked

samples will allow investigation of questions regarding family formation and

dissolution. For example, they will allow scholars to answer several

controversial questions surrounding the formation of multigenerational

households in the nineteenth century (Ruggles 1994, 2001). Multilevel analysis.

In recent years, analyses of the effects of local context on individual

behavior have proven exceedingly valuable tools for research in historical

sociology (see Elman 1998; Kramarow 1995; Ruggles 1997a, 1997b). New methods

of multilevel analysis will increase the effectiveness of this approach

(DiPrete and Forristal 1994). A key problem for such nineteenth-century

research, however, is that the method requires independent variables

tabulated for small geographic units, and such data are scarce before the

twentieth century. The new North Atlantic database will allow creation of a

wide variety of contextual variables-such as racial or ethnic composition,

female labor-force participation, and occupational structure-at many

geographic levels, including the neighborhood and the enumeration district. Geographic information

systems. Geographer's are ordinarily unable to tap the power of microdata.

The existing nineteenth-century microdata files are samples, so when they are

used for small areas they provide insufficient precision for reliable

mapping. Although some relatively high density samples are available for the

period since 1970, those microdata files suppress detailed geographic data.

Therefore, geographers are forced to rely on complete-count aggregate data

that usually provide only basic summary statistics for small areas. The North Atlantic

census database will provide full geographic detail for every individual in

the population. Digitized small-area boundary files are already available for

Great Britain in 1881 and are in preparation for nineteenth-century Canada,

Norway, and the United States (Gregory and Southall 1998; Thorvaldsen 1997;

see also Fitch and Ruggles, pp. 41-51 in Part One of this issue).9 Therefore,

a large scholarly investment in nineteenth-century geographic information

systems already exists. What is lacking is a fine level of geographic detail

in social, economic, and demographic characteristics. The North Atlantic

census database will allow scholars to marry existing geographic boundary files

to population characteristics, thus creating a powerful new analytic tool.

Such fine geographic analysis will be especially potent in the analysis of

topics such as early suburban development and racial and ethnic residential

segregation (see, for example, Gardner 1998). Substantive research

areas. A cross-section encompassing the entire population of the North

Atlantic world in the late nineteenth century will address many of the major

themes of history, economics, demography, and sociology. The following four

examples describe some of these key substantive issues: 1. The North Atlantic

database will allow in-depth analysis of the processes of industrialization.

The first Industrial Revolution may have begun in rural England, but by the

late nineteenth century the entire North Atlantic world was involved in

manufacturing, production of raw materials, or both. The North Atlantic

database will allow unprecedented opportunities to explore economic

structures within and between each nation during this critical transitional

period. For the first time, we will have consistently coded individual-level

occupational data available for nineteenth-century censuses from multiple

countries. This will allow comparative analysis at the level of persons,

families, communities, or regions, as well as allow investigation of the

geographic organization of economic activity. Thus, the NAPP database will

allow scholars to address international and North American regional

differences in the scale and location of manufacturing activity, comparing,

for example, the distribution of particular industrial workers in large urban

centers versus smaller towns and villages. 2. The database will

also contribute to understanding of the fertility transition. At the time

these censuses were taken, each of the North Atlantic countries was

witnessing the impact of widespread deliberate fertility limitation.10 The

North Atlantic database will allow study of differential fertility patterns

in this critical period of demographic transition, to assess the importance

of such factors as occupational class, ethnicity, region, literacy, local

economy, size of locality, and family structures. Past comparative analyses

of the European fertility transition have relied on national-, regional-, or

parish-level aggregate vital statistics (Coale and Watkins 1986). This

approach has two major disadvantages. First, aggregate vital statistics do

not allow direct measures of child spacing or stopping behavior; only the

level of fertility can be considered. Second, the aggregate approach does not

allow control of individual-level socioeconomic characteristics. Study of

this elemental shift in population structure has the potential to enhance our

understanding of ongoing demographic change in the contemporary developing world

(Woods 2000). 3. Research on the

family will also benefit from the common set of constructed variables in the

NAPP database. These variables aid in the analysis of family and household

composition and will thus allow consistent comparisons across all five

countries. It will enable investigators to assess the impact of local context

on family systems through multilevel analysis and so for the first time

permit analysis of the effects of individual-level factors, local economic

conditions, regional inheritance systems, and national characteristics on the

nineteenth-century family. 4. Finally, the North

Atlantic database will constitute an outstanding resource for the study of

migration history. It will allow close and consistent comparisons of

occupational structure, marriage patterns, fertility, and family composition.

Researchers will be able to identify and compare specific sending and

receiving communities. In some instances, it will even be possible to follow

individual migrants across the Atlantic and back again. The NAPP database

will also facilitate the study of cross-border populations.11 In combination

with new machine-readable ship lists and emigration registers, the database

will open a new window on the implications of international population flows. Conclusion This article has

outlined the ongoing project to create the North Atlantic Population Project

database. Capitalizing on three decades of experience in creating census

samples, the NAPP applies them to a complete-count database including data

from five nations. Harmonizing five databases of this scale poses a range of

methodological and practical challenges. The potential payoff, however, is

great; we are confident that the twin benefits of complete-count data and the

ability to compare countries will have substantial benefits for social

science research. The NAPP will be compatible with existing and forthcoming

time-series of census data for all those countries contributing data. We hope

it will spur future efforts to increase the sample density of existing census

samples and promote comparative and transnational research.

|

|

|

Reproduced with

permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction or distribution is

prohibited without permission.

|

Subjects: |

|

|

Locations: |

|

|

Article types: |

Feature |

|

ISSN/ISBN: |

01615440 |

|

Text Word Count |

6072 |

|

|

|