September 1, 2010

I encourage "that clicking sound"

In a really good discussion of how technology has altered historical research David Turner writes

My only complaint, and I don't know if this is a complaint to be aimed at the camera manufacturers or the historians, is that I wish that there wasn't such a loud clicking sound when cameras take photos.

He's right that most digital camera users at the archives could eliminate that clicking sound. Digital compact cameras have the clicking sound merely to replicate the aural experience of a "real camera". Digital SLRs (and film SLRs, though how many people do archival photography with film?!) have to make that clicking sound. It's the sound of the shutter opening and closing to expose the sensor (or film) to light.

My most popular post on this blog has been Amateur Digitization for Historians, and I would now add one further variable to that discussion about digital compacts versus SLRs in the archives.

By way of background most archives don't allow flash (protecting the documents and protecting you from flash glare on glossy paper obscuring your images), and some archives don't allow copy stands, tripods and other stabilizing equipment. So a big concern in the archives is taking sharp photographs in low light holding your camera by hand.

Digital compacts typically use very high f-stop values which means your typical photo from a digital compact is sharper across the whole image with a wide depth of field. The foreground, center and background are all close to being in focus. But a high f-stop is not great in lower light (even room light), so many digital compact photos from archives without flash come out slightly blurry.

By contrast a digital SLR allows much lower f-stops than compacts. Now, with a lower f-stop your depth of field is reduced, but this doesn't matter as much in typical archival situations. Most parts of the paper are the same distance from the lens. SLRs also allow the user to set a very high ISO. This means you can compensate for the lack of light. Whereas a high ISO on film used to give you a very grainy image, digital SLRs give a much greater range of usable ISO values.

So, the short version of my advice is that if you can't use a stabilizing device, consider using an SLR for archival photography. You will lose many fewer photographs to being blurry than with a digital compact.

Another non-trivial advantage of the digital SLR is that it is much quicker. On a digital compact I find I can take about 400 photos an hour in the archives (mindlessly flipping from page to page). With a digital SLR I have taken over 1000 photos in an hour.

I think Turner's right that laptops, digital photography, and digitization of text are making fundamental changes to the practice of being an historian. My senior thesis advisor told me in the mid-1990s that how we do history hadn't changed much since Ranke or Beatrice and Sidney Webb (who wrote a great book about social and historical research). People looked at documents with their own eyes, and took notes. Then they analyzed and wrote about what they'd seen. Distance was a barrier to archival research. To be sure, the writing became quicker with the introduction of word processors in the 1980s, and computerized archival and library catalogs meant searching for sources was easier. But the process of primary historical research with old documents has been transformed in the last decade. Distance is less of a barrier to historical research, and the productivity of historians will increase tremendously as we take fuller advantage of the new technologies.

May 13, 2010

But now they can create a variable for overly_sensitive and dont_understand

This story is a doozy for academics (chronicle of higher ed version, sub required). Two business school professors sent a fake email to 6300 professors purporting to be from a prospective PhD student, with different versions of the email asking for an appointment now (today) or later (a week away). Different versions of the email also varied the apparent race and gender of the student.

Deception in the name of research. It's been done before and will be done again. A really important question is whether the impact on the deceived is outweighed by the scientific benefit of obtaining possibly better estimates of what people think and do. It's all very well for an historian to say "Involving colleagues, or any human beings, in a study without their knowledge and their prior consent is unethical," because historians rarely face this issue. Historians who use social science research so often delegate the dirty business of data collection to people long before us.

I happen to think that this kind of field experiment (it's not really survey research as some people think) is necessary. In the first instance there's the research done by sociologists and economists about racial and gender discrimination in housing and labor markets. You can't do this without deception, and there is to me a clear greater good in knowing the extent of discrimination in society.

But a more abstract and important question is how does measurement affect behavior? People say different things in surveys than they subconsciously reveal in laboratory experiments. But even in laboratory experiments people know they are being studied, and it's quite likely there's some kind of impact on their behavior in that setting. So field experiments where people don't know they're being studied, and might be [nearly] harmlessly manipulated are necessary to work out how people respond in different situations. Research involving deception has inherent risks, but that's a reason to monitor it closely and make sure the consequences for the deceived participants are low, not to never do it.

December 21, 2009

A tutorial (discussion section) attendance policy that worked (for me)

Tutorials (discussion sections, but referred to as tutorials throughout because it's shorter) are an important part of university education. Done well, students come away knowing and understanding a topic. Also, students make friends in this form of class. This is a non-trivial benefit. Done badly, they are excruciating in their silence and stupidity, and make a Catholic mass seem short. I refer here to discussions in the humanities and social sciences rather than focused problem-set oriented classes in sciences. The format is often that students have read some documents, perhaps a whole book (at graduate level), or some articles or chapters at undergraduate level. Questions about the readings are posed, and discussion is meant to ensue. But that discussion doesn't always happen in practice.

Done well the students get a great deal of benefit from preparing for the tutorial, and then add to that with their peers' contributions and different perspectives. A large part of the success of a good tutorial comes from a critical mass of prepared students who show up. The question is how to motivate good preparation and high attendance, while also respecting that university students are young adults who can make their own good or bad choices about whether to show up or not.

There are many models for how to motivate preparation and attendance. But I was not satisfied with policies I'd used previously. For example, many of my colleagues in New Zealand have a policy of requiring attendance at 8/11 tutorials during a semester. Missing more than 3 tutorials means that students have not met "mandatory course requirements," and are not permitted to complete the class. It's not uncommon in American colleges for 5-20% of the class grade to be for "participation and attendance."

What I tried this year in my second year (sophomore) social history class was the following policy for motivating preparation and attendance. It worked well.

- There were 10 tutorial sessions in the (12 week) semester, and a final week of student presentations in lecture and tutorial time.

- Five of the 10 tutorials (labeled "starred" tutorials) and the week of presentations had penalties for non-attendance

- Attendance was recorded at the starred tutorials by students submitting at least half a page of notes on the week's readings (1-3 journal articles or chapters, 30-60 pages of reading)

- Non-attendance was penalized with the following deductions from the final mark

- 1st missed tutorial/presentation: 4%

- 2nd missed tutorial/presentation: 8%

- 3rd missed tutorial/presentation: 16%

- 4th missed tutorial/presentation: 32% (highly likely fail)

- 5th and subsequent missed tutorial/presentation: 64% (definite fail)

- Students were encouraged to be responsible about letting me know if they could not make a tutorial for a legitimate reason (sickness, other university event clashing), and that if they handed in their notes they would not have marks deducted.

It looks way more complicated than it really was. Since it was a policy that differed from the standard ones in our department (and cognate departments in the humanities and social sciences) there were some questions about it. But the students understood it without any problems.

With this policy, 27 of a class of 31 did not lose any marks. In other words, 90% of the class attended (or demonstrated their preparation if sick or otherwise legitimately absent) for all the tutorials they were responsible for coming to. One student lost 4% and another 8%. Two students failed after missing 4 tutorials.

So, the policy had a very beneficial impact on student attendance. Most students prepared for class by taking more notes than required, and class discussions went very well as a result.

The policy seemed to work well for the following inter-related reasons

- I eliminated the common "mandatory course requirement" of (x-3) out of x tutorials that just permits absences from 3 tutorials. These absences are often concentrated around the deadlines for other classes, and especially at the end of semester. Students are busy and they reasonably prioritize things that are graded, or are fun. Wishing they loved learning more, and exhorting them to do so, just leads to disappointment.

- The sharp break in the "mandatory course requirements" approach between the penalties for missing 3 and missing 4 tutorials is unfair, and not well designed to motivate consistent preparation and attendance.

- The severe level of the penalties for frequent absences got students' attention, as it meant failing

- The policy did not require me to grade participation per se. The burden on me in implementing the scheme was minimal (less than 5 minutes per class to scan the notes that were submitted and record who didn't submit notes).

- A realistically small level of notes submitted for attendance (half page) was meant to achieve two goals

- It was meant to be, and was, seen as a realistic amount for students to achieve.

- I also encouraged the students to try and be concise in their note-taking, developing the skills of summarizing an article in a few lines -- that sometimes less is better for them. It was much nicer being able to tell students that they had somewhat over-prepared and discuss how they could do less work (but more effective!) next time.

- I did not try to compel perfect attendance, but designated some tutorials as more important than others. 6 weeks in which attendance was rewarded seemed to strike the right balance between encouraging work on this class, and recognizing that there can't be something due every week. The "starred" tutorials were mostly in alternating weeks.

- In the alternate weeks I ran practical workshops to help students with their research for the class. These were sometimes structured (worksheets on various aspects of the research), and sometimes an open computer lab. Clearly, not every class would need computer labs. The general idea was to do a more practical session where the success of the session did not rely as much on student preparation or attendance.

- In practice (this being the winter of the swine flu) I was understanding of student absences, when notes were submitted. Students seemed to view the policy as reasonable. The policy did the work of motivating students to prepare. I did not have to exhort students to do the reading and prepare for class because there was an objective penalty for not doing it. This freed up my emotional energy for more important things in the class.

The policy seemed to have a positive effect on classroom relationships, as well as motivating preparation and attendance. The awful tutorials where people attend without having done the reading, and the discussion proceeds slowly until the instructor realizes students haven't done the reading. The instructor then gets cranky at the students for not preparing for the class, and the relationship between students and instructor suffers.

All in all this was a low-workload way of motivating student preparation and attendance, and it seemed to improve student outcomes. By making the penalties for not preparing and attending explicit I respected students' abilities to make their own decisions about their time. Attendance was not compulsory, but it was valued.

By penalizing non-attendance and preparation rather than grading participation and attendance I did not have to grade students' contributions to discussion. This meant the discussion atmosphere was relaxed, because students who attended had prepared, but knew they weren't being evaluated for what they said and did once in class.

The details of the policy would vary in other classes, but the key features I would replicate are

- Preparation and attendance at about half the tutorials was valued

- Other tutorials were less dependent on student preparation/attendance

- Attendance was measured by a reasonable amount of non-graded work that nearly every student was able to regularly exceed

- Penalties for non-preparation and attendance were small at first 'miss', but increasing.

Finally, I must gratefully acknowledge my colleague, Alexander Maxwell, who suggested aspects of this to me, but disagrees with some of my adaptations.

June 24, 2009

The quick and the stupid? Or the clever and the slow?

Do students who finish tests quickly score better or worse? This is an interesting question for educators. For good reason there is an implicit bias towards the idea that if it's done quicker, for the same grade/mark, it's better. Yet there is a time and a place for being quick, and a time and a place for being more considered about your answers.

I had an opportunity to do some "research" on this recently. A colleague and I gave an end-of-semester test to 91 100-level (freshman) students in our American history survey. Students had up to 50 minutes to answer 70 questions, with a range of formats including short answer, multiple choice, and identifications. From our mid-semester test we had a fair idea that the median time to completion would be about 40 minutes. Our goal was a test where the challenge was the content, not rushing to finish.

Because both my colleague and I were heading out-of-town shortly after the test, the students answered the test on a single side of paper each. We collected the paper in a box at the end, and then ran all 91 tests through the scanner. This numbered the pages automatically, and all I had to do after we'd marked the tests was rank the scores on the test in Stata (when you have a hammer, everything looks like a nail).

My prior belief before seeing the data was that there might be a U-shaped relationship between the ranks of completion and handing in. Students who did well would either be quick or slow, tortoises or hares winning the race in different ways. Of course, one could also have the prior belief that an inverse U-shaped relationship would hold for the students who did poorly. Some would complete quickly, either realising they didn't know anything or just rushing through the test to go [insert prejudice about under-motivated students here], while others would do poorly through failing to complete all the questions.

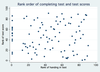

By way of explanation in interpreting the graph, a lower rank on completion means the student waited longer to hand in their test. The vertical line on the left side of the graph is the 12 students who all handed in their tests at the very end when we called "time". A lower rank on the test score is a worse score.

What appears to happen is that there is no discernible relationship between when students handed in their test, and the mark they received. A moving average gives us a slightly different perspective.

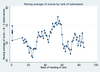

Recall that a lower rank of handing in the test means students waited longer, and note that the overall mean for the test was a score of 51.3 out of 75 (68.4%, a B on our grade scale).

A moving average forward and back 5 observations shows how student performance varied with submission. The 12 students who waited right until the end to submit had a slightly higher average than the grand mean for the class, but nothing that approached statistical significance. There isn't strong evidence that the slower students are more careful and thus scoring higher.

The average rises towards the middle of the order of tests being submitted, and then falls back towards the overall mean. But note what this last fact shows, the students who finish the test earliest are not doing any worse than average. At least in this class on this test, the students who finished early were not rushing to slack off.

In conclusion, there is some relationship between time to complete the test and scores, but it is not an obvious one.

March 2, 2009

Are the people who make courseware trying to create RSI?

Start rant ...

The net effect of "courseware" like Blackboard on teaching productivity is positive. You can distribute notes, links, assignments and announcements to students with minimal effort, and it scales well. Communicating with a class of 15 and a class of 170 is pretty much the same.

But there are some frustrations at the margins.

My biggest frustration with Blackboard is that it does a reasonable job of presenting instructors with the tools they need, but it makes those tools too visible to students. What students need to see is digestible chunks of content and information. That content might be a link to a journal article from the university library, a link to an external website, a discussion board for that week's class, and notes from an associated lecture. In Blackboard the default is to put all these things in slightly different places. The default menu categories are organized by how things were made. It would be like if we distributed hard copy content to students distinguishing between whether they were handwritten, typed on a typewriter, or printed from a computer. It is possible to organize things differently, but it takes a lot more work than it should.

Blackboard is also poor at doing the same thing to multiple items. Today I had to make 15 items from last year's version of a course unavailable to students. In some parts of the internet you would select the items in a list, and then choose the action. In Blackboard you have to go into each item individually, choose your new action (making the item unavailable) and then confirm that's what you really wanted to do, and repeat. What could take x mouse clicks takes 4x mouse clicks, plus all the page loads.

None of this has changed as Blackboard has iterated from Version 6 to Version 8. I always take this to be a small sign of trouble in a software market, when a product gets a new integer version number, but doesn't really get many new features, or change its design substantially.

... end rant

February 20, 2009

My mother always told me not to trust economists

Amongst the many messages I had to read when I returned from holiday was a message with the subject

Dr.George PhD in Economics

This piqued my attention. I like economists, sometimes wondered if I would apply for graduate school in economics before deciding on history. But this was obviously Nigerian spam, where the sender has to establish some credibility before they scam you for money. It was funny to see a PhD in Economics being used as the basis for why you should trust someone enough to send vital details.

My name is Dr.George , Member of Independent Committee of Eminent

Persons (ICEP), Switzerland, and London Office Chapter. ICEP is charged with the

responsibility of finding bank accounts in Switzerland belonging to non-Swiss

indigenes, which have remained dormant since World War II.

January 15, 2009

History on the south side

Last semester I taught a social history course that centred round students doing primary research with the 1924 Houghteling survey of 477 Chicago families. One of the students did a very interesting essay that mapped the distance to work of two groups of employees. Using the file of addresses that he had compiled I then set out to see some of the houses, and whether they still remained. Most of these houses are on the south side of Chicago, where there has been a bit of urban change in the last 80 years.

Setting out with a map and camera I had a list of 40 houses. I did this historical research on foot. To this degree I was being faithful to the original investigators who certainly walked around the Chicago neighborhoods collecting the surveys. With 40 houses to cover I ran. If you are familiar with the south side of Chicago you will appreciate that a white guy running around with a piece of paper and a camera taking photos of people's houses might attract attention. However, I only had one person ask me what I was doing. He was bemused by the explanation that I was an historian. I guess that's what the Chicago Police Department now call undercover agents -- historians. Covering 21 miles (2:50 running, 4:00 total out there) I only got to 31 houses. About half of them were probably the original 1924 house. The results are summarized in the table below for those who are interested.

The diversity of the transformation was interesting. Some of the houses had been replaced by UIC. Others had been replaced by gentrification, particularly in the Bucktown area. Yet others, particularly near UIC and around 18th - 21th St were now largely Hispanic neighborhoods, perhaps today's unskilled immigrant laborers*

This was a particularly fulfilling intersection of running, research and teaching. With the addresses of all 477 families computerized I could envisage a student project to map the transformation of all of these houses. This would even be possible from New Zealand with Google's Street View. But such a project would hearken back to an earlier era of social science which studied neighborhoods as things in themselves. Modern social scientist might perhaps declaim that study of the neighborhood as superseded by a methodological focus on the individual and family in different contexts. So, there goes the neighborhood.

You can see a picture of the transformation here: www.evanroberts.net/chicago_houses

* I hasten to add that I am not implying Hispanics to be unskilled laborers, but am echoing the title of the original research.

| House is now | Total |

| Presumed to be 1924 house | 16 |

| Newer construction, sympathetic style | 2 |

| replaced by industrial buildings | 2 |

| apartment building | 1 |

| Church parking lot | 1 |

| Newer construction, since abandoned | 1 |

| Parking lot for Howard-Orloff Jaguar Volvo car dealer and on-ramp for I-90/94 | 1 |

| Presumed to be 1924 house, but front unit probably knocked down | 1 |

| Presumed to be 1924 house, but front unit probably knocked down? Original survey doesn't mention front units | 1 |

| Public housing units | 1 |

| replaced by commercial buildings | 1 |

| school(?) and park | 1 |

| UIC Environmental Safety Facility | 1 |

| UIC Parking lot for Eye & Ear Infirmary | 1 |

| (blank) | |

| Grand Total | 31 |

July 19, 2008

Library science

After years of research, and some extensive (selective) data analysis on what I can remember, I am prepared to reveal my general laws of library trips.

After years of research, and some extensive (selective) data analysis on what I can remember, I am prepared to reveal my general laws of library trips.

Going to the library will always take more time than expected.

Even after you've adjusted your expectations. Take a reasonable expectation of how long getting a book should take you, and then multiply it by Pi (actual time = estimated time * Pi). Your frustration with the time it is taking you will increase exponentially with your actual time in the library (F = eactual time in library)

There are many reasons for this solid empirical relationship, including the following:

When you need the item urgently it won't be there

The probability of an item being on the shelf decreases with the need for it. If you need a popular item, students from another class will be using it. If you need a rare item, it will be missing because no-one has needed it for a long time and it "got lost when we moved that section of the library."

Popular items will be removed for rebinding when you need them. New copies of popular items are being processed when you need them.

Corollary: The inter-library loan copy of the item will arrive the day after you gave the lecture, or sent off your paper.

Missing book requests have to be filled in by hand at the library

Given the above laws, it is clear you shouldn't actually go to the library, you should just fill in a missing book request without checking the shelves. But ... the librarians are wise to that. If you could just fill in a missing book request from your office, everyone would do it. So they raise the cost by making you go to the library to fill out the request.

It looks suspicious to walk straight in and fill in a missing book request, so spend a couple of minutes out of sight of the desk, and then fill it in.

Series of reports which are not really journals but not really books will be filed inconsistently

The inconsistency will be at two levels. Some of these series will be filed with journals, other series will be with books. But within a series you can expect that the issue you want will have been placed in the other place it could have been.

The public computers on the entrance level will be working, but being used. The public computers on upper and lower levels will be broken, or off because no-one uses them.

Self-explanatory. Also applies (of course) to the photocopiers.

The complexity of other patron's queries will be negatively related to the number of patron's asking questions

As predicted, you can't find that item. It's been moved or lost, so you have to talk to the staff to find it. It's Sunday, so there's not as many people asking questions. But they will have complex questions about accessing unpublished theses from the 1960s that are stored in a locked room accessible by swiping your library card, and their card doesn't work. Therefore, asking library staff anything always takes a long time.

Other people will already be in the middle of the movable shelving when you get there..

It is unfortunate to crush other patrons between the movable shelving ...

The library only started subscribing to the journal you want the year after the issue you want came out.

Or they stopped subscribing the year before the issue you wanted. Who knew, for example, that the Mississippi Valley Historical Review would ever amount to anything? Not Victoria University, who didn't have paper copies of the early volumes. Thanks to JSTOR this isn't a problem for major journals ... but leads to the corollary that the journal you want will be missing for the years you want, and is being digitized next year.

Whatever rules prevail about patron re-shelving will be ignored

I am against patron re-shelving. Except when it means the book I want is filed correctly on the shelf, instead of lying on a table, or on the carts waiting to be reshelved.

January 28, 2008

Amateur digitization for academics, updated

This is mostly an old post, which I've been trying to update, but the updates won't stick on the old post so I'm redoing it as a new post, with a new title. It's probably been the most popular post on this blog, useful to people around the world, and not just historians.

This query about buying a digital camera stimulated me to put finger to keyboard and jot down my collected wisdom about using a digital camera for your research. Some of what I say will pertain mostly to historians—that will be the references to the mysterious archives that conveys a lot to historians and perhaps diddly to others—but the basic idea of substituting digital photography for photocopying will have general applicability for a lot of people.

Getting my caveats up front, I should note that, like photocopying itself, photographing material you could just be reading and taking notes on and being done with, is one of those productive forms of procrastination that feel like work but don't get the real job—writing—done.

That aside, what I outline here really can save time and money over a period of a couple of years. Digital photography is a lot quicker than photocopying (time is money); you can file your documents more compactly, which can be worth a lot if you anticipate/are moving homes or offices; and if you name your files or folders well (and use shortcuts/aliases) you can file your materials more effectively. Some people may ask, what about scanners? Don't bother, is my opinion. Scanners take much longer to record their image, are potentially more damaging to the documents, and are larger and heavier making them far less convenient for traveling to archives. Not to mention, ever tried taking a family photo with a scanner?

The bottom line figures for historians to keep in mind is that if you are photographing quickly and not stopping to examine and select material you can photograph up to 400 pages an hour. A linear foot of archival material is approximately 2000 pages. Thus, allowing for distractions and breaks to prevent RSI etc ... you could photograph a linear foot of archival material in an eight hour day. Do your own calculation here on how long it would take you to work through this reading and taking notes. If you can photograph material I think it quickly becomes an economical option for a lot of research.

The cost-benefit calculation of photographing the documents and returning home, versus going to the archives and reading the material there will depend on your situation. Most importantly, the archive or library has to allow self-copying with a digital camera. This is becoming more common, but may depend on precisely what you are looking at a particular place. As always, contact the archivist before you go! Other variables to consider in deciding whether to hit the archives, photograph and return include;

- What is the cost (time/money) of spending time at the archives? The higher the cost of research trips the more you want to consider the short trip to photograph material. It might be less obvious that the slower you read, the more you should consider the "photograph and run" approach to archival visits.

- Other ways of thinking about archival time versus time with your photographed images are;

- How intensely are you taking notes from something? If you're basically transcribing a page, well, photograping is a lot quicker than sitting in an archive far from home. Taking dictation from dead people, as it were. Though I do grant that typing direct quotations from your sources is an unparalleled way of internalizing the sources you're looking at. In short, if you are doing more than a couple of lines summary of every page you look at, consider photographing it for posterity and note taking later. If you're looking at making some sort of systematic database of whatever (probates, wills, laundry lists, surveys) don't do data entry in the archives if you can avoid it. Photograph it and take it home. This also allows you to double key some of your entries if you have the time and inclination to do so. And once your data is all entered you can verify any strange entries.

- How accurate do your notes have to be? If you write "taht" for "that" there's minimal damage to your research. Indeed, what with modern standards that we shouldn't even sic basic errors like that, maybe none. But if you change a 39 year old to a 93 year old on a census schedule (for example) suddenly someone who was a wife and mother looks like perhaps she should be a great grandmother and mother in law in the same house. That's quite a change. In other words, the more accurate your notes have to be, or the easier it is to make errors while taking notes quickly, the more you want to photograph.

- Do you know in advance what you're looking for? The less you know what it is you're looking for, the more it helps to photograph the documents for later persual, in case your initial note-taking focused on the "wrong" thing. Lists and tables and the like are prime candidates for photographing as they defy easy, accurate and quick summary in notes. If it's in a table it's already a summary so you often can't just take one or two figures from it, as you might summarize a page of an argument in a couple of sentences. If you've ever reproduced a table of figures from an archival source in your notes you'll know what I mean, it takes a while. You have to count the columns and rows, and then decide which way to read the table to enter the data accurately etc. Photograph it and take it home.

- How intensely are you taking notes from something? If you're basically transcribing a page, well, photograping is a lot quicker than sitting in an archive far from home. Taking dictation from dead people, as it were. Though I do grant that typing direct quotations from your sources is an unparalleled way of internalizing the sources you're looking at. In short, if you are doing more than a couple of lines summary of every page you look at, consider photographing it for posterity and note taking later. If you're looking at making some sort of systematic database of whatever (probates, wills, laundry lists, surveys) don't do data entry in the archives if you can avoid it. Photograph it and take it home. This also allows you to double key some of your entries if you have the time and inclination to do so. And once your data is all entered you can verify any strange entries.

- Are you going want to follow up leads you find in material you've copied? How well have you identified beforehand what you are going to copy? The most productive "hit the archives and copy" trips are those where you know precisely what you want to copy before you go, and aren't likely to be needing to use other collections.

- How much do you need to look at? If you only have a small amount of material to work through the traditional approach to visiting the archives should work. The larger the collection, the more you probably want to copy.

- Are you looking at images or small text that is difficult to read? Being able to view an enlargement of your material can be really, really useful in some situations. With a photograph you are not limited to the 200% enlargement you could get on a photocopier.

- Are you going to use it again? The more you are going to re-use a particular page, the more you want to photograph it.

- Do you anticipate giving presentations about your research where you might want to illustrate what you are talking about? Being able to show a slide of the sources you are using can be very interesting for conference presentations, and especially when you have images. As best I can tell from talking to archivists displaying an image in a conference presentation does not constitute reproduction that requires permission since there is no permanent copy of the item being distributed. You should check this for yourself for 'your' collections, but digital photography can open up new possibilities for what you include in teaching and conference presentations.

If you have decided to hit the archives to photograph material, what follows is potted practical advice on how to go about it. It bears repeating, check with the archivist you can do this before you start ...

Camera: To reproduce archival material or modern printed books and journals a camera with a "document" mode is ideal. The Nikon Coolpix range has this feature. Personally, I have been using the Coolpix 5900 which (of course, one year later) has been superseded by the 5600 which you can pick up for $250-300. Apparently Sony also has cameras with this setting. I have been very pleased with the Nikon as it is small and lightweight, while still having a large LCD screen. The 5900 has a 5 megapixel default setting, which is just about ideal for document photography.

Flash and macro settings: The document mode mentioned above defaults to black and white images with no flash. Many archives want you to avoid flash to protect the sources. However, if you're photographing modern material (journals/books) you may choose to use a flash to get better contrast. Beware of glossy pages and make sure that if you are using flash it is not reflecting on the pages. Many older books have non-glossy text and then glossy photographs, so be sure to be aware of this if you are photographing books with the flash on. If you get a camera without a document mode, you want to be sure you can turn the flash off, set it to black and white, and use a close-up or macro setting. This will allow you to focus closely on the pages and get high quality reproductions of the documents.

Memory cards: If you are copying a lot of material you will want high capacity memory cards. On a 5 megapixel document setting, each image is about 950kb, depending on how complicated the image is. Just for comparison, a regular colour photo will be about 2/3 larger again. The image for a nearly blank piece of paper might be as small as 700kb, but if there's lots of text then it might be around 1mb. A 1GB card can hold up to 1300 document images. Your needs will vary, so this is only a guide.

Power source: A lightweight camera (like the Nikon Coolpix range) runs on rechargable lithium batteries which run out relatively quickly. If you are using the battery you'll be lucky to make 400 images before having to change the battery or stop (for several hours) to recharge it. The bottom line is that if you are going to be photographing a lot of pages in a short period of time, then you need at least two batteries so you can be charging one while you are using the other, or buy a power adapter for the camera. A power adapter is relatively cheap, and can be purchased separately from the camera. Unless you are going to urgently photograph a lot of documents in a short period of time (e.g; you are at an archive for one day and can't return easily if you don't finish) start with a couple of batteries, and purchase the power adapter if there's a demonstrated need. Of course, if you have a research grant you need to spend on equipment ...

Copy stand or tripod: Tripods are widely available and with a little fiddling can be set up in such a way that you get good images. However, if you are going to be doing a lot of photography of sources, consider buying a portable copy stand. You can get a good one for approximately $70 (or see here, at buy.com). Note that you will also need a piece of cardboard to lay over the legs of the copy stand to put your documents on so they lie flat under the camera. The huge advantage of a copy stand is that the documents lie flat under the camera. Many tripods can only be configured to photograph the documents at a slight angle, reducing readability and accurate reproduction. If you have a copy stand you can—if you make good copies—do your own reproductions for publication (though be sure to get permission to publish). Many archives charge $10 (at least) for photographic reproductions of material suitable for publication. You don't have to do this many times to exceed the cost of the copy stand. A copy stand is not something any one person will be using all the time, so you might consider seeing if your department could purchase one for loan to people who need one.

How the copy stand works

Since I first published this post, people have asked the most questions about the copy stand. Hopefully these pictures will illustrate it better. As you can see the camera is looking directly down upon the documents, which is difficult to achieve with a tripod, unless you have a tripod arm. The height of the copy stand is adjustable. With the Testrite CS-7 I've been using I can photograph A3 or legal paper by having the camera at the highest point.

Document photography with the copystand proceeds most rapidly with loose leaf paper. The procedure is simple. Put the paper on the stand, photograph, move the next piece of paper on, photograph ... repeat. Doing this it is straightforward to achieve 300-400 pages per hour, though this gets tiring.

Books are slower, since you sometimes have to hold the books open at a particular page. Although this means getting partial images of your hands beside the document text, it is quicker than using beaded book weights to hold each page down.

Source information: Make sure that you include information on the source in the image, so you know where the material came from. If you know ahead of time what collections you will be photographing material from you can print out reference information that you cut into strips to lay beside the documents when you photograph them. These strips of paper should include the collection and library and other information. You can leave space on the paper to add any document-specific information with pencil, erase it, and use the same paper for the next document.

Transferring images and organizing files: If you are concerned with making the most of your time in the archives, wait until the end of the day to transfer images from the camera to your computer. If you have multiple images it can take quite a while, as most cameras transfer data via USB which is not that fast.

Once you have the images on your computer, it really is up to you to organize as you see fit. Since hard disk and other computer failures are more frequent than house fires, whatever you do should include backing up your images at least once. This need not be too complicated or expensive. If you are at a university, you should have access to some form of network server storage provided by the university that is backed up regularly and reliably (onto tapes and stored offsite ideally). This should probably be your first option for a backup. Don't rely on CDs or DVDs for long-term storage unless you want to be spending your time rotating disks and checking that one set hasn't failed etc etc ... Network storage is the way to go as your house is unlikely to burn down at the same time as the university does. If it does you are probably living in an area with geothermal risks or hurricane activity. Or Chicago in 1871.

Software for organizing files As mentioned above I organize my photos into folders and don't worry about renaming them. I sort by the original name within the folder, so that I then browse them in the order they were taken. On Windows I found the best way to browse through photos like this is with Picasa. This is also now the case with the Mac.

It goes almost without saying that if you are going to be doing your research from digital images like this you need a double monitor.

Backing up is the most important thing everyone should do with their images. Beyond that my advice, for what it's worth, is that you find a way of organizing your files that does not take too much time, while still allowing you to find things quickly. You could spend a lot of time renaming all your files from the default digital camera name (DSCNxxxx.jpg, for example) or you could spend it doing something more productive. My approach, and I have more than 15,000 images for my research and this has worked well for me, particularly for documents from archival collections, is to group images into folders with usefully descriptive names. Sometimes a folder relates to just one document, and may only have a few images (pages) in there. Sometimes a folder will initially relate to a whole collection (e.g; all the photographs from a particular magazine over twenty years). When I examine the material in more depth I may create more folders. (Once documents are in folders, renaming them from DSCNxxxx.jpg to "something more meaningful xx.jpg" is relatively straightforward. If you're using OS X, see here. Also pretty quick on Unix. I can't speak as competently to what's possible in Windows)

When I am working with the images, principally what I am doing is reading and taking notes into Word documents. At the moment, for each of my five dissertation chapters I have between five and twenty Word files with my notes on variously defined sub-topics for the chapter. Basically, this is the old historians method of separate thematic note cards, but just done in Word so I can search it. I annotate my notes with both the original source citation and the name of the image file I have of the source. By having the original source citation right there, when I'm writing I can add in the footnote immediately without opening the image file again. But if I want to go back and re-examine the image of the source I can quickly find the name of the file too. This approach works well for loose leaf material from archives.

If you have photographed articles or whole books (old ones, of course, out of copyright) then the folders and original images approach can still be used, but making Acrobat files is even better. This allows you to have just one file for a whole article or book, which you can then organize by adding bookmarks for navigation, and using Acrobat's editing features to add your own comments and annotations. Acrobat can be had for $88 academic pricing. This is only worth the money if you have enough documents you'll be wanting to combine into one file to keep together.

OCR: One extension to this way of working that I am beginning to explore is the possibility of optical character recognition from photographs. If you have photographs of printed or typed sources then this may be something worth exploring to save re-typing information. My guess is that you would need to have a project where you need to re-type quite a lot of data to make this worthwhile. In my case, I have some printed tables that I want in a database. Because of the uniform layout of the material it should be possible to use OCR.

Adding it all up: To undertake your own personal digitization project you are looking at spending about $500-600 upfront.

| Camera | $300 |

| 1GB memory card | $80 |

| Copy stand | $50 |

| Extra battery | $40 |

| Optional to start with | |

| Power adapter | $40 |

| Acrobat | $90 |

| TOTAL | 600 |

I have estimated these costs at somewhat above what you could end up paying so that the comparison with photocopying and spending time at the archives is conservative. Switching to digital photography costs money up front, but the savings in time and money over a period of a couple of years can be substantial. When you consider that most archives charge at least 10 cents per page for photocopying, and often more (50 cents is not uncommon) you are starting to break even between 2000 and 4000 pages copied, even without accounting for your time and travel expenses. Indeed, it's the time savings that can really make digital photography the economical option. If you can turn a two week research trip into a one week research trip, and save six nights at a mid-range hotel and meals on the road there's your $600 and more repaid just like that. One problem is that some funding sources for graduate students and faculty are rigid (backward or asinine, perhaps) in the categories of expenditure they allow. That is to say that travel and accommodation expenses will be paid without questions, but equipment purchases are not permissible. A reasoned statement of how equipment purchases will save money in the long run, and a willingness to make equipment available for colleagues can change minds.

Trivial practical hints: Spending all day photographing documents can be mind-numbingly dull. Bring your headphones and set iTunes to shuffle so that you have something else to think about. Repetitive strain injury is not impossible. Take a break every hour or so, even if you are blitzing through and photographing a box quickly. While CDs are not recommended for long-term storage they can be used for short-term backup while you're away from home. Then if your laptop dies you haven't lost all your work to date, just one day of work.

Other sources of useful information

Columbia: "Going digital in the archives"

Journal for Maritime Research: Historical research in the 'digital era'

George Mason's Electronic Researcher website

American Historical Association: Taking a Byte Out of the Archives: Making Technology Work for You

Notes: Edited on 1 June to add references to multiple file renaming tips.

update, 27 February 2007: This discussion at eh.net on the economic history mailing list is incredibly valuable. Note, in particular, the recommendation to go for ISO and image stabilization over megapixels as criteria for cameras that are good in the archives.

October 11, 2007

Bad apples or bad apple pickers?

Although historians should not be in the business of prediction, I'm going to predict that this column in the Chronicle of Higher Education will generate outrage. A sample:

Working with graduate students is not all it's cracked up to be ....graduate school too often brings out the worst in students -- and, by extension, in faculty members as well....I should have been investing my effort in my own scholarly career rather than helping those who ultimately didn't deserve the help and, more important, didn't respect the life that they themselves claimed they wanted.... What is frustrating is the apparent deceit of would-be scholars enticing you to help them become the field's next superstar, only to discover that it was all bluster and empty talk....What's sad about all of those cases is that the students have lost sight of the real purpose of graduate education: to become a scholar and a teacher whose expertise will make a difference in their field of study, in students' lives, and in the world....It's not that every one of my graduate students has been a disappointment, or that they all exhibited the same boorish behavior that I describe here. I have fond memories of my time with many of them....But the truth is that, for me, the bad apples have spoiled the whole barrel.

Wow, remind me again about that time a columnist in the Chronicle warned people off blogging because people became intemperate on the internet! I don't really expect the Chronicle's columnists to be consistent over time. People have different views after all. My point, however, is that the psuedonymous forum of the Chronicle removes all the important readers from some people's shoulders and unhinges them.

I imagine that mentoring graduate students is not magic or perfect. I also imagine that some of the structural factors the author identifies as turning out bad apples really do exist, and that some people behave badly when they're trying to get ahead. But I do wonder if this author's bad experience with graduate students reflects more on their inability to judge character. As usual, the whole point of a Chronicle first person column is to relate dashed expectations, and the fall from idealism. I can understand the desire to write such a column, working through the fall, but it's not clear to me that the reader gains so much from pseudonymous overstatement and a narrative structure that sets the author out to be initially naive, but now experienced.

September 21, 2007

Genuinelly

Now that I'm on the sample textbooks gravy train I'm not going to get off it by revealing which company sent me this invoice with (count 'em) a misused apostrophe, a missing hyphen, a spelling mistake, and a word missing. But I will say that one of the books I requested was about effective essay writing for history students. So the poorly proofread invoice was especially funny.

Now that I'm on the sample textbooks gravy train I'm not going to get off it by revealing which company sent me this invoice with (count 'em) a misused apostrophe, a missing hyphen, a spelling mistake, and a word missing. But I will say that one of the books I requested was about effective essay writing for history students. So the poorly proofread invoice was especially funny.

July 29, 2007

A good type of wife

This discussion on Crooked Timber about the last known example of academics thanking their wives for typing their books is amusing. If you're amused by that kind of thing ...

June 12, 2007

UMI has a different alphabetical order than normal

All I had to do on Monday morning was print my dissertation, and hand it in both physically and electronically. It's a surprisingly banal ending to several years work. Wars end with dull treaties, and dull dissertations end in even duller Graduate School offices.

You can now submit dissertations to University Microfilms International, who go by their initials rather than their full name, electronically. Amongst other things you have to provide your country of citizenship. Often New Zealand follows the Netherlands. Not in this case, where the order underlying the list eludes me ...

The eagle-eyed among you may also wonder if UMI is anticipating the results of the 2014 New Caledonia referendum on independence. For now, I don't think New Caledonia offers separate citizenship from France.

March 23, 2007

12 point plan

There's more pressure, encouragement and desire for graduate students to publish these days. With that comes a new effort by departments to teach their graduate students how to do so. We were going to have a little panel discussion about this topic at the University of Minnesota History Department a couple of weeks ago, but then it snowed ... and the event got canceled.

This bemused me because I'd been "good," and written up my notes for what I was going to say well in advance. If I'd procrastinated and waited 'til the day before, I wouldn't have a 4 page set of notes (really, I type quickly) hanging round that I won't get any "credit" for. Since one of the things I say in the advice is, "don't write anything you can't use twice," it was a crying shame to write four pages, albeit rough, and not use it even once. Ain't the internet grand for such things? And if I might say so myself I thought what I had to say was marginally helpful, with this nifty 12 point plan for graduate students who wanted to publish.

So, here it is:

- Read about and write a paper on the historiography of your topic in a seminar

- Do some original research as a directed research / Masters paper / early draft of dissertation chapter

- Put it aside for a little while, and then revise based on comments of your advisor and some graduate school colleagues (Form writing groups for reviewing essays)

- Go to a conference.

- Get feedback on paper from people who don't care as much about your topic as your advisors and friends and you have to.

- Evaluate how much work is needed to submit to a journal.

- Revise for a journal.

- Get a revise-and-resubmit from the journal

- Respond to suggestions and criticism

- Send it back in a timely fashion

- Deal with page proofs (much easier these days)

- List on your CV.

If you get a rejection you return to an earlier point in the plan, and try again. That might make it 13 points. The full notes I jotted down are here.

Update, 6 April: Re-reading this, I notice that some of the language is specific to historians, and some again is specific to the University of Minnesota history department. I trust that anyone clever enough to be in graduate school can abstract from the language that is specific to the historical profession to their own field, and think critically about how to adapt it to their own needs. In the pdf version I've annotated what I think are the least clear terms, those that are specific to my own department.

October 20, 2006

Tip o' the day

Microfilm scanners are a wonderful invention, and I'm so enamored with them that in writing this post I browsed the web to see what they cost. At least as much as the top of the line Apple Powerbook and maybe as much as a VW Passat to put it in terms of other desirable items. Of course, the relative prices may change. Not buying any of those things for myself any time soon ...

Anyway, here's my tip for your microfilm scanning. As best I can tell what the scanner does is similar to what an automatic focus camera does—sensing the relative amounts of white and black in the viewfinder and then capturing the image. Now if you've ever taken photos on an automatic camera you'll know they are easy to fool by composing a shot that is a mix of both dark and light areas. Same goes, it seems, for the microfilm scanners.

If you have significant amounts of the black film between the pages in your images, the digital image will not be as well exposed for the part of the image you want. Previously my preference when using the microfilm scanner was to have the black space on the side of the page, rather than cropped parts of another page. This works OK for pages that are quite dark anyway (whole pages of text). It works poorly when you are trying to capture an image of a page that has a lot of white space in it—tabular data, for example—because then the automatic exposure settings can't cope very well, and will wash out the detail you are interested in.

Bottom line advice is this: For the best exposure on microfilm scanners try capturing an image without any of the black film space between pages.

May 28, 2006

Attaching spousal characteristics for IPUMS datasets in Stata

First draft of a program for attaching spousal characteristics in IPUMS datasets using Stata

capture program drop spousal_char

program spousal_char, sortpreserve

capture drop _merge

tempfile spouses

sort year serial pernum

preserve

keep year serial sploc `0'

rename sploc pernum

foreach i of local 0 {

capture drop sp_`i'

rename `i' sp_`i'

label var sp_`i' "Spouse's `i'"

}

sort year serial pernum

drop if pernum==0

save "`spouses'", replace

restore

merge year serial pernum using "`spouses'"

end

Once you have run the program you can attach spousal characteristics by typing

spousal_char [varlist]

Obviously some improvements could be made ... at a later date.

May 27, 2006

Useful Stata finds of the day

translate for translating .smcl logs to text and vice versa.

Stata syntax highlighting for Text Wrangler.

AlphaTcl with even better syntax highlighting.

April 8, 2006

Non-anonymous peer review

Interesting article in the Chronicle of Higher Education about how Microsoft Word's feature of saving the name of the people who edited a document can accidentally corrupt anonymous peer review. An astonishing number of people who should know about this (journal editors) admit to ignorance on the matter.

December 8, 2005

Industrial Arts Index

Good day in the archives. I came across a fat, fat publication called the Industrial Arts Index that indexed books and magazines in what we would now call business and technology. But in 1913 they called that kind of thing "industrial arts." Anyone doing any kind of research on early twentieth century American business or technological history should be acquainted with this publication. A quick World Cat search shows that it's widely held by libraries around the country, but not everywhere has complete runs (UMN Twin Cities does.)

Copying the index pages on "Woman -- employment" saved me from looking through multiple volumes of old journals like Factory and Industrial Management to find the articles about women in the workplace. They did not restrict their indexing efforts to manufacturing and extractive industries, also covering what they would have called "commerce" in the 1920s.

It is, of course, an old school index. You have to physically thumb through and look for your keywords. But there is extensive cross-referencing. Thus, under "Woman --" they pointed you to related terms such as "Business woman" or "Farm woman."

November 14, 2005

DDF seminar presentation

On Thursday I gave a 15 minute overview of my dissertation to other dissertation fellows in the Doctoral Dissertation Fellowship seminar series. The other presenters were very interesting -- it's cool to see what ones peers (in the broadest sense) are doing.

Here is a copy of my slides in PDF format, on the suggestion of one reader who was not able to make the seminar.

November 11, 2005

Feast on rss feeds

Maybe this ain't news to many, but most journal publishers now offer RSS feeds of current contents (Cambridge & Chicago university presses; Ingenta has thousands of journals for example). Somehow I slightly prefer this to the email updates that presses have been offering for a while. I note that Project Muse, which has a bunch of good titles, doesn't have an RSS feed (but does email updates), the History Co-operative has neither.

It's kind of time consuming going through all the various sites, and thinking "might I possibly be interested in articles in this journal?," clicking subscribe, filing it in the bloglines folder ... but time consuming meant a couple of hours on a slow night, RSS will be around for a while, and this will save random web-surfing to see what's in the journals. Not to mention actual physical trips to the library to see what is in the journals. That really is time consuming!

October 19, 2005

Baumol's disease and the historian in the archives

Matthew Yglesias and Fontana Labs discuss how the price of higher education just keeps going up, and wonder when the thin reed that is middle class parent's finances will break, and they'll all send their kids to the University of Phoenix.

In general this phenomena is known as "Baumol's disease," (James Surowiecki has a good introduction here), and it's particularly relevant that the industries afflicted—health care and education—have a large extent of government funding, even in the United States.

I tend to think that part of the problem is that "productivity" in these fields is difficult to measure. If you measure productivity in education by the number of children in a classroom, well, yes, that's not going to rise if you want to keep class sizes small. But to stick with education for the moment, if your measurement of productivity is "knowledge acquired," well there have been an awful lot of improvements in productivity in education and health care in the past century. Calculus, for example, was once a subject reserved for Masters students taught individually or small (2-3) groups of students, now it's introduced at the junior year of high school. Similarly, in health care, if you measure patients treated per hour by a doctor, well sure, there has been little improvement over the years. But the productivity of a doctor's time has increased markedly over the century, thanks to improved drugs etc.

I might be reading Baumol wrong, but the problem with his analysis seems to be that he focuses on productivity measured in units of output: patients seen, children taught in a classroom, for example. But is this the appropriate measure of productivity in health or education? I think not.

Health outcomes are difficult to measure, but there are better measures of productivity in health care than patients seen, such as years of healthy life added, mortality or morbidity avoided etc. In education, the pupils are themselves an input to what is being produced, so it's not clear to me that it's appropriate to count them as an output too.

I was thinking of these issues just last week at the National Archives, where I was photographing 9000 pages of surveys from the 1920s. It's great that the National Archives allow you to do your own copying, and don't charge for you it, because if I had to photocopy all those pages it would have cost about $1500 and I would have boxes and boxes of paper that is easy to lose. The digital camera could make some fundamental changes to the way historians approach archival visits, allowing us to "hit" the archives, copy what we need quickly, and then go analyze it at home. Clearly this wouldn't work for all historical research, including parts of my own, but a lot of trips could be shortened this way.

The laptop too, by speeding up note-taking and making it more legible, has also improved historians' productivity in the archives. But really the method of history is little changed since Ranke. For the most part we sit there and we read.

As any historian whose work covers the turn of the twentieth century will tell you, the productivity of reading for research increases markedly when the costs of printing and typewriters came down. It really is incredible how much more quickly you can do research with printed compared to hand-written sources. But whether this compensates for the increase in the volume of material that can be read is debatable. In short, the productivity of historians will always be limited by the speed with which they can read, and then the speed with which they can think and write.

In research as in teaching, Baumol's disease is apparent. Yet productivity is not just measured in units of physical output. It is also measured in the value of the thing produced. At least in the case of health care and teaching the marginal value of labor may well be increasing, as better health and more knowledge are produced in the same amount of time. Moreover, if people are prepared to pay for the output of these services, and pay increasing amounts over time, then the marginal value product of labor in services can also increase.

By this point, if not way, way earlier I've probably lost most of my audience [Earlier. Much, much earlier. -ed.] But my point is this -- the productivity of labor intensive service occupations like teaching, research, and health care has increased through the application of technology and should continue to do so over time. Even the humble blog has contributed to this; as I've mentioned before, in the not so distant past if I'd wanted to share my thoughts with the world I would have had to print this out, and then send it to people I thought I might be interested. Now I can publish it for all to see, whether that is 1 or 100 people.

September 23, 2005

Conference papers

The formal session is dead. Long live the formal session!

Timothy Burke is all for eliminating the "formal session" from the American Historical Association conference. He says:

The formal session is a kind of loathsome ritual of humanities and social science academia, a lacerating gesture of masochism. Three, sometimes four, panelists read dully through a pre-written paper. Every once in a great while, one of them has actually written a shorter version of the paper designed to be read aloud, that has some vague hint of a performative gloss to it. Mostly though presenters just put red lines through paragraphs they want to skip, rush through the end, make amendations on the fly, read prose intended for formal publication.

... and goes on to say this ...

I suppose someone could say that's not how it should be, that formal sessions could be run better, but why reform it? The formal session is an inevitable bore. The only time conference meetings on papers work is when papers are precirculated (and read by the audience), and there will be some of these at the next AHA meeting. (emphasis added)

Burke's thoughts must be shared, as the email I got about my Organization of American Historians session next April said

The OAH has made a commitment to provide a more dynamic, innovative, and interactive annual meeting. We strongly encourage participants to present or "talk" their papers from notes, speaking directly to the audience, rather than reading their work line-by-line ... To allow for more audience participation during paper sessions and the more colloquial presentation mentioned above, the OAH provides the option of posting papers on our gated website prior to the meeting. Posting your paper will allow attendees to read it before the Annual Meeting and be prepared with questions and comments.

Yet I know the frustration of which Burke speaks. I once attended a session at Social Science History Association—where most of the papers and presentations are quite good, in the British sense of quite—that represented the nadir of the "formal session." While the papers were on closely related topics, one presenter had pulled out. It was the first session of the conference, which traditionally at SSHA means low numbers, due to people not arriving until later on Thursday. The first speaker, a graduate student (on the job market, I could tell before he even alluded to this, because he was wearing a suit. At SSHA, yes, at SSHA, a very informal conference) read his paper in a monotone. As the only audience member for some time I felt that I could not leave, but I knew the speaker would not notice for he not once raised his eyes from his task of reading his paper verbatim. I had high expectations for the next speaker, a full professor at a Big Ten university whose books were models of lucid prose. But no, it was worse. She also read her paper. The nadir came when she described a cartoon. She did not interest her audience (now doubled) with an overhead or handout of this cartoon, she took several minutes to describe it.

Despite this experience I am here to praise the formal session, not to bury it. It's not hard to learn how to distil 30 pages into 7 (7 pages is about 15 minutes talking), and present it to an audience. It's not hard, even for historians, to learn how to operate an overhead projector, and display some pictures to their audience. Not hard at all, it really just takes a little practice.

Perhaps it is different at the large mega-conferences, I have tended to go to more specialist ones where the papers are often on cognate topics, and someone in the audience often knows some background, and can ask good questions.

It is, I think, a good discipline for presenters to have to assume that their audience has not read the paper, and may not know much about their topic. I worry that if people were just allowed to pre-circulate papers and discuss them, that people would begin treating major conferences like in-house workshops and seminars. The value of the formal session for the presenter should be that it provides some incentives to distil their research into a concise presentation for intelligent people who may be ignorant of the precise topic.

When you pre-circulate papers the readership rate is typically between 0 and 1. It's very rarely 1, and more often 0, I'd wager.

If everyone read the papers circulated, then this model would work fine. Questions would mostly be devoted to what is in the paper, and some discussion would ensue. And if the presenter knows that the readership rate is going to be 0, then they have every incentive to make a good presentation, and get some feedback from that.

But when it's between 0 and 1—some read the paper, some don't—not so great. Without being able to deny entry to people who haven't read the paper, what does the speaker do? Well, typically they discuss the paper assuming that people have read it, and rightly so, from the presenter's point of view. But then you get the inevitable questions from people who haven't read the paper, asking for clarification and explanation. "It's in the paper," is one response, and perhaps you could say "No questions without having read the paper," but you be the chair or discussant that tries to enforce that ... I'm not sure that would work so well.

My point is that the formal session is a good idea gone a little wrong. It's a good idea because it should help the presenters/authors think about what's truly important and interesting in their work. The solution is not to abolish the formal session, but for historians to improve their presentations. The costs of this training are remarkably low, it could very, very easily be incorporated into the structure of existing graduate seminars or courses.

If you think this difficult to achieve, I would just invite you to attend conferences outside North America. The dull, monotone reading of the paper is a North American problem -- it's much less of a problem in Europe and Australasia where the standard seems to be a snappier 15 minute presentation, not quite ad-libbing it, but speaking from notes.

September 22, 2005

Articles from my past

Publications are a little like purchases on the credit card—payment and pleasure are quite separate.

My article on economic evaluations of community mental health care—jointly with two fine colleagues, Jackie Cumming and Kathy Nelson—came out in Medical Care Research & Review today. As best as I can understand the terms of the copyright do not allow me to post a copy on my own website, but do allow me to say that I can email you a copy if you're interested. In such a manner they protect their subscription revenues. 41 pages. Not to put you off. Some may find a cure for insomnia in what I offer.

Not to sound old or wise before my time, but a little reflection here on the value of persistence for academics. You might not have the time now to get that paper done, but never let the motivation to get it published die entirely. Just because it is a couple of years since you worked on something, doesn't mean you can't pick it up and take it somewhere. I think this particularly applies to people who have nearly-publishable things while nearing dissertation completion (this is a reminder probably more to myself than it is to any actual readers I have). The dissertation needs the most attention, but tell yourself that you will publish the other stuff later. Unless someone is likely to scoop you, or there's a debate that cries out for your input, you can probably put the non-dissertation manuscript in the filing cabinet until next year.

I started work on this paper in November 1997, it went through several iterations in-house, we first shipped it out for review in April 2000, sent it to MCRR in early 2001, and then shepherded it through a revise and resubmit, updating the paper to reflect changes in the literature since initial submission, and final acceptance.

Working with co-authors has real benefits, but at various times the paper fell off everyone's metaphorical desk, with the more pressing tasks of dissertations and exams and reports due to people who actually pay good money for my co-authors' advice on health care.

I thought that once the paper was done I might be able to have a ritual dumping of some of the files associated with it (literature reviews generate lots of photocopied articles lying round your desk) but I flatter myself with the thought that a reader may write me with clarification on some trivial point. So perhaps I should keep them for a while ...

September 19, 2005

Survey

Rebecca Goetz is conducting a survey of graduate students in the humanities and social sciences who blog.

She asks

- Your blogís title and URL

- Whether or not you are on the job market

- If you include your blog on your CV or other job applications material

- If youíve interviewed before, were you asked questions about your blog? Did blogging come up at any other time in the process?

- Briefly or not so briefly, why do you blog?

Follow the link to respond.

August 31, 2005

Endnote 8 or 9

Right on schedule, with the academic year just starting, Endnote has announced their annual integer upgrade that promises only minor new features (as I noted last year).

In a sign of how seriously the company takes its own product, they obviously recycled last year's press release, and forgot to change the HTML in the title.

(Image taken by the incredibly useful and free Snippy, recommended at Lifehacker)

July 14, 2005

Page proofs

Page proofs for my forthcoming article in Medical Care Research & Review have arrived. The joy of forthcoming publications is always tempered by the concentration of checking the proofs, and trusting that crucial words or numbers have not been mistakenly excised somewhere along the line.

So, you can guess what I'm doing first thing tomorrow. Not blogging ...

June 8, 2005

Grades and summer deadlines

Right now I'm feeling a little of the "Summer Vertigo" that Kieran Healy describes so well, and that afflicts others too. Gallows cameraderie!

In category 1 (Stuff you should be finished with already) I have a manuscript that got a reasonably positive revise-and-resubmit a couple of years ago that I couldn't revise in time for their deadline. I thought then "when I'm ABD I'll have time to revise this." Even then I knew that was optimistic, but it seems even more foolish now. And then there's personal stuff like doing my photo albums from my three-month excursion through Australia, Vietnam and America from five years ago ...

Category 2 (Stuff thatís been on the back-burner for a while, but is doable now you have some time) is spending sustained time on the dissertation rather than little bits of time in between other activities.

Category 3 (Fantasy projects) is remarkably empty. The weight of doing the other stuff has beaten the imagination out of me!

Right now I'm deluding myself into thinking that the month after the marathon will be unusually productive because I'll just be jogging around for 30-60 minutes a day, rather than spending 90-120 minutes out there each day ... We'll see how that works!

March 11, 2005

Once more and it's a trend

In just the past fortnight I've read two complaints about the whining dressed us as an essay that makes up the Chronicle of Higher Education's First Person section.