June 2, 2011

Thoughts on the Twin Cities marathon course

It gets harder after 20 miles. But all marathons get harder after 20 miles, or you're not doing it right. On the internet and in real life, opinions on the difficulty of the Twin Cities marathon course devolve into what seem like two opposing views

- "it's a tough course with the long climb after 20 miles" or

- "don't be so soft, it's not a big hill at all."

Since in my day job (which I should be doing right now) I'm paid to be a professional "difference splitter" I confess I don't actually see these views as total opposites. It's not a big hill, it's 150 feet (50 metres) in 3 miles (5km), and then you undulate down to the finish. But the toughest climbs on the course do come from 20-23 miles. You can't throw everything into the effort to get up the hill, because there's another 3 miles to go once you've made the climb. But you should be working harder, it should be hurting more, the further you go up the hill. The question is, how much do you give up climbing the hill relative to your pace on the flat? Conserving energy for the next 5km versus losing time?

At 20 miles you're looking for any advantage you can get, and climbing a hill is not an advantage. If you're having a good day the climb won't slow you down much, but if you're having a bad day, the hill will probably magnify your problems.

Taking advantage of living just off the course my not-secret-at-all training plan is to get in a few of my 10+ mile marathon-pace runs on the course. The goal is to simulate a bit what it will feel like to go at marathon effort up the hill. I did the first of these today, doing 7 miles before I got to "mile 20", and finishing at Summit and Snelling. After averaging 6:22/mile on the flat section I was pleasantly surprised to average 6:40/mile the next 3 miles. This conformed with my expectations that the hill is worth about a minute at my pace.

I'm hoping marathon day will be easier than today, since today I faced a 20mph headwind up Summit, and was running on the sidewalk for quite a lot of the way. After nearly 15 miles of running in racing flats I could feel the difference between concrete and asphalt...

September 1, 2010

I encourage "that clicking sound"

In a really good discussion of how technology has altered historical research David Turner writes

My only complaint, and I don't know if this is a complaint to be aimed at the camera manufacturers or the historians, is that I wish that there wasn't such a loud clicking sound when cameras take photos.

He's right that most digital camera users at the archives could eliminate that clicking sound. Digital compact cameras have the clicking sound merely to replicate the aural experience of a "real camera". Digital SLRs (and film SLRs, though how many people do archival photography with film?!) have to make that clicking sound. It's the sound of the shutter opening and closing to expose the sensor (or film) to light.

My most popular post on this blog has been Amateur Digitization for Historians, and I would now add one further variable to that discussion about digital compacts versus SLRs in the archives.

By way of background most archives don't allow flash (protecting the documents and protecting you from flash glare on glossy paper obscuring your images), and some archives don't allow copy stands, tripods and other stabilizing equipment. So a big concern in the archives is taking sharp photographs in low light holding your camera by hand.

Digital compacts typically use very high f-stop values which means your typical photo from a digital compact is sharper across the whole image with a wide depth of field. The foreground, center and background are all close to being in focus. But a high f-stop is not great in lower light (even room light), so many digital compact photos from archives without flash come out slightly blurry.

By contrast a digital SLR allows much lower f-stops than compacts. Now, with a lower f-stop your depth of field is reduced, but this doesn't matter as much in typical archival situations. Most parts of the paper are the same distance from the lens. SLRs also allow the user to set a very high ISO. This means you can compensate for the lack of light. Whereas a high ISO on film used to give you a very grainy image, digital SLRs give a much greater range of usable ISO values.

So, the short version of my advice is that if you can't use a stabilizing device, consider using an SLR for archival photography. You will lose many fewer photographs to being blurry than with a digital compact.

Another non-trivial advantage of the digital SLR is that it is much quicker. On a digital compact I find I can take about 400 photos an hour in the archives (mindlessly flipping from page to page). With a digital SLR I have taken over 1000 photos in an hour.

I think Turner's right that laptops, digital photography, and digitization of text are making fundamental changes to the practice of being an historian. My senior thesis advisor told me in the mid-1990s that how we do history hadn't changed much since Ranke or Beatrice and Sidney Webb (who wrote a great book about social and historical research). People looked at documents with their own eyes, and took notes. Then they analyzed and wrote about what they'd seen. Distance was a barrier to archival research. To be sure, the writing became quicker with the introduction of word processors in the 1980s, and computerized archival and library catalogs meant searching for sources was easier. But the process of primary historical research with old documents has been transformed in the last decade. Distance is less of a barrier to historical research, and the productivity of historians will increase tremendously as we take fuller advantage of the new technologies.

August 30, 2010

Measuring up to metric and imperial systems.

No really, metric is interesting. Returning to America has reminded me of the absurdities of imperial measures in everyday life, but also that metric enthusiasts overstate the benefits of metric. Although Thomas Jefferson proposed a decimal system for America in the 1790s, I don't doubt that if further metrication was proposed now it would be condemned as a foreign invention, and contrary to American tradition.

When I first moved to America I was irritated by silly imperial measurements, but more outraged by silly international students who, though intelligent enough to be studying abroad, could not comprehend alternative measurement systems. Being a sometime contrarian I found more virtues in the imperial measures than I first suspected.

Not the least of these virtues is that there are fewer miles in a marathon than there are kilometres. Of course at the same speed the miles take longer to pass. But mentally I find a marathon would be best measured in miles to 20 miles/10km to go, and then in kilometres. After 20mi/32km time is appearing to pass so slowly in most marathons that the achievement of an extra 0.6mi/1km is good to know about.

Other virtues can be found in the temperature scales. When you get below freezing it's nice to still be referring to positive numbers. This saves words, you don't have to say "negative eight," you say twenty. It also allows you to push back the point of being expletively-cold to below zero in fahrenheit, which is about right.

The point is that when you're only thinking about one measure it doesn't matter whether that is metric or imperial. So long as you know the practical implications of the distance or the temperature it doesn't actually matter what scale it is measured on.

Instead, the absurdities of the imperial system are when you have to convert between scales, and when you are relating two measures to each other. Lets take the first of these issues. Ounces and pounds are common measures of weight, and there are 16 ounces in a pound. OK so far, though base 16 is not the most intuitive (base 12 makes more sense than many realize). The problem comes in the store, where some items are weighed in decimal amounts of pounds rather than whole ounces. The conversion isn't obvious between scales when you have some cheese measured at 0.593 pounds and you recipe called for 10 ounces.

It's worse for volume and liquid, there are multiple measures -- fluid ounces, cups, pints, quarts and gallons. Quite why it is sensible to have 10 fluid ounces in a cup, 20 in a pint, and then (then!) switch to 2 pints in a quart and 4 quarts in a gallon. It's not intuitive at all.

The chances of changing this mess are small, since changing United States institutions is difficult at the best of times. Of course the costs of not-ideal measurement systems are small every time you use them, but add up over time and across society. They are probably worth the transition costs, but it will never happen.

August 3, 2010

Excuse me!

One thing I didn't anticipate about moving back to America 10 days ago was that things I got used to in the 7 years I previously lived here could appear like new cultural experiences and misunderstandings.

To wit, I had completely forgotten how Minnesotans drive me insane by saying "excuse me". PLEASE STOP IT.

In New Zealand you do hear people say "excuse me" as a genuine polite acknowledgment of minor social faux pas (burping, reaching too far for the condiments at dinner, stepping into someone's way by accident). But when I heard "excuse me" in New Zealand it was reasonably frequently used by the wronged person—the person who only had to hear the burp, the person who saw another's arm come across their plate on the way to the mustard—as a sarcastic way of indicating that the uncouth person should have acknowledged their bad ways. I think (and I'm no linguist) that people in New Zealand say "sorry" more frequently as an expression of genuine contrition for these kinds of offences.

Soon after arriving back in Minnesota I was in the store, and waiting to turn the trolley/cart out of an aisle. Someone passed in front of me with the right of way (applying road T-junction rules to the supermarket) and said "Excuse me." This was ridiculous because they had the right of way, and I had stopped briefly waiting for them to pass. To say "excuse me" raised my hackles. I felt the rush of annoyance one feels when strangers are rude to you in public without cause. Why, I wondered, are they being so rude and suggesting that I should have apologized when they had the right of way and I was waiting. There have been several other sarcastic Minnesotans since then, saying "excuse me" and obviously prompting me to apologize for my behavior.

Reflecting on each situation, I think they were just trying to be polite. Indeed one of the reasons I think they are being sarcastic in saying "excuse me" is that, to my mind, there's nothing for them to apologize for in the first place! Thus my next instinct is they must be suggesting I did something wrong. So, it would be a lot easier for me if people in Minnesota could just stop saying "excuse me."

May 13, 2010

But now they can create a variable for overly_sensitive and dont_understand

This story is a doozy for academics (chronicle of higher ed version, sub required). Two business school professors sent a fake email to 6300 professors purporting to be from a prospective PhD student, with different versions of the email asking for an appointment now (today) or later (a week away). Different versions of the email also varied the apparent race and gender of the student.

Deception in the name of research. It's been done before and will be done again. A really important question is whether the impact on the deceived is outweighed by the scientific benefit of obtaining possibly better estimates of what people think and do. It's all very well for an historian to say "Involving colleagues, or any human beings, in a study without their knowledge and their prior consent is unethical," because historians rarely face this issue. Historians who use social science research so often delegate the dirty business of data collection to people long before us.

I happen to think that this kind of field experiment (it's not really survey research as some people think) is necessary. In the first instance there's the research done by sociologists and economists about racial and gender discrimination in housing and labor markets. You can't do this without deception, and there is to me a clear greater good in knowing the extent of discrimination in society.

But a more abstract and important question is how does measurement affect behavior? People say different things in surveys than they subconsciously reveal in laboratory experiments. But even in laboratory experiments people know they are being studied, and it's quite likely there's some kind of impact on their behavior in that setting. So field experiments where people don't know they're being studied, and might be [nearly] harmlessly manipulated are necessary to work out how people respond in different situations. Research involving deception has inherent risks, but that's a reason to monitor it closely and make sure the consequences for the deceived participants are low, not to never do it.

May 11, 2010

Why not just fund schools a different way?

The poor will always be with us. What a lot of social policy strives to achieve is that the poor are more of a random, changing aggregate and not a static, related and identifiable group. Unfortunately there is lots of evidence that poverty is persistent. Here is some American discussion of that issue showing how race, housing, education all contribute to poverty. One of the peculiar American aspects of this discussion is the implicit identification of "urban" with "poor" and "troubled." In a lot of American academic and policy discussion this language flows quite naturally, as if it were just natural that inner cities (urban) were poorer than suburbs.

Some of the policy discussion that follows is then all about moving the people. Thus in the 1970s school children began being bussed long distances to school to pursue racial integration. And still today. However the explicit goal of racially integrated schools is less common, giving way to the goal of giving children in areas with poor schools the opportunity to go to better schools. Laudable goal, and perhaps the least worst method possible in the circumstances. The other way to move people is to move their residences, so American research on race and poverty often comes to focus on how to reduce housing segregation.

The goals here are worthy, but one thing I don't quite understand is why there isn't more effort to substitute state for local funding of schools. Money is fungible and moves across city borders somewhat more easily than people. The local control of schools is long standing in American education, but that doesn't make it right for the future.

It's the kiss of death to any suggestion for American reform to say that "other countries" do something, but it really is true that in other comparable countries with problems of race and poverty, some of it is mitigated by the education system that directs resources from richer to poorer areas through state/province or national taxes.

April 15, 2010

Paying twice as much to get twice as much

I'm sure the usual idiots will be out loose on the internet soon explaining why the fact that the United States spends twice as much of its national income on health care as the average OECD country, and has a maternal mortality rate of twice the OECD average is just awesome, and actually shows the superiority of the US healthcare system (and the wisdom of the Founders etc etc), but in the real world you have to wonder ... Is paying twice as much to not even achieve good basic healthcare results worth it? Healthcare is a big ship to turn around.

(Sane and informed commentary)

April 11, 2010

Why Whanau Ora should be evaluated

If the key idea behind Whanau Ora—that social service agencies should work more closely together—was so good, it would have worked the first time. And therein lies the problem. The idea that social service agencies should work more closely together is not an innovation in social services, but a recurring staple of reform.

Of course every generation of policy makers and social service workers has to discover this for themselves, and dress up the resulting discovery in a local context. Hence the name Whanau Ora. Every decade in the twentieth century some government or social service agency in the western world was "discovering" that health, education, criminal justice, and housing problems and solutions were intertwined, and that a solution was for institutions and professionals to talk to each other, and work a little better together. Things were maybe more integrated in the nineteenth century when "charity visitors" were untrained, well-meaning middle class men and women visiting the homes of the poor to see what they could do to help. Someone could usefully write an article pointing out the long recurring history of this new idea, and make it compulsory reading for social policy analysts.

Social services became less integrated with professional training and specialization in the late nineteenth and first half of the twentieth century. The 1920s and 1930s saw lots of calls for integrated services as the first large generation of social work professionals examined their field. It was this impulse that gave New Zealand milk in schools and health camps for sick children. Same idea, different time period. And certainly not unique to New Zealand.

While you can't really question the sincerity of the ideals and ideas behind the policy the fact that we've had this laudable impulse to integrate social service before and it didn't solve all our social problems then means we need to be skeptical of the idea that Whanau Ora will work that much better than the services already in place. That's not to say that Whanua Ora will fail, just that people who are not trying to sell you a political policy should assume any government initiative is no better than what it's replacing until proven otherwise.

Whanau Ora will very likely look great in the first year or so. Positive stories of families helped and crises averted and multi-cultural harmony unfolding will be easy to uncover. Were one to do an evaluation of the old and the shiny new services, the shiny new services would look good. Social service workers, like everyone else, often throw themselves into the new thing enthusiastically. The real question is how do things compare in year 3, when this is no longer the exciting new programme that the government is supporting? I am pretty sure we'll never find out the answer to that question. There is also a near certainty that something bad will happen in at least one family receiving Whanau Ora support, and this will look bad for Whanau Ora in the Sunday newpapers. That's unfortunate too, because no social services eliminate all the nasty things that happen in families. The important question is what minimizes nasty stuff at an acceptable cost.

Calling for integrated services and a holistic focus on families is easy. Getting it to work in practice and show that it's worth the upheaval in what we currently do is more difficult. The flipside of enthusiasm for new projects and new ways of doing things is that some people doing a totally OK job of working with families in need don't like having their routines disrupted. There are lots of possible models of integrating services. The idea has recurred so often in the past hundred years that the evidence for integration is, of course, mixed. Sometimes it works OK, sometimes not so much. The specifics of the policy and practice matter. This iteration of an old idea will be different again in how it works. So it's entirely possible that moving to new service models is bad in the short-term. The point is, we don't know. We won't know unless we try and find out.

What we do know is that how the families respond is critical. One thing that's hard to do in social services is blind evaluations. People know if they are getting the new service. It's not like drugs or surgery where you can trick people into thinking they're getting treated. Since the response of families to social interventions makes a huge difference to the effectiveness of those interventions, perhaps some good will come of this. In that sense pretending to do something new in social services every few years is not a waste of time or a forgetting of knowledge, but a necessary part of making the people being served feel someone cares. But you still should find out that the reorganization didn't make things worse, or cost a whole lot more.

Good ideas and the thrill of the new are not the same as good outcomes. If the good idea of integrated social service delivery was that good we wouldn't have a century long international record of people calling it a new idea. It is a good idea, but it's an old idea whose time has come, and will come again, and again. Print this out and come back to me in twenty years, and we'll probably be onto the next integrated social service initiative.

If the New Zealand government is really committed to redesigning the way it delivers it billions of dollars worth of social services it should implement Whanau Ora in a limited way and see that it works. But that is not often the New Zealand way. There is an assumption that new programmes just work, and that it is inequitable to deny people the benefits of the unproven new thing. It makes for good politics in the short term because it looks like the government is doing something innovative to improve people's lives. But it makes for bad policy in the long-term because we don't know what really worked.

April 8, 2010

There was no golden age of original content

Interesting discussion at Crooked Timber about how much original reporting there is on the internet. Not much. Or maybe a lot. All depends what your prior expectations are, I suppose. There is certainly a lot of recycling of content, and probably there always was.

Now that we are lucky enough as historians to have access to lots of digitized text we can see the scale of this problem historical question more easily. A decade ago or more when I first got my hands dirty in original research, I used to think there might have been some golden age in the nineteenth century where newspapers and magazines had a high proportion of original content.

Why the nineteenth century? I suspect that publications with lots of original content are going to come in highly literate societies with printing presses, but despite that relatively limited communication to the outside world. Now, this does describe some significant parts of the world in the nineteenth century, Australia and New Zealand, parts of the American Midwest and West, and South America; the "regions of recent settlement" to quote an imprecise but known scholarly phrase.

But once you get cheaper transport, and then the telegraph, I suspect that the books and magazines of these regions are going to start reprinting material from elsewhere. And why not? The locals (recent in-migrants) wanted to know what was happening elsewhere, where they'd come from, where their friends and relatives had gone, and where they might move too. Indeed you have whole sections in nineteenth century newspapers labeled "News on the latest ship" or "News from the wires" (or something like that).

Not only that but the nineteenth century is full of books that are nothing but reprints of extracts from newspapers and magazines.

The other thing the digitization of magazines and newspapers has shown me is that it wasn't only news that was reprinted and not original (tho' it might have appeared original), it was, of course, also opinion pieces. The obvious successor to the political pamphlet was the newspaper column. Small town and city newspapers were particularly rife with this kind of reprinted stuff.

In short, reporters have long been rewriting someone else's copy and passing it off as new. I'd start with the hypothesis that this is an historical constant and not a decline in modern standards.

Flying business class: like a youth hostel in the sky

The latest episode in Duncan Garner's exposing of Chris Carter's travel shows two like-minded men really made for each other. Both men have opted to appear to be doing their job, rather than really doing it.

For a little-bit-lazy political journalist, what an easy story. Politician flies business class to Europe! Something few experience, but many can understand, having glanced at the forward cabin as they board the plane. And the sums involved are comprehensible, thousands rather than millions of dollars. But lets not romanticise business class travel. Sure, it's nicer and more expensive than economy, but you can have a lot more indulgence on the ground. If long haul economy flying is like sleeping in a tent on a hill and being served reheated food, business class is like sleeping in a youth hostel and being served slightly better reheated food. It's nicer, but it's not that nice.

But most people don't travel business class so it's easy to foment indignation at a politician getting a slightly better deal than others. Even in business class you can't avoid the fact that changing time zones rapidly screws your body clock. Nothing you can do but wait to adjust. The only thing that business class gives you nowadays is the option to sleep flat on your back. Especially if you're a tall guy, like Chris Carter. And if you really have to perform straight off the plane, then business class is probably worth it. It's just a little hard to believe that an opposition spokesperson going on a 3 week trip to Europe has to perform straight off the plane. Fly economy, and add an extra day to the trip, and it would all be OK. Probably no nasty TV3 coverage.

So it's easy to write a story like this, the information is all out there in public, and you don't really have to understand anything. Politician travels better than the public. But no-one should think that flying business class to Europe is a bunch of jolly good fun. You could have much more fun at taxpayers expense by going to a nice restaurant in Wellington and claiming that off the taxpayer. But $200 here and $200 there isn't quite as obvious a story as $10,000 on airfares.

Both are lazy stories. The real scandals, the real waste of millions of dollars are hidden, not in corruption which is easy to understand, but in bad decisions about government policy (like this one for example). But you have to do some digging and thinking and investigation to find out where millions of dollars are being wasted.

In much the same way as Duncan Garner appears to be doing his job as a journalist by exposing the easy stories Chris Carter appears to be doing his job as Labour's Foreign Affairs spokesman by going overseas. What could advance foreign affairs more? Except that once you've gotten over the jetlag is there really much to be gained by meeting some foreign officials? Not really, not for an opposition which is trying and not always succeeding at being an effective critic of the government.

The big challenge for Labour in opposition is not to know more about foreign affairs and be able to say you've met obscure foreigners, but to come up with some effective criticisms of the government, and some alternative policies. You can do that just as well, better, sitting on a chair in Wellington or Waiheke reading books and newspapers, and thinking a bit. Meeting obscure foreigners is great preparation for being in government, but it doesn't help you get out of opposition. Carter's criticism of the government's whaling "strategy" will do far more for Labour than any trip to Europe.

So, two men, Garner and Carter, misdirecting their professional energies into the appearance of doing their job, they are made for each other.

March 8, 2010

I want to give you money!

In Wellington there is a fabulous non-profit bird sanctuary in the valley of an old reservoir. If used to be called the Karori Sanctuary, and now to try and attract more visitors (for whom Karori means nothing) it has renamed itself Zealandia. Like a lot of non-profits it subsists on a mix of government grants, operating income, memberships and donations.

I'm a member. For $66 (for a couple) you get unlimited entry for a year. I probably run in there once a month on average, which works out to $5 a run and the good feeling of supporting a good cause. The other day I had to find the email address of the membership admin person. This was hard enough, go to the Zealandia website, and there's only one contact address (info@zealandia). None of the other standard categories of administrative emails you might find in an organization.

What about membership? It's totally not obvious from the website that you can actually join Zealandia and support it that way. If you look under visiting it does say there is a member price, but that's about the only indication of membership. Perhaps membership is a small enough category of Zealandia's income that they don't want to appear to be asking for money on the front page of their website. But that's a bit strange. If you're an independent non-profit you have to get the money in from all sources. You can't be shy. Go to the home page of any United States non-profit and it's pretty obvious how to join up and support the organization. The non-profit sector is not nearly as developed in New Zealand as in the United States, and it shows in the softly-softly approach to fundraising many of them take.

December 30, 2009

Technological fixes for terror

The response to the Northwest 253 attempted terrorist attack has been interesting. As after 9/11 and the Richard Reid shoe bombing attempts, one of the distinctively American response has been the reach for the technological response.

A common lament has been that if only there had been a body scanner or an explosive puffer, then Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab would not have gotten his flammable underpants onboard. Another lament, one I am more sympathetic to, is that if the data matching was better the existing screening system would have worked. After all, his name was in the big watchlist database, and then Abdulmutallab purchased a one way ticket with cash and showed up without any luggage. But again the lament is that technology will save us. Data matching is just another fallible technology. The fact that this suspect's names matched in some databases alerts us to one aspect of this case that could have been handled better with technology. But the next terrorist might have different names in different databases and elude easy matching. Americans seem to like technological fixes to their problems. In New Zealand the more common response to problems is that the government should do something, pass a law or establish an agency.

The response has also been interesting in that the technology and organization of suspicion that is encapsulated in screening airline passengers is pretty widely accepted by Americans. But the same logic that makes it OK to screen airline passengers also makes it OK to stop drivers to check for drugs or alcohol, install red light or speed cameras, or impose restrictions on gun use. But few of these interventions which would also save lives are politically acceptable in the United States.

December 21, 2009

A tutorial (discussion section) attendance policy that worked (for me)

Tutorials (discussion sections, but referred to as tutorials throughout because it's shorter) are an important part of university education. Done well, students come away knowing and understanding a topic. Also, students make friends in this form of class. This is a non-trivial benefit. Done badly, they are excruciating in their silence and stupidity, and make a Catholic mass seem short. I refer here to discussions in the humanities and social sciences rather than focused problem-set oriented classes in sciences. The format is often that students have read some documents, perhaps a whole book (at graduate level), or some articles or chapters at undergraduate level. Questions about the readings are posed, and discussion is meant to ensue. But that discussion doesn't always happen in practice.

Done well the students get a great deal of benefit from preparing for the tutorial, and then add to that with their peers' contributions and different perspectives. A large part of the success of a good tutorial comes from a critical mass of prepared students who show up. The question is how to motivate good preparation and high attendance, while also respecting that university students are young adults who can make their own good or bad choices about whether to show up or not.

There are many models for how to motivate preparation and attendance. But I was not satisfied with policies I'd used previously. For example, many of my colleagues in New Zealand have a policy of requiring attendance at 8/11 tutorials during a semester. Missing more than 3 tutorials means that students have not met "mandatory course requirements," and are not permitted to complete the class. It's not uncommon in American colleges for 5-20% of the class grade to be for "participation and attendance."

What I tried this year in my second year (sophomore) social history class was the following policy for motivating preparation and attendance. It worked well.

- There were 10 tutorial sessions in the (12 week) semester, and a final week of student presentations in lecture and tutorial time.

- Five of the 10 tutorials (labeled "starred" tutorials) and the week of presentations had penalties for non-attendance

- Attendance was recorded at the starred tutorials by students submitting at least half a page of notes on the week's readings (1-3 journal articles or chapters, 30-60 pages of reading)

- Non-attendance was penalized with the following deductions from the final mark

- 1st missed tutorial/presentation: 4%

- 2nd missed tutorial/presentation: 8%

- 3rd missed tutorial/presentation: 16%

- 4th missed tutorial/presentation: 32% (highly likely fail)

- 5th and subsequent missed tutorial/presentation: 64% (definite fail)

- Students were encouraged to be responsible about letting me know if they could not make a tutorial for a legitimate reason (sickness, other university event clashing), and that if they handed in their notes they would not have marks deducted.

It looks way more complicated than it really was. Since it was a policy that differed from the standard ones in our department (and cognate departments in the humanities and social sciences) there were some questions about it. But the students understood it without any problems.

With this policy, 27 of a class of 31 did not lose any marks. In other words, 90% of the class attended (or demonstrated their preparation if sick or otherwise legitimately absent) for all the tutorials they were responsible for coming to. One student lost 4% and another 8%. Two students failed after missing 4 tutorials.

So, the policy had a very beneficial impact on student attendance. Most students prepared for class by taking more notes than required, and class discussions went very well as a result.

The policy seemed to work well for the following inter-related reasons

- I eliminated the common "mandatory course requirement" of (x-3) out of x tutorials that just permits absences from 3 tutorials. These absences are often concentrated around the deadlines for other classes, and especially at the end of semester. Students are busy and they reasonably prioritize things that are graded, or are fun. Wishing they loved learning more, and exhorting them to do so, just leads to disappointment.

- The sharp break in the "mandatory course requirements" approach between the penalties for missing 3 and missing 4 tutorials is unfair, and not well designed to motivate consistent preparation and attendance.

- The severe level of the penalties for frequent absences got students' attention, as it meant failing

- The policy did not require me to grade participation per se. The burden on me in implementing the scheme was minimal (less than 5 minutes per class to scan the notes that were submitted and record who didn't submit notes).

- A realistically small level of notes submitted for attendance (half page) was meant to achieve two goals

- It was meant to be, and was, seen as a realistic amount for students to achieve.

- I also encouraged the students to try and be concise in their note-taking, developing the skills of summarizing an article in a few lines -- that sometimes less is better for them. It was much nicer being able to tell students that they had somewhat over-prepared and discuss how they could do less work (but more effective!) next time.

- I did not try to compel perfect attendance, but designated some tutorials as more important than others. 6 weeks in which attendance was rewarded seemed to strike the right balance between encouraging work on this class, and recognizing that there can't be something due every week. The "starred" tutorials were mostly in alternating weeks.

- In the alternate weeks I ran practical workshops to help students with their research for the class. These were sometimes structured (worksheets on various aspects of the research), and sometimes an open computer lab. Clearly, not every class would need computer labs. The general idea was to do a more practical session where the success of the session did not rely as much on student preparation or attendance.

- In practice (this being the winter of the swine flu) I was understanding of student absences, when notes were submitted. Students seemed to view the policy as reasonable. The policy did the work of motivating students to prepare. I did not have to exhort students to do the reading and prepare for class because there was an objective penalty for not doing it. This freed up my emotional energy for more important things in the class.

The policy seemed to have a positive effect on classroom relationships, as well as motivating preparation and attendance. The awful tutorials where people attend without having done the reading, and the discussion proceeds slowly until the instructor realizes students haven't done the reading. The instructor then gets cranky at the students for not preparing for the class, and the relationship between students and instructor suffers.

All in all this was a low-workload way of motivating student preparation and attendance, and it seemed to improve student outcomes. By making the penalties for not preparing and attending explicit I respected students' abilities to make their own decisions about their time. Attendance was not compulsory, but it was valued.

By penalizing non-attendance and preparation rather than grading participation and attendance I did not have to grade students' contributions to discussion. This meant the discussion atmosphere was relaxed, because students who attended had prepared, but knew they weren't being evaluated for what they said and did once in class.

The details of the policy would vary in other classes, but the key features I would replicate are

- Preparation and attendance at about half the tutorials was valued

- Other tutorials were less dependent on student preparation/attendance

- Attendance was measured by a reasonable amount of non-graded work that nearly every student was able to regularly exceed

- Penalties for non-preparation and attendance were small at first 'miss', but increasing.

Finally, I must gratefully acknowledge my colleague, Alexander Maxwell, who suggested aspects of this to me, but disagrees with some of my adaptations.

December 2, 2009

Predicting the future is hard

Now that Obama has given his big speech on Afghanistan we get the predictable debate between people who think that the June 2011 deadline is arbitrary and signals to the enemy how long they need to wait for America to leave, and those who think that's too long.

Really I sympathize with the idea that withdrawing from Afghanistan should be "conditions based" but there are few areas of human activity where open-ended commitments are a good idea (marriage is somewhat of an exception, but that's for another discussion).

People respond to deadlines. Although, as a professor, I get a regular stream of amusing excuses for why students haven't met deadlines, the striking thing is that most students meet most of their deadlines. Obviously there's a huge gap between a student assignment and the "world peace" scale problem we have in Afghanistan. The time it should take student assignments to be done is predictable; they've been done before and they are quite small. Afghanistan is a large problem we haven't met before.

Quite obviously the July 2011 deadline for U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan is arbitrary. There is no previous Afghan war the deadline can be based on.

Deadlines, however arbitrary, concentrate the minds of the people affected by them. An open-ended commitment to war is good for defense contractors, but bad for everyone else, including the Afghans. If the U.S. said it was staying for some unspecified time, and withdrawing based on some concept of progress there would be fewer incentives for Afghans to take over their own security situation. The trick is that in situations like this—complex and unique—there has to be some flexibility in the deadline. Who knows if 18 months is long enough? The future is unpredictable. So it's no surprise that the morning after the speech the White House appears to be saying two things, there is a timeline for withdrawal, and that the timeline is flexible.

Sticking rigidly to a timeline or having no timeline at all are not strategies that work in any other area of 'complex' human activity. The timeline that can be altered is the only realistic way forward.

September 1, 2009

Laws and language

The creativity of the Wanganui gangs protest against gang patch laws was amusing. Like the anti-smacking law we have a nice demonstration here of the ultimate ineffectiveness of laws, because language is not complete.

You can ban gang patches, but it turns out that within a day of the law going into effect it turns out that what Michael Laws really needed to ban was "visual demonstration of affiliation to a gang." Laws (on the statute book) need to be specific if they are not to be a license for police harassment. But when laws are written to address specific behavior, the targeted groups change their behavior.

Was it really the patches that intimidated the residents of Wanganui? Or a group of Maori men gathering in a public place? No one wants to admit they are intimidated by Maori men gathering in public, so instead we get the symbolic politics of banning gang patches.

And what is the line between a smack and a whack? How would you write a law that defined that? A certain amount of pressure, perhaps you could be allowed to swing your open-faced hand at your child at no more than x metres per second. The absurdity is obvious. How would you enforce that with no witnesses and no measurements? Thus, the choice between ruling smacking in or out of the law. There is no way to codify what a "reasonable" smack is. Similarly there's no way to anticipate what will signify gang affiliation, and write a law outlawing it all.

The futility of our language now against future behavior doesn't mean we shouldn't have laws about social behavior, but we should be modest about what they can achieve.

August 5, 2009

Wankers in the Post Office and Fed Ex

When I read Paul Krugman's note about critiques of government services in America being a bit detached from reality I thought "sure, great point in theory, pity you illustrated it with the Post Office." Now, Krugman says "Maybe I'm living a sheltered life here in central New Jersey," and perhaps it's an metropolitan versus small-town thing, but the Post Office is not a good advertisement for the Federal Government providing customer service.

It has struck me that all of the Americans who have visited us in New Zealand this year have commented on how nice the staff are at the post office. One of the great things about Australasia is that small retail post offices are contracted out to book stores and newsagents, a class of the retailing industry where I think you tend to get decent service anyway (at least in my travels in the English-speaking world).

A few years back I recall the USPS proposed contracting out post offices to retailers, but stopped because it would give those firms an unfair advantage. Huh? If firms perceive there's an advantage in also providing postal services they could bid for the local rights to do it. Though it's quite possible that the rights might be worth less than the costs, and USPS would be paying them for it. Contracting out parts of the retail postal service might have improved the terrible location of many central city American post offices (not in central retail districts, not in malls; you have to drive them often). Probably rightly the USPS doesn't want to pay central city retail rents for space they are using for sorting and other operational needs. But there's no need that the selling stamps etc couldn't be done at more retail outlets.

It could hardly be worse than the experience at USPS. Many Americans probably aren't aware of this, but sending an international parcel is something you need to put on your calendar it takes so long. The absurdly duplicative customs declaration forms, the total confusion of the stupid staff about where some foreign countries are (you work in a post office, you should know these things!), it literally drives me to Fed Ex some of the time.

At Fed Ex, as Nate Silver points out, the experience isn't much better. The staff are not so much surly like at USPS as disinterested, young, and not very well-trained. The USPS staff more often give the impression of knowing the rules and processes, but not caring to use them in your service.

So I've had lots of banal, lousy customer service at the USPS. But my single best story comes from a 1am trip to FedEx Kinkos to get copies done for a work presentation. In the hour I spent trying to get the printer to print properly (the totally disinterested 1am clerk had no ability to fix anything, but thankfully didn't charge me for all the paper wasted in trying to get the right printing done), I shared the computer space with a morbidly obese man who was talking to himself and masturbating through his shorts while surfing cherryblossoms.com (warning: obviously NSFW unless you're in academia and this would be research into multimedia).

It would have completed the picture of the ugly side of American life if he had been eating McDonalds and there had been an armed robbery (1am - 2am, remember), but sadly that was the whole of the story.

The Post Office isn't open at 1am for people like this, so I suppose that makes FedEx just slightly better ...

August 3, 2009

Honoring women by putting them last

This is the form on the Susan G. Komen website where, if you're giving a donation, you have to specify a title. There's several odd things about it. First up, where are the imperial titles like Sir and Dame? Do they not want the aristocracy to give money? What about religious titles? What if you were both Doctors? Or Professors? A badly coded list.

But the thing that really got me, given that this is an organization dedicated to a disease that mostly affects women, is that if you're putting two titles down, the woman's title comes last. Yes, yes, I know, that's convention, Emily Post probably says this is the way to do it, but it doesn't make it right. If any organization should put women first, it should be this one.

June 24, 2009

The quick and the stupid? Or the clever and the slow?

Do students who finish tests quickly score better or worse? This is an interesting question for educators. For good reason there is an implicit bias towards the idea that if it's done quicker, for the same grade/mark, it's better. Yet there is a time and a place for being quick, and a time and a place for being more considered about your answers.

I had an opportunity to do some "research" on this recently. A colleague and I gave an end-of-semester test to 91 100-level (freshman) students in our American history survey. Students had up to 50 minutes to answer 70 questions, with a range of formats including short answer, multiple choice, and identifications. From our mid-semester test we had a fair idea that the median time to completion would be about 40 minutes. Our goal was a test where the challenge was the content, not rushing to finish.

Because both my colleague and I were heading out-of-town shortly after the test, the students answered the test on a single side of paper each. We collected the paper in a box at the end, and then ran all 91 tests through the scanner. This numbered the pages automatically, and all I had to do after we'd marked the tests was rank the scores on the test in Stata (when you have a hammer, everything looks like a nail).

My prior belief before seeing the data was that there might be a U-shaped relationship between the ranks of completion and handing in. Students who did well would either be quick or slow, tortoises or hares winning the race in different ways. Of course, one could also have the prior belief that an inverse U-shaped relationship would hold for the students who did poorly. Some would complete quickly, either realising they didn't know anything or just rushing through the test to go [insert prejudice about under-motivated students here], while others would do poorly through failing to complete all the questions.

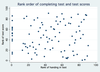

By way of explanation in interpreting the graph, a lower rank on completion means the student waited longer to hand in their test. The vertical line on the left side of the graph is the 12 students who all handed in their tests at the very end when we called "time". A lower rank on the test score is a worse score.

What appears to happen is that there is no discernible relationship between when students handed in their test, and the mark they received. A moving average gives us a slightly different perspective.

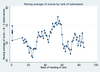

Recall that a lower rank of handing in the test means students waited longer, and note that the overall mean for the test was a score of 51.3 out of 75 (68.4%, a B on our grade scale).

A moving average forward and back 5 observations shows how student performance varied with submission. The 12 students who waited right until the end to submit had a slightly higher average than the grand mean for the class, but nothing that approached statistical significance. There isn't strong evidence that the slower students are more careful and thus scoring higher.

The average rises towards the middle of the order of tests being submitted, and then falls back towards the overall mean. But note what this last fact shows, the students who finish the test earliest are not doing any worse than average. At least in this class on this test, the students who finished early were not rushing to slack off.

In conclusion, there is some relationship between time to complete the test and scores, but it is not an obvious one.

Nixon is making sense

On NPR yesterday there was a discussion about Iran. To give balance to the programme, the guests were from the right wing American Enterprise Institute, and the right wing Nixon Institute.

What was most interesting was just that, the Nixon Institute. Has Nixon's reputation really been rehabilitated to the point where it's an acceptable name for a public policy institute? Apparently so.

What was then surprising was that the Nixon Institute guest actually did provide balance and lucidity on the issue, saying that America shouldn't try to intervene in the Iranian electoral dispute.